Dr Hedgewar would as heartily go along with a patriotic Muslim as he would do with a patriotic Hindu. He made no distinction merely because of one’s religious beliefs

The mission of Hindu consolidation that revered Dr Hedgewar had conceived of in the form of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh was based on sure and solid historical grounds: This nation of ours was not born yesterday. No one knows its origin. When the world opened its eyes, our nation was already at the zenith of greatness and glory. In fact, many parts of the world opened their eyes because of our great forbears who had reached there carrying the light of human culture and civilisation.

History also tells us that the people who built and nurtured this great nation of ours have been since long known as Hindus all over the world. And this, long-long before Islam or Christianity appeared on the world-stage. It is natural, the fate of this nation has been, since then, inextricably bound with that of the Hindus. So long as the Hindus remained organised and intensely conscious of their great national ideals, the nation rapidly progressed and rose to heights of prosperity and power. But, in course of time, when disunity crept in and they became splintered and oblivious of their unique national identity, the nation gradually slipped into slavery and all-round degeneration. In short, with the rise of Hindus, the nation also rose and with their downfall the nation also fell.

History also tells us that the people who built and nurtured this great nation of ours have been since long known as Hindus all over the world. And this, long-long before Islam or Christianity appeared on the world-stage. It is natural, the fate of this nation has been, since then, inextricably bound with that of the Hindus. So long as the Hindus remained organised and intensely conscious of their great national ideals, the nation rapidly progressed and rose to heights of prosperity and power. But, in course of time, when disunity crept in and they became splintered and oblivious of their unique national identity, the nation gradually slipped into slavery and all-round degeneration. In short, with the rise of Hindus, the nation also rose and with their downfall the nation also fell.

National Emancipation

Dr Hedgewar, therefore, concluded that the secret of national emancipation lay in rejuvenating and reorganising the Hindu people as a self-assured, well-knit, and powerful social entity. There was no place in this line of thinking for finding fault with others and holding them responsible for our downfall. It was entirely a positive approach of self-correction and self-renewal.

At the same time, Dr Hedgewar had not shut his eyes to hard realities of contemporary developments. He was as much fully alive to the present as to the past. Nor was he an armchair theoretician trying to arrive at airy solutions. He was, from his boyhood, totally and actively identified with various movements for national liberation. The fund of practical experience and the keen insight he had acquired thereby had given him an assessment of the contemporary developments.

With the advent of Muslims as aggressors on our land, a new challenge had developed on our national scene. Their past history and their contemporary trends both pointed to the same conclusion that they were hell-bent on destroying the very fabric and soul of our national entity. They appeared dead opposed to every single aspect of the national life here—its life-values, points of honour, its heroes, and even the unity and sanctity of motherland. All the goodwill and generosity showered upon them had only proved counter-productive; it had only further whetted their aggressive nature. All that the country got by way of reward was countrywide gruesome riots climaxing in the terrible Moplah holocaust.

In the then prevalent situation, Doctorji’s uncompromising nationalist stand vis-à-vis Muslims, however, did not allow his mental clarity to be clouded by anti-somebody complexes. He would not keep off from or much less hate the Muslims just because they were Muslims. And, throughout his life, he maintained this noble attitude even under most trying situations. He could be one with patriotic Muslims without the least trace of mental reservations. The one and only consideration that weighed with him was unalloyed love for our country and our culture. And wherever he noticed it, he would feel oneself with it. He would as heartily go along with a patriotic Muslim as he would do with a patriotic Hindu. He made no distinction merely because of one’s religious beliefs.

Swadeshi Bhakt

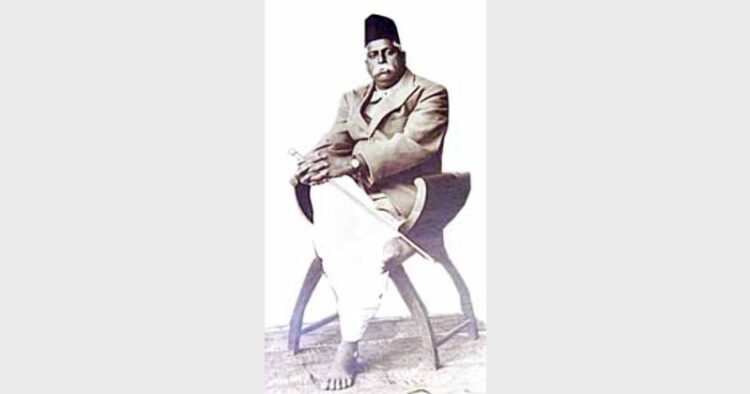

Doctorji’s deep love for Maulvi Liaquat Hussain, while he was in Calcutta, makes a revealing instance in point. Doctorji was then in his early twenties whereas the Maulvi was on the other side of sixty. Maulvi Saheb was a devout follower of Lokamanya Tilak and a swadeshi bhakt. He ran a Swadeshi provision store also to popularise Swadeshi. Though poor by himself, he was always busy collecting funds for the needy. Helping poor students for their education was his special love. His patriotic ventures would often land him in prison. No wonder, the young Doctor Hedgewar felt fascinated by him. He, with his friends, would join the prabhat pheris and the public meetings that Maulvi Saheb would organise. Once, when he fell ill, Doctorji stayed with him to serve him day and night.

