Supreme Court ruling on Novartis’ Plea to prove

This case of Swiss MNC, Novartis, challenging Indian patent law in Supreme Court, has invoked worldwide protests against it.

Dr Bhagwati Prakash Sharma

If the Swiss MNC Novartis wins the patent case scheduled for hearing in the Supreme Court of India on July 10, 2012 it would:

* Spell a death knell for blood cancer patients in India and abroad

* Pave the way for evergreening of patents and for grant of frivolous patents there by leading to manifold increase in prices of hundreds of life saving drugs

* Endanger the pharmaceuticals industry in India as well as education and research in pharmacy, ultimately making India foreign dependent in health care and pharma sector.

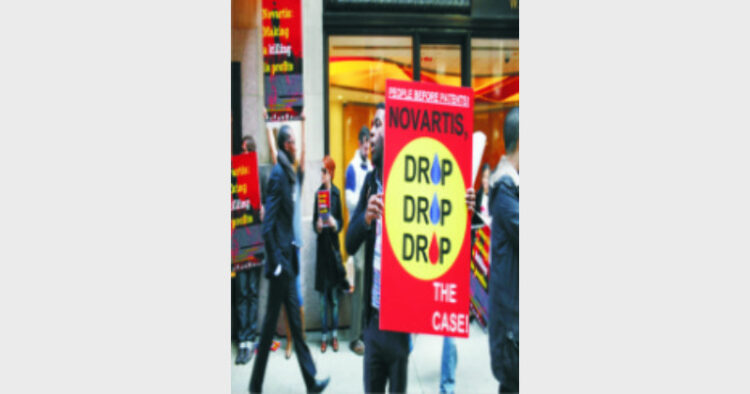

Protest growing world over against Novartis

The ultimate ruling of the Supreme Court (SC) on plea of the Swiss pharma company, Novartis, challenging the validity of Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act and scheduled for hearing on July 10, 2012, would be crucial to stop evergreening of patents in India, which otherwise, is likely to seriously jeopardise availability of life saving drugs at affordable prices. Acceptance of the plea of Novartis would also endanger the Indian pharmaceutical sector, comprising 20,000 plus pharma companies, besides, undermining the R&D and education in the field of Pharmacy in India. The Supreme Court has to decide, whether the government had the right to deny a patent to Novartis for its anti-blood cancer medicine, Glivec, which it is selling at the rate of Rs 1000 per capsule in India vis a vis the generic versions being made available by Indian generic manufacturers at a price as low as Rs 90. If the Novartis plea is accepted, all generic manufacturers offering this drug between Rs 90 to 130 per capsule in India shall be stopped from manufacturing this drug and eventually, it (Novartis) may start charging Rs 1400 per capsule as is being done by it elsewhere. This would deny access to this life saving medicine to almost 90 per cent of the 40,000 plus blood cancer patients in India and more than 2 lakh patients worldwide. Recently, it has also been found very effective against gastrointestinal cancer. So, it is the potential ray of hope for around a million cancer patients. Poor patients in more than 60 countries are also dependent on the imported generic versions of Indian origin, as it is not available for less than Rs 1400 per 100 mg tablet, which they cannot afford, and shall have to wait for a painful death. Even, for almost 1,70,000 patients spread into 16 countries this cheaper generic version of Glivec, available at less than Rs 90 per tablet is also not affordable. Therefore, they are dependent upon a French NGO ‘Medicines Sans Frontiers’ (MSF), which imports it from India and distributes free of cost. A much bigger number of patients are being treated worldwide by Cancer Patients Aid Association (CPAA). But, It would be out of reach for such philanthropic associations too to keep this vast number of cancer patients alive by distributing free medicines, if the Novartis wins and generic manufacturers are stopped from producing and selling it at affordable prices. Even in India alone, where the generic version is available, almost 18,000 people die a very painful death every year, as the treatment cost per day comes to Rs 360 a day, with 4 pills a day which they cannot afford (while, the Navartis charges Rs 1420 per tablet so treatment cost would be Rs 5680 per day and Rs 1,70,400 per month). The question, therefore, arises is that if the Novartis wins, then how many of the 24,000 patients contacting blood cancer every year will be able to continue their treatment at Rs 1420 per tablet and moreover when the treatment cost would shoot to Rs 5680 per day. Moreover, the Novartis might then charge much higher price up to 7-10 thousand also if it acquires monopoly.

A Novartis victory in this case would equip all the multinational pharma patent holder companies with the right of perpetual evergreening of their patents. They would then keep on extending their patents by introducing minor changes in their drugs and shall permanently inhibit introduction of cheaper generic molecules at affordable costs. This would also deprive many of the generic manufacturers who have introduced medicines at less than 1 to 3 per cent of the original price being charged by the patent holder for that medicine.

India is the only country producing and selling costly life saving medicines at just 1-3 per cent of the prices being charged by the monopoly patent holders worldwide, and therefore, NGOs like MSF (which treats 40 per cent of AIDS patients worldwide free) buys 80 of their generic AIDS drugs from India. Novartis victory would cause a lethal blow to health care worldwide, besides, jeopardising the future of generics industry in India, which is making available, all medicines at just 1 to 3 per cent of their international prices in India and in many countries abroad. Almost, more than 90 per cent of all medicines are 10 to 60 times costlier in all the other 200 countries except India.

The amendments in Indian Patents Act in 1999 and 2005 have already deprived Indian generic drug manufacturers from their right to manufacture any drug molecule invented after January 1, 1995 by evolving their own processes. Therefore, all newer molecules would continue to be unaffordable for common masses for years to come. Since, 97 per cent of the drugs being prescribed in India by the doctors are older molecules, invented before January 1, 1995 so, they are better affordable. But, gradually, when the older molecules would lose their efficacy or be banned or better newer molecules emerge, these newer molecules would be out of reach of masses jeopardising public health.

