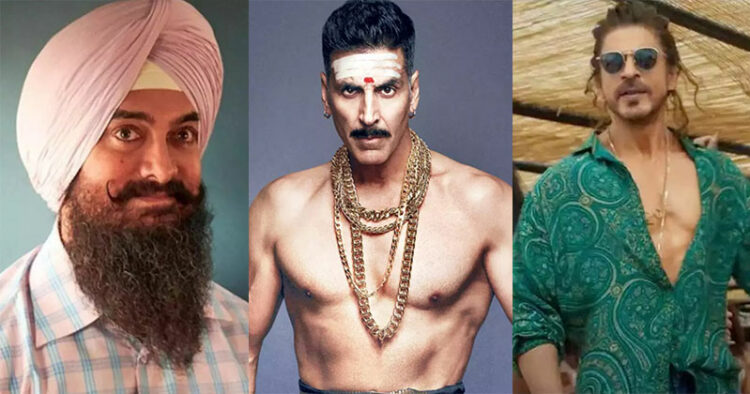

I came across a very interesting thread on Twitter that tried to extol the commendable traits in Abhishek Sharma’s recent dud Ram Setu, starring apart from the erstwhile bankable Akshay Kumar, Telugu cinema’s noteworthy actor Satyadev. And Jacqueline Fernandez was arm candy, as usual. The original tweet complained that the film didn’t do well despite being a Hindu-proud narrative. This was a wry stinker directed at the recent boycott calls singularly aimed at all Bollywood products. The writer of the tweet sarcastically tried to discuss that the movement is so pervasive that it is not sparing even those films that are either nationalistic, proudly flaunting Hindu iconography or devoid of rabid defamation targeted at Hindu culture, beliefs and traditions.

Following the thread carefully though, would reveal the real reason for the film’s failure and which put the initial claims of the tweet author at rest. Technically flawed and not exactly great cinema, it was the flaccid script and poor execution that failed to impress the audience. Satyadev was the only saving grace, said those who did watch the work. One remark summed the mood of the Indian audience with respect to the Bollywood commercial graph.

With two per cent people (of the entire movie-going tribe in India who watch Hindi cinema) involved in the boycott Bollywood calls in an urban chatroom, the film industry cannot really blame that percentage to be the real hand behind the alienation. It is high time filmmakers in Maharashtra’s tinsel town realise that it is bad content generation that is bogging them down.

The masses have a severe disconnect now from jaded stars, lacklustre scripts, glorification of drugs, sex and nudity, horrible performances, nepotistic outlooks, talentless clubs and coteries and degraded music. If devolution had been the Bollywood signet for quite a while, what they are churning out regularly now is similar to a flogged old horse. Why would any smart person even want to ride that!

If Indian film lovers have boycotted Hindi cinema quite passionately (in 2022, no production could break even except for superhits The Kashmir Files and Drishyam 2), what triggered them to do so after decades of faithful patronage? No matter how much industry biggies slam rising intolerance and aversion towards artistic license, can trade pundits deny that numbers dwindled because of the degenerative matter directors, storytellers and producers have come up with for years on end!

Ironically though, while the Hindi film industry sulks about their work not being appreciated enough and facing resistance, the powers-that-be aren’t yet in the mood to introspect about what brought them to the juncture of repeated failures. Rather, what powered the people’s movement to shun Bollywood that has the industry grovelling. If Indian film lovers have boycotted Hindi cinema quite passionately (in 2022, no production could break even except for superhits The Kashmir Files and Bhool Bhulaiyya 2), what triggered them to do so after decades of faithful patronage? No matter how much industry biggies slam rising intolerance and aversion towards artistic license, can trade pundits deny that numbers dwindled because of the degenerative matter directors, storytellers and producers have come up with for years on end!

Finding a connect with better work

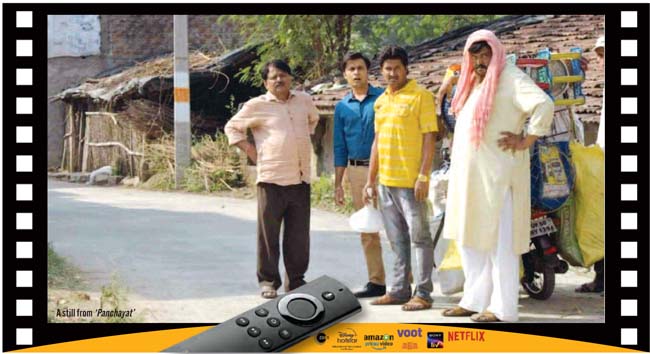

The urban audience, for entertainment, doesn’t have to rely on substandard fare dished out by the Hindi film industry anymore, courtesy the brilliant craft being created for OTT platforms. Sleeper hits such as Jaadugar (starring Jitendra Kumar) and heartwarming series like Panchayat, Gullak, Ghar Waapsi and the brave Avrodh: The Seige Within have proved that you don’t need any Khans, Kapoors and Bhatts to deliver a hit. In fact, smaller productions have dared to scratch the surface of a variety of topics, given scope to better actors and tackled important and relevant issues way more judiciously than Bollywood writers ever have. The detailing and earnestness put into some small films and series have ensured the audience praised them repeatedly. The retentive value is one of the primal forces that worked towards consolidating this connection. Even if sensitive matters were being spoken about, there was objectivity involved in telling them. This balance in narration ensured hearty applause by those who lapped up these works and endorsed them openly. Also, the freshness of stories, scripts, faces, music and the very feeling of ‘we have been there’ or ‘this could be us’ functioned. Now, when was the last time you saw told yourself that while watching a commercial Hindi movie from the Bollywood stable?