For all his patriotism—Maulvi Saheb was also a bit eccentric. Once, the King and Queen of England were to visit Calcutta. A big public reception with guard of honour, demonstrations and all that was arranged. The Maulvi Saheb also got a fit of loyalty and marched with all imposing gaiety and dignity through the police cordon to give hand-shake to the royal couple! Doctorji and his young friends too joined the party. They felt it was a nice chance to see the military formations from close quarters. This strange Maulvi-led procession pressed forward chanting Rajar Jai Raneer Jai (Victory to the King and the Queen) but after a distance, a British officer stopped them and unceremoniously turned them back. The Maulvi Saheb with his devoted chelas marched back with equal gusto but with a changed tune! The song Jago jago re Bharat santan (Wake up sons and daughters of India) and other revolutionary couplets—now formed their new refrain!

Though Doctorji was sore at having missed a fine opportunity of observing the military movements, his love for him never waned even a whit. One wonders how Doctorji—such an incisive judge of men and matters—came to be so much attached to that Maulvi Saheb. The reason was clear. Doctorji was one who cared little for external oddities. In Maulvi Saheb he had recognised the heart, simple and pure, as that of a child and at the same time having flaming love for the country and that was enough for Doctorji.

Sincere and Direct Appeal

Samiullah Khan of Nagpur was a known figure in the freedom movement of those days. As such, Doctorji knew him intimately. When Doctorji was convicted to undergo one year’s rigorous imprisonment (RI) in 1921 for his fiery speeches during the non-cooperation movement, Samiullah Khan was among the prominent Congress leaders who had come to garland and give him a warm send-off before his going the jail. When Khansaheb was elected Municipal President of Nagpur, Doctorji offered him his heartfelt compliments.

He told Khansaheb in own charming style: “Khansaheb, now that you have become our Municipal Chairman, I feel as if one of my own household members is adorning that august office.” Later on, once when Doctorji had gone to his office for some work, he told Doctorji. “Doctorsaheb, why should you have taken all the trouble of coming here? You could have just sent a message and it would have been my pleasure to come to you and seen that the work is done.”

There was nothing artificial or tactical in all this. Doctorji’s sincerity was transparent and his appeal direct. As such many times it happened that even those “who came to scoff, remained to pray.” At Murtzapur, a public speech during Ganeshotsav by Doctorji was just over. Just then, from a corner of the meeting a Muslim began pushing forward to reach Doctorji. But, others stopped him. They were apprehensive about his intentions because those were the days of acute communal tension. And Doctorji had received quite a few threatening letters. But the Muslim persisted in meeting Doctorji. When Doctorji sensed what was going on, he instructed others to let him come near. The Muslim came and offered Doctorji a garland and said: “Well, Doctorsaheb, I had so many times heard from my Muslim friends that you are an arch Muslim-hater. So, I purposely came today from my place to listen to you expecting that you would pour out your venom against the Muslims. But to my surprise, I found not a single word that would offend my religious susceptibilities. Every sentence of your speech bespoke only of intense patriotic fervour, with no place for any rancour or ill will for any one.”

In 1932, the Government of Central Provinces issued orders prohibiting Government servants from attending Sangh Shakhas and later on extended the order to cover the Municipal and District and Local Board employees. A hot debate ensued in the Legislative Council. Among the independent members who took the Government to task was S.M. Rahaman from Berar. He squarely nailed the lie indulged in by the Home Member that Sangh was communal, fascist, political and what not and pointed out that no Muslim organisation had raised any objection to the Sangh during its entire seven years of existence.

Old Arab Sepoy

The spontaneous remark of an old Arab sepoy on seeing the Vijaya Dashmi route march of Sangh at Nagpur is extremely significant. The sepoy was very old—probably in his late nineties and had been once employed in Bhonsle Raja’s service. It was said that he had taken part in the final battle of the Bhonsles with the English and was a painful witness to the burning down of the royal palace, which went on smouldering for full six months. When the disciplined march of the youthful swayamsevaks passed before the palace and the old sepoy witnessed it, his eyes welled up with tears. He just remarked: “Who says that the Sangh is anti-Musalman? Just replace the sticks in their hands with rifles and the job will be over!”

It is obvious this attitude of Muslims towards Sangh was a natural reciprocation of Doctorji’s attitude towards them. And Doctorji’s attitude itself was not based on any fleeting political considerations. He knew that a policy of political bargaining to win over Muslims would do no good. That would not change their mental outlook. And without change of mental attitudes no permanent unity would be possible. Enduring national union of hearts, Doctorji felt, could be achieved only by rousing certain convictions—basic to the national life.

Muslims here, after all, belonged to the same parental stock as the Hindus. Maybe their mental complexes had, due to some historical reasons, undergone some changes, but their ‘blood’ had remained very much the same as that of Hindus. And Doctorji also knew that none among them could shut their eyes to the historical reality that some decades or centuries ago they were Hindus. And he was also confident that with a congenial change in their attitude, they would certainly love to cherish once again their old racial memories and join in all national endeavours. Doctorji was convinced that there could be no other alternative, except taking up this intensely national and at the same time entirely rational attitude.

Yadava Rao Joshi (Reproduced from Organiser’s Deepavali Special issue dated November 6, 1988. The writer was then Sah Sarkaryavah of RSS)

Comments