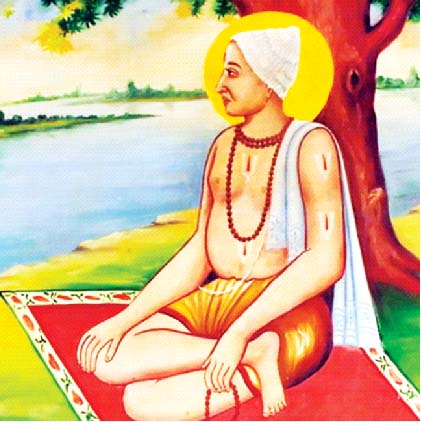

The epic story of Bhagwan Ram, composed in Hindi more than four centuries ago, by a towering intellectual Goswami Tulsidasji, the Ramcharitmanas remains a most meditated, constantly searched, yet less researched text of our time.

At the beginning of the 20th Century, during the intense days of the freedom movement in India, the Indians took refuge in the Awadhi-Braj text, singing and drawing inspiration from its deep verses, known as chaupais, dohas, sorthas and chandas. The twentieth Century commentators of the West, especially from Britain, would describe the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas as “the best and most trustworthy guide to the popular living faith of the people” (JM Macfie, 1930), and Mahatama Gandhi, the greatest practitioner of the faith in Ram of the time, described the Ramcharitmanas as the “ greatest book” in the world.

So, when non-Sanskrit literature, written for the benefit of the masses of India acquires the status of a ‘Great Tradition’ in a different time in history, it signals an extension and proliferation of that tradition and not the end of a great tradition. In the great Indian epic, the Ramayana, composed about four thousand years ago in Sanskrit, the lure of this royal story hardly requires an introduction. The story of Prince Ram, the protagonist of the epic, replicated in hundreds of languages of India and beyond over the last three millennia, has turned this story into the proverbial narrative of the houses of millions of Indians. The majesty of the story of Ram itself makes the Ramcharitmanas so enchanting. The power of Tulsidas’s Ramayana works at three levels: the nature of language, the memory or the structure of the story and the felicity of the medium. And the most important connecting thread at these levels is the storytelling tradition. When I was small, I was drawn in my village to the rhythmic chanting of a text which I knew then as the Ramayana; the sound of cymbals, drums (or dholak, as it is called in most parts of North India), also harmonium, which often accompanied the orchestral chanting, beckoned many of us village folks. This was one singing to which nobody in the community objected as a moral digression; it was considered not merely a religious prayer but a sound that would purify the space of the village as far as it reached. Organising the chanting (or patha) of the Ramcharitmamas was considered a good deed (punya); it would be an act of ‘thanks giving’ on various auspicious occasions: the birth of a child, tonsure ceremony of a child, acquiring good marks in an important exam, landing a good job, wedding ceremony, a rich harvest, a victory in a lawsuit and so on.

Respect in Hindi Heartland

It is not that the people in the village knew no other Hindu rituals or did not bother to perform them; from their point of view, all prescribed rituals for the respective occasions were given their due importance; but the recitation of the Ramcharitmanas was very special indeed. Also, perhaps, the recitation or chanting of Tulsidas’s Ramayan requires no elaborate rituals, no priest, no paraphernalia. The host, at the most, may enlist a group of chanters, if he or she doesn’t wish to do it solo. This Ramayana, in Awadhi, the language of my village, is treated with great reverence and awe; it is considered holy, and it is singable. I would learn later, too, as a grown up, that its magic was almost universal in what is known as the ‘Hindi Heartland’ of India. The book is almost like a living encyclopaedia, providing solutions to many predicaments of life. The recitation of the Ramcharitmamas by a school-going kid without a fault or fluff would be an index of a good, prospering mind; chanting it melodiously was a bonus; committing to one’s memory, even a few verses of it, a gift.

It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that every great poet of India, over the past three thousand years in the many languages, has been inspired by the two Sanskrit epics. But Tulsidas’s Ramayana acquires a special place

Why? The answer to this question could be neither singular nor easy. As far as I can understand, Tulsidas’s Ramayan represents what was called, in the early part of the twentieth century, the “cultural consciousness” of India. Some have even called it the “national consciousness” of the people of India. Let me approach to answer the above question in two folds: one, an assertion of an identity of a civilisation through its cultural heritage, and two, a cultural attempt to bring about the so-called lost order in a society.

