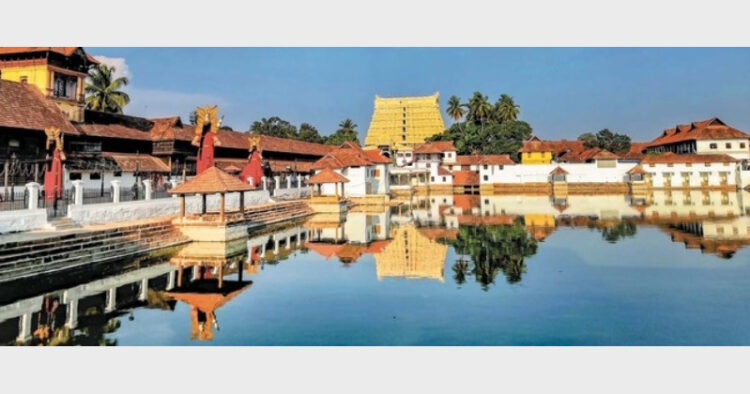

After a decade, I have finally returned the trusteeship of this fabulously wealthy temple of Lord Vishnu to the ruling family of Travancore.

Devotees of Kerala’s historic Sree Padmanabhaswamy temple rejoiced at the July 13, 2020, ruling of India’s Supreme Court upholding the rights of the royal family of Travancore to administer the wealthy temple.

The two-judge bench of Justice U. U. Lalit and Justice Indu Malhotra reinstated the rights of the royal family as the shebaits (a person who serves and supports the established Deity), overruling a 2011 judgment of the Kerala high court. “We hold that the death of Sree Chithira Tirunal Balarama Varma (the last maharajah of Travancore) would not in any way affect the shebaitship of the temple held by the royal family of Travancore,” the court stated.

The Kerala High Court had directed in 2011 that the state government take control of the management and assets of the temple, immediately divesting the royal family of their hereditary rights to administer the temple. The family appealed to the Supreme Court against this judgment.

By May of that year, the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple had caught the world’s attention by reports on the extensive wealth preserved in the underground vaults (kallaras) for centuries. Soon social media exploded with exaggerations, including fake pictures of the treasures (see my 2012 article: bit.ly/padmanabhaswamy).

According to Uma Maheswari, author of 33 books on the history of the state and this temple and regarded as the world’s most authoritative expert on Travancore history, “The wealth found in the kallaras are offerings made by the royal family over centuries. The description of the ornaments, the weight, length, type, number of gems used, money, etc.—every detail is exhaustively documented in the Mathilakom records. The royal family have inherited divinity and their offerings to Sree Padmanabhaswamy haven’t stopped. They don’t make it public.”

The 2011 Vault Opening

In 2011, India’s Supreme Court appointed a seven-member committee, which ordered the opening of all the temple’s kallaras, some of which had remained sealed for centuries. Devotees and Hindu organizations vehemently opposed this judicial interference in their religious beliefs and tradition, but five out of the six vaults were opened. When vault A was opened, a symbol of a hooded snake on the back wall of vault B could be seen. It is believed the symbol indicates forbidden territory, and opening it would bring widespread misfortune. After strenuous protests, the contentious vault B was left untouched.

When the five vaults were opened, rumors of the wealth flowed freely. Overzealous committee members described publicly what was found without considering the ensuing security risks. But no doubt the value is in the billions of dollars.

In 2012, following hiccups in administration and communication with the court-appointed committees, the Supreme Court appointed Gopal Subramaniam, a lawyer, as an amicus curiae (Latin for “friend of the court”). At that time they also appointed an executive officer to run the temple. He, unfortunately, did not adhere to the temple’s centuries-old rituals and practices. “He enjoyed the confidence of the amicus curiae and started making changes to the structure and rituals,” states K. P. Madhusoodhanan, General Secretary of the Fort Area Residents Consortium (FARC), who fought against these violations.

On condition of anonymity, a temple official stated, “The amicus curiae was insistent on having B vault opened, saying he had a vision of a Sri Chakra inside which should be placed in the temple sanctum. Claiming divine direction, he wanted to enter the sanctum sanctorum, an area that has never been entered into by anyone other than the priests and certain pontiffs.”

Other changes were demanded with regard to the central sanctum. Mandapas (open pillared shrines) adjacent to the temple tank were demolished. An attempt to install an automated steel door below the main gopuram caused structural damage (and the door never worked). Contrary to custom, pesticides were used in the adjoining Sree Narasimha Temple. Without reason, the custom of blending saffron with the sandalwood paste offered to the Deities was discontinued.

One of the most significant rituals associated with the royal family—the offering of sandal paste upon the birth star of the previous rulers—was stopped. The obvious intent was to remove any link between the royals and the temple. The temple’s requirement that devotees come in traditional attire was relaxed—a decision ultimately reversed by the Kerala high court. The amicus curiae also requested a change to the ritual 3:30 am waking of the Deity, which had always been done by blowing a single conch. He wanted to do it with nadaswaram horns and two dozen other instruments—a combination capable of overloading a decibel meter.

