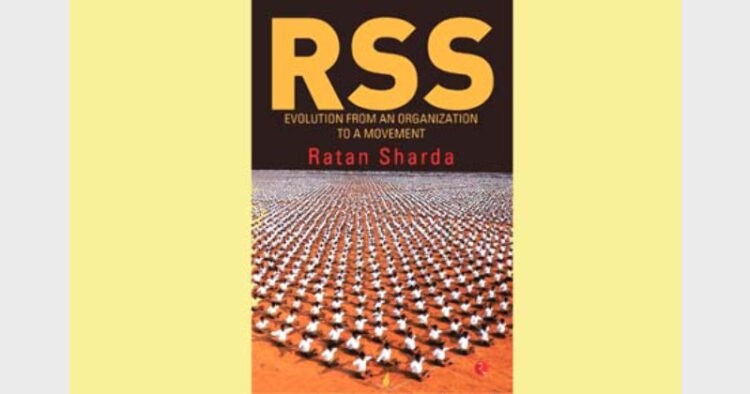

RSS: Evolution from an Organisation to a Movement; Rupa Publications, Pp 408, Rs 500.00

This book by Dr Ratan Sharda is an ideal successor to his bestseller “RSS 360 – Demystifying Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.” “RSS: Evolution from an Organisation to a Movement”, released during the Covid-19 dominated lockdown, did not create the expected ripples for the very reason. While "RSS360" is like an introduction to RSS – its philosophy, its working, and its manifestation responding to many oft-repeated criticism and allegations too; this book is a wonderful walk through of 96 years of history of RSS. Tracing the evolution from an isolated small organisation to a movement that has become part of the society as envisaged by its founder Dr KB Hedgewar, through the lives of successive Sarsanghchalaks, is a novel approach chosen by the author.

For a casual observer, RSS is a staid orthodox organisation that is stuck in some time war. However, the author presents a convincing argument about its dynamic nature and ability to adapt to the changing social environment. The writer reminds the readers of the four socio-political groups that rose a century back in Bharat – Congress, Socialists, Communists and RSS. Only RSS has kept expanding and seen an evolutionary growth while the other three have lost steam. The reason is the inability of others to adapt to the environment.

The author brings out many interesting facets of this organisation and its leadership which outsiders generally fail to perceive. For example, all the Sarsanghchalaks have common qualities like very high IQ, EQ and SQ, strong memory, simple lifestyle and sthitpradnya nature or equanimity. They are as comfortable with the common people as with the elite opinion-makers. Most of them know many languages. An amusing similarity is that except Balasaheb Deoras, all other RSS heads are from the science stream. Despite these similarities, all of them have distinct personalities, and they put their stamp on the organisational history of the RSS. A person doesn't rise inside the organisation due to personal equations as it is a goal-oriented organisation and not personality- bused. Ability to take along the people and find solutions to situations as they arise filters out people gradually, and one rises in the ranks through meetings and actions on the field.

Ratan Sharda explains that Sarsanghchalak is not the executive head, but he is the guide and philosopher of the organisation. He is also the face of the organisation. His word carries weight within and outside the organisation. However, he takes decisions in consultation with his team and is open to words of any swayamsevak or volunteer and active workers (karyakartas) at any level. With this rooted approach, his ideas give direction to the RSS. Thus, each RSS chief has left behind a permanent legacy mark in the evolutionary process. The writer is able to bring out the distinctive flavour of each of the Sarsanghchalak’s personalities through the brief life sketches he draws. His narration is interspersed with interesting and heart-warming stories, thus making it an enjoyable read and seeing the leaders’ humane side. These stories highlight the changes that happened during different periods. At the end of each chapter, he summarises the work of each Sarsanghchalak as the supreme leader of the organisation and changes he could bring out during his tenure that sees its progress to the next stage.

Some chapters in the book are fascinating insights of the author about RSS that help readers understand the evolution of the organisation better and its probable future path of expansion. For example, he highlights that many organisations have come up for the renaissance of Hindu society since the 19th century. However, all of them had a religious base that assured the follower/member of spiritual enrichment and showed the path to moksha or nirvana. They depended heavily on the personality of their founders. RSS is the only organisation that kept its goals distinctly material. It demands a spiritual dedication, a mindset of a karma yogi, but does not promise nirvana. There is no spiritual guru in the organisation. Motherland is the presiding deity in a swayamsevak’s life, and Bhagwa Dhwaj (saffron flag) is the guru. The goal, as spelt out in the daily prayer, is supreme prosperity (Param Vaibhav). Except for Vishva Hindu Parishad, inspired by RSS, no other organisation has religious objectives.

All other organisations work for social and material upliftment and bringing social harmony by influencing reformist approaches to Hindu traditions and nurturing Bharatiya knowledge systems. Hindutva, also termed Hinduness, is an essence of qualities of Hindu dharma that are perennial and common to all the religions born out of its Vedic knowledge. Many of the distinct characteristics of Hindu society are purely cultural habits ingrained in its members for aeons and common across the geography of Bharat. This realisation is quite a surprise for the readers.

Ratan Sharda explains that Sarsanghchalak is not the executive head, but he is the guide and philosopher of the organisation. He is also the face of the organisation. His word carries weight within and outside the organisation

The writer dedicates chapters to explain the evolution of RSS from an organisation to a movement very succinctly. The reader is able to grasp the reason behind the sustained growth of the organisation and stages through which it has passed to reach a stage where it has become the organisation of the society and not within the society as envisaged by its founder, who began this work without any resources with about a dozen teenagers, playing kabaddi in the ground in Nagpur. He explains the different inflexion points in this long journey and how RSS leadership was able to adjust sails to the changing winds, sometimes stormy. The ability of the leadership to judge issues with the vision of a strong nation, its ability to reach out and co-opt every section of the society across the nation that shows its vitality is highlighted in the book. One can understand the meaning of Dr Hedgewar's prophetic words that RSS will not do anything, swayamsevak will do everything, as one reads about the rise of different organisations inspired by RSS, including those by swayamsevaks who went overseas.

An outstanding enunciation of RSS world view in the book is presented in the chapter, 'Expanding Hindutva' scope. This chapter may be considered the highlight of the book. Here, the writer explains the origin of the term 'Hindutva' and its interpretation by different thinkers and leaders. The writer moves to take the reader through the finer points in this historical progression of the term and the movement. He explains how and where Savarkar and RSS are on the same page and where they are not. He digs out Vishwa Hindu Parishad's foundational shloka from archives that show the expansive world view that included Hindus overseas and future Hindus. He shows that while Hindutva retains its essential meaning, it also expands to include and assimilate more and more communities and people within its folds, directly or indirectly, securing their distinct identities. To his credit, the author grasped the possibility of further expansion of the idea of Hindutva based on some pronouncements by current RSS chief Dr Mohan Bhagwat's about the position of minority communities in India a few months back. He is frank enough to admit that there may be opposition to what Dr Bhagwat has said and reasons that Dr Hedgewar, too, had faced similar opposition when he propounded the idea of Hindu Rashtra when he founded RSS.

This book shows the writer's deep understanding of the RSS and its organisational and intellectual evolution. His simplicity and easy to understand flow of ideas make this book a compulsive read for the people who really wish to understand the organisation well.

Comments