This single case of astronomical difference in the price of Glivec (Rs 90 v/s Rs 1000 per capsule), out of hundreds of such examples reflecting the dangers of ‘Product Patents Regime’ is enough to arouse the public opinion against this new ‘Product Patents Regime. This case of Novatise began, when the Indian Patent office granted exclusive marketing rights (EMR) to Novartis for its anti-cancer drug Imantinib in pursuance of an amendment in the Indian Patents Act in 1999 to comply with the agreement on Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the WTO, with effect from January 1, 1995. Novartis was having an international patent for this molecule since 1993. So, it was neither eligible for an EMR nor for a product patent for this product. But it (Novartis) began enforcing the EMR for Glivec (Imantinib) by asking Madras High Court to restrain generic manufacturers, like Cipla, Ranbaxy, Sun and Hetero, from manufacturing, selling, distributing and exporting this anticancer drug Imantinib (branded as Glivec). The Court, unfortunately granted an injunction in January 2004, which was later made absolute by a single judge of the High Court.

To comply with this Court order, the generic manufacturers had to stop producing and selling Imantinib and the price of it jumped from Rs 90 per 100 mg capsule to Rs 1000 per capsule in India. It is being alleged that thousands of patients suffering from chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), a life threatening form of blood cancer, had to succumb to death from this disease, who could not continue the treatment after this jump-over in price due to Novartis monopoly.

Since, EMR was a transient arrangement, that too under a mailbox facility defying any scrutiny till December 31, 2004, so, in 2005 India amended its patent law to comply with agreement on TRIPS (of the WTO) to provide for product patent. However, on the apt counsel of the late BK Kaeyla and pressure campaigning of the organisations like Swadeshi Jagran Manch, the Parliament had simultaneously introduced a significant provision to prevent evergreening of patents and also to prevent frivolous patents – ie the Section 3 (d), which disallows patents on incremental research without any meaningful improvement in the original product covered by an earlier patent.

So, after the transient arrangement for EMR was over and the application of Novartis for grant of patent on Imantinib (Glevic) was pending in the patent office, the CPAA and four generic manufactures which were earlier selling this medicine at better affordable price, filed a pre-grant opposition to oppose the grant of patent for Imantinib to Novartis on the plea that Novartis has a patent on this molecule since 1993, so, this molecule is older than 1995 and the newer version for which it had filed an application in 1997 into the Indian Patent Office has no marked difference. So, in January the Patent Controller in Chennei, in a landmark decision, refused to grant Novartis a patent on Imantinib (branded as Glivec) agreeing with the contention that the product under consideration for grant of patent lacked novelty over its earlier patent of 1993, was obvious and not patentable under Section 3(d). Novartis, thereafter, had lost its case before the Intellectual Property Appealtate Board (IPAB) as well, when it appealed against the rejection of its patent application.

With the rejection of patent application by the Indian patent office, generic companies got free to produce and sell the generic version of the Imantinib molecule in India and abroad. So, they resumed supplies at just 1/11th of the Novartis’ price in India, and at 1/20th of its price abroad. Now the case is pending in the Supreme Court, wherein the Novartis has requested to scrap Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act, as its patent application was rejected under this Sections which disallows patents on incremental research without any marked improvement in original product.

Worldover, more than 2 lakh blood cancer patients are surviving, painlessly, by consuming this medicine being made available at affordable price by the Indian generic companies, solely by virtue of Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act. In India alone, 24,000 people are afflicted by CML (blood cancer) every year and 18,000 succumb to the disease, mainly because they cannot afford to buy even these cheaper generic brands.

Therefore, the awakened sections of society have already begun to fortify world over against the Novartis case in India. Recently, during the run up to the annual general meeting of the shareholders of Novartis company in Basel (Switzerland) on February 23, 2012, protests were held in various cities of US and Europe demanding Novartis to drop its case in Indian Supreme Court. Demonstrations were organised in Cambridge, Massachuselts, Basel and so on in front of Novartis office world over. More than 50,000 signatures have been collected on an internet petition as part of a social media campaign.

But, unfortunately these protests organised worldwide have gone unnoticed in India and protests against Novartis in India are lack luster. While, scrapping of Section 3 (d) of the Indian Patents Act would not only eliminate affordable generic versions of this anti-cancer drug Glivec alone, but, would lead to evergreening of hundreds of patents of other life saving drugs, now and in the years to come. Not more than 10 per cent of the total 24,000 pharma firms of India would survive beyond 2020 if the Section 3(d) is scrapped. Consequently, people in India would find it hard to have access to better and effective drugs, invented not only after 1995 but even before 1995. Majority of the medical practitioners too would be deprived of practice on and prescribe newer molecules, which would be beyond the reach of common man. Majority of Indian middle class shall have to siphon out 10-15 per cent of their monthly income on health insurance to get access to the newer molecules, as many MNC pharma lobbies would not hesitate to sponsor fake researches to generate evidence against the patent older molecules for a ban against them.

Therefore, activists and organisations should launch a powerful mass movement against Novartis to compell it to withdraw the case. Organisations of patriotic and humane medical practitioners, should also put pressure by the threat of total boycott of Novartis products if it insists on scrapping of the Section 3 (d) of the Indian Patents Act. Medical practitioners’ associations should also appear as intervener in the SC to counter the controversial claim of Novartis that there is any marked novelty in the beta crystalline form of Imantinib mesylate, for which it has applied for a patent in 1997, over the Imantinib mesylate of the free base, Imantinib patented in 1993. The Novartis’ claim for a fresh patent is liable to be rejected if the medicos can prove that beta crystalline form of Imantinib mesylate is not a novelty worth grant of a patent over its earlier patent of 1993.

Comments