The foundation of Indian Forest Policy was laid down during the early 19th Century in Britain where the Industrial Revolution was taking its pace. Due to the Industrial Revolution, the price of timber in England was increasing. As a result, domestic quantities became scarce and more difficult to obtain. Many industries thus were forced to change to substitutes. In the end, England exhausted its supply of suitable domestic hardwood timber and became dependent on other nation’s natural resources, trees and wood.

Thus, Britain started to import timber from the Baltic regions but it had two notable drawbacks. The first was one of economics; the British had a large trade deficit with the entire Baltic region. Great Britain required a large number of essential resources from the Baltic, but did not have enough goods to export to the Baltic to make up for these purchases. This imbalance caused great displeasure among the mercantilists and economists thus forcing Britain to look to other nations especially their colonised nations to loot their natural resources to