Awadhi Ramayana Inspired Epics

Like any learned person of his time, Tulsidas was alive to the cultural heritage of his country and could, therefore, assess the power of the psychedelically mesmerising, idealistically desirable world represented by the legendary Sanskrit epic, the Ramayan, the stories of which have always been the source of inspiring proverbs of common Indian discourse. It acted as a fountain of inspiration for hundreds of epics and poems in the many languages of India; Tulsidas’s Awadhi Ramayan is only one, but unarguably the most celebrated epic of them all. The great Hindi poets – Sumitranandan Pant, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, Suryakanta Tripathi Nirala, Mathili Sharan Gupta, Harivansh Rai Bachchan – to name a few great Hindi doyens of 20th Century India, were inspired by Tulsidas’s Ramayana and, of course, by its original source, the great Sanskrit epic. They composed their respective works on the various episodes of the Ramayan, as also on the other Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata. The two epics have shaped India’s cultural, intellectual, literary and social life. It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that every great poet of India, over the past three thousand years in the many languages of India has been inspired by the two Sanskrit epics. But Tulsidas’s Ramayan acquires a special place; it is faithful to the original story of Bhagwan Ram and is different from every other version of the Ramayana.

The American Indianist, Philip Lutgendorf, has extensively studied the Ramcharitmanas and its influence over India’s large population over the centuries. His book, The Life of a Text: Performing the Rāmcaritmānas of Tulsidas (1994), is richly endowed with various aspects of the role Tulsi’s Ramayan has played, how it has been used, appropriated, also rejected by various groups in India for various reasons and agendas. The recent controversy – ironically, though, similar controversies surrounding Tulsidas’s Ramayan have been heard before and many times – that Tulsidas was not sensitive to the structure of Indian society seems to be born out of sheer ignorance of the people, who fail to understand the nature of epic and history of a society, especially of India.

Tulsidas was concerned about the Hindu society which at his time was getting disintegrated into various camps, groups and sects. He was also conscious of the administrative rule prevailing during his time. He may not have been sure about the intellectual risk he took by composing the Ramayan in the language of the villagers (gramya), but he was supremely confident about the content of his cause; admittedly, he was also certain about the power of the story of Ram: “My pool of good deed (bhaga) may be tiny but I have a lofty ambition; I am certain of one thing, though: when good people will hear the story of Ram, they’ll enjoy it; only the wicked will make fun of it. I am aware, too, that my language is raw and lacks all poetic tropes, but it celebrates singular, world-famous merit, realising that alone the intelligent and the pure-minded people will pay heed to it.” (1.8) He further justifies: “Just like people drink the milk of a black cow (syāmasurabhi), because it is pure and rich in proteins; similarly, the wise will surely like to hear and narrate the story of Rāma, even though it may be written in the language of the peasants.” (1.10b)

Tulsidas was concerned about the Hindu society, which at his time was getting disintegrated into various camps, groups and sects. He was also conscious of the administrative rule prevailing during his time

Tulsidas has succeeded in his mission of bringing about unity among the Hindus of various sects, most importantly, the two major factions of Shaivism and Vaishnavism, because his Ramcharitmanas is the first medieval devotional work, which attempted the unity, the synthesis, between the two warring factions of the Hindus. For his devotional moorings, Tulsidas was inspired by the Bhagavata tradition, which is evident not only from his Ramayan but also from his other two famous treatises, the Kavitavali and the Vinayapatrika. When he was questioned on his singular love for Tulsidas’s Ramayan, despite the many so-called controversial statements there, Mahatma Gandhi (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume XXIX, 1925) had cautioned the readers and chanters of Tulsidas that in determining the meaning of a text like the Ramcharitmanas, “one should not stick to its letter, but try to understand its spirit, its meaning in the total context.” Whether such a justification, or justification through ‘a common belief’, is good enough is difficult to say. Still, the story of Ram and the legends related to it continue to inspire and thrill many today.

( Centre for Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences, JNU )

Comments