Behind the Takeover

Hindus in India have been protesting for decades against governmental interference and takeover of temples—while the government leaves churches and mosques untouched. A takeover of the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple—beyond its effects on the temple, devotees, and royal family—loomed as one more glaring injustice to the Hindu faith.

Following Independence—when princely states were merged with the Union of India—the then Maharaja of Travancore, Chittira Tirunal, was given the opportunity to retain properties of his choice. In unequivocal terms, he sought that the administration of Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple be continued in trust with the ruler of Travancore. This was part of the covenant signed while handing over the princely state of Travancore (most of modern-day Kerala). The Maharaja was assured that the temple administration would remain with the royal family.

The covenant of the merger between the Indian Union and the Maharaja hence protects the sublime relationship between the Travancore royal family and the temple.

According to advocate M. K. S. Menon, one of the teams guiding the case, “While signing the covenant, Maharaja Chittira Tirunal was given the choice to retain properties of his choice. The Maharaja wanted the temple to remain with the royal family since it is the centrifugal force of their very existence. Chittira Tirunal stated that he could not sign the covenant since he was not the sovereign. Sree Padmanabhaswamy is. So the Maharaja signed as the representative of Sree Padmanabhaswamy.”

Misinterpreting the term ruler for sovereign (in the sense of “political leader”), the Kerala high court decided that the government must take over the temple. “The senior-most member of the Travancore royal family was not the ruler in a political sense. It was a status he held. The Travancore Cochin Religious Institutions Act 1950 endorses the rights of the ‘Ruler’ in the administration of the temple. When this act came into force, the government retained the word ruler, though rulership [as a political power] was abolished post-Independence. This was accepted by the state of Kerala, too, when it was formed in 1956,” states advocate Menon. In other words, the “Ruler” referenced in the 1950 Act was the Maharaja, not the head of the Kerala state government. It was a subtle but critical point.

Dark Days of Litigation

For generations, the royal family have completely submitted themselves to the Deity, dedicating everything they have to Him. They live for Sree Padmanabhaswamy and lead a life of piety and frugality. Unlike some other princely families in India, they have eschewed political involvement and extravagant lifestyle.

Ratings-hungry media circulated false and sensationalized reports accusing the royal family of misappropriation of wealth. The amicus curiae report was replete with stinging accusations against the late Maharaja Uthradhom Tirunal, who at past ninety years, with a leg injury, would still walk three kilometers barefoot to the beach during the Aarat festival, as he led the Deity parade carrying a 17th-century ceremonial sword (photo page 31 bottom). Insinuations of theft and even murder were implied.

Since the matter was sub-judice, the royal family could not defend themselves in public against the smear campaign. When I had asked the Maharaja, the late Uthradhom Tirunal, how he felt about T. P Sundararajan dragging the royal family to court with false allegations, he simply stated, “Keshava [Vishnu] can come in many forms.”

Madhusoodhanan of the FARC was less forgiving: “Their intentions were shrouded in viciousness, it was to taint the royal family, divest them from temple administration and change all the traditional aspects of the temple. People were manipulated to turn against the royal family. The amicus curiae’s reports were given credence, since he was appointed by the apex court. Public opinion was built towards separating the royal family from the temple. This was the ulterior motive and very disturbing. We decided to fight this injustice; the royal family had to be supported and the temple had to be saved”.

People for Dharma worked with FARC to prevent a government takeover of the temple. “The State is a tenant which does not vacate once it enters a temple’s framework,” asserted advocate Sai Deepak of People for Dharma in his written submission to the Supreme Court.

“We sought that rituals and traditions must not be tampered with, and that the amicus curiae report must be rejected by the court,” explains Madhusoodhanan.

The royal family’s Princess Ashwathi Tirunal Gouri Lakshmi Bayi took a very active role in the case. “I was present in the court for every hearing, spending long hours at the advocate’s office, traveling late at night, waiting all day in the dusty corridors on the hard benches for the case to be called, without any food through the day.… I remember how I stayed up all night making notes for the case the next day and collapsed in front of Sree Padmanabhaswamy’s photo at 6:30 in the morning and wept and wept and wept.

“Once when our case came up for hearing, a journalist sitting beside me in the court said, ‘Oh, they are the people who stole from the temple.’ Another journalist who recognized me nudged her. The lady looked at me and said, ‘Sorry, I simply said it.’ I told her, ‘For you it may be “simply,” but for us it’s a big blow. It’s people like you who create the problem, you don’t know the truth do you?’ ”

Eminent jurist William Blackstone once propounded that it is better that ten guilty persons escape than one innocent suffer. But in this case, slanted media, rumors and sensationalism were letting the guilty escape while the innocent suffered.