A discordant note of relevance and relatability

Independent filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri, who courted not just success with The Kashmir Files in 2022 (his Buddha in a Traffic Jam and The Tashkent Files were sleeper hits) but also bore the brunt of vehement attacks to silence his quest to project the bare truth about the Kashmiri Hindu genocide and exodus in 1990 opines, “No film made till date on this subject dared to project the reality of Kashmir. While some whitewashed facts, some distorted them even as the world was fed with lies about what had happened. This was classic Bollywood and its big directors who were busy pandering to the Islamists to keep the cauldron of propaganda boiling. The criticism the film faced was not just misplaced, but it also exposed the insecurity the entire industry felt on being exposed for their sham. The film was boycotted by the famous in Bollywood for obvious reasons but the audience made it roar because they related to it. It became a mirror they earned to show the world after much struggle about what the Hindus in Kashmir faced and how the political powers let them down time and again.”

The criteria of relevance played a significant role in the way the masses sidelined Bollywood films. For instance, Shakun Batra’s Gehraiyaan starring Deepika Padukone and Siddhant Chaturvedi. While the makers might have banked on the very urban storyline to grab the attention of the plex audience, the negative reaction explained that people were fed up with the normalising of drugs, depression and illicit relationships amongst the youth through such dramas. Also, the jaded plots, lack of context, repetitive subjects and unnecessary nudity. Maybe that’s why Zoya Akhtar’s The Archies (to be out in 2023), which stars a battery of celeb kids including Khushi Kapoor and Suhana Khan, has already received brickbats for being thoroughly un-Indian and fake, even as netizens have pointed out how such flaky films set wrong narratives amongst impressionable youth. Clearly, the thread of reality runs dry in big, bad Bollywood.

Comparisons with other Indian cinema

Even though Hindi cinema has regularly lifted scripts from the southern film industries, they failed to evolve the way the latter did. Let me explain. It’s not that the Malayalam or Tamil film industries don’t serve wrong or distorted narratives or that their movies are completely devoid of propaganda. Definitely not! But, filmmakers working there garb their anti-Hindu diatribe cleverly with fascinating technicalities. In fact, they have always done it with a such artistic flourish that the general masses could hardly ever catch the subliminal messaging. This has been happening for years, and it continues till date. The rabid Communist agendas peddled through Malayalam cinema is evident and ingrained. The anti-Brahminical threads running in Tamil cinema is a constant. For instance, the recently successful Suzhal – The Vortex is a series focused on exemplary cinematic brilliance with a smattering of defamations against indigenous Hindu traditions and rituals practiced during the Mayana Kollai festival in the villages of Tamil Nadu. But, any cinema lover would be willing to sift through the liberal dosage of venom and concentrate on the cinematography, story, acting and overall mood.

Filmmakers such as Vetrimaran, Girish Karnad and so on have always laced their work with extreme anti-Brahmin and Hindu jibes so that purveyors of their cinema are bound to see the Hindu society as casteist and discriminatory without exploring causality. Mani Rathnam’s Leftist eye has done the same too, while his wife Suhasini, ensured the imbalance is maintained in her award-winning works like Indira. When the Indian audience was applauding Nayakan as a watershed moment in the journey of Tamil cinema due to the flair with which a real life goon’s life story was presented, I doubt anyone complained that this was the abject glorification of crime and criminals. Similarly, when Kamal Haasan’s Anbe Shivam was serving an acutely Communist dialogue to his audience, they concentrated on the beautifully stitched narrative, no matter how lopsided, and made the director and actor laugh to the bank.

So, the heart of the matter is, for a large segment of the audience, finesse of the work matters. Because the minds of the masses are yet to be that trained to figure out how moviemakers are playing with them. Yes, as soft powers, cinema holds a firm grip on consciousness, but often, when packaged well, the toxicity is cleverly garbed. Bollywood is yet to learn this trick that involves class and high aesthetics, that is resulting in fobbing off the general audience. The maximum they can do is titillate with trophy tropes dressed in designer bikinis, amplify tasteless same-sex love-making scenes to generate hoopla, sexualise synthetic abs of an almost sixty-year-old ‘star’, justify terrorism and narcotics, serve bawdy, crass humour and call it witty, stuff item numbers to bolster barely there scripts or hope to break the box office jinx with deplorable nonsense like Cirkus that no one even bothers to reckon now!

Sharmi Adhikary is a senior lifestyle journalist and columnist with a yen for exploring interesting concepts in fashion, culture and cinema.

Comments