Advocate Menon one among a team of senior advocates, faced a tough task to win the case while enduring the challenges of hierarchy in advocates. “The emotional trauma that they went through—every second they were in pain,” he says. “I wanted only one thing, justice must be done.”

The Supreme Court Battle

Ultimately, the priests and devotees had enough. Advocate Menon approached the Supreme Court for the removal of the executive officer. “He was called to the court, questioned and asked to resign,” recalls advocate Menon, one of the few positive signs during this trying period.

The 2012 case was fought with historical documents on both sides. Countering false reports denigrating the royal family were the temple’s own records, called the Mathilakom collection and numbering three million palm leaves. They document minute procedural details relating to the functioning of the temple and narration of events over centuries. “These records also prove that the history of Travancore, the royal family and history of Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple are interlinked. The temple is their identity,” says Uma Maheshwari.

When news broke in July of 2020 that the Supreme Court judgment was imminent, temples across the country performed special pujas praying for the victory of the royal family, including by the Dikshitar priests of the Chidambaram Nataraja temple. Special abhishekas were performed at the Kashi Vishwanatha Temple in Banaras. Innumerable devotees and well-wishers engaged in prayers, many reading the Srimad Bhagavatam.

Victory and Aftermath

In the Supreme Court’s final judgment (see below), temple control was completely returned to the purview of the royal family. The reports of the amicus curiae and auditor Vinod Rai were not considered for the final order. It was the end of an unsavory and harrowing decade-long litigation during which the royal family were made bystanders, helplessly witnessing administrative failures and the flouting of temple traditions.

The battle drained them in more ways than one. The innumerable trips to New Delhi and lawyers’ fees, among other costs, had financial implications. During the litigation, while the temple was run by the court-appointed committee, the royal family through the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple Trust continued to shoulder all temple expenditures. According to local sources, us$1.1 million was unnecessarily spent by the ad hoc administration on installation of a number of gadgets, unauthorized renovation work around the temple complex, appointment of unnecessary staff, multi fold increase in salaries and other excessive spending. Monthly expenditure rose to $157,000, against an income of $68,000. Now, with the new administrative and advisory committees in place and the royal family regaining the temple rights, the bitter past and mismanagement can be put behind.

“On the day of the verdict,” recalls Princess Aswathi Tirunal, “the entire family along with our staff were in front of the TV that morning, and we saw a flash news that the Travancore royal family has won the Sree Padmanabhaswamy Temple case. We were grateful to all the known and unknown people who have stood by us, prayed for us, grieved with us, worried for us and fought for us. It’s a debt we can never repay.”

The royal family released a joint statement, concluding: “We regard today’s Supreme Court verdict as a blessing from Sree Padmanabha Swamy, not just for the family, but for all His devotees. We pray for his continued benevolence on all humanity to keep us all safe and well.”

What the Court Finally Ordered

Restoring the rights of the temple to the royal family for posterity, with the head of the royal family as the Trustee having the final say, the verdict also prescribed the formation of an Advisory Committe and an Administrative Committee, of which all members must be Hindus.

The Administrative Committee consists of five members. The first is the district judge of Thiruvananthapuram, who serves as chairperson. The second is the chief priest of the temple. The remaining three are nominated one each by the royal trustee, the government of Kerala and the Minister of Culture of the government of India.

The Administrative Committee is authorized to take a fresh look at the current standard operating procedures with respect to all aspects of the administration and operation of the temple. In all matters spiritual and religious, or concerning rituals, the views of the chief priest will be binding on the committee.

The Advisory Committee shall consist of 1) a retired judge of the High Court of Kerala as chairperson, 2) an eminent person to be nominated by the royal trustee, and 3) a reputed chartered accountant nominated by the chairperson in consultation with the royal trustee.

The court ordered that these two committees also look after a slew of other tasks, including preserving all treasures and properties endowed to the Deity and belonging to the temple; protecting all tenanted properties, and taking appropriate measures to ensure reasonable financial returns from such tenanted properties; as well as ensuring that all rituals and religious practices are performed in accordance with the instructions and guidance of the chief priest and according to custom and traditions.

The Administrative Committee can only with the prior approval of the royal trustee take a decision on the following matters: any expense item exceeding us$20,475 per month, any one-time expense of more than $136,500, any major renovation or expansion of the temple, any changes in established operating procedures, and any fundamental changes in the character of the Temple that would affect the religious sentiments of the devotees.

The author has been a journalist for over three decades. She writes on current affairs, policy matters, constitutional and legal issues, heritage, and culture. She wrote and directed the documentary, “At the Altar of India’s Freedom—The INA Veterans of Malaysia,” produced by the Indian High Commission in Malaysia. She holds degrees in journalism and law.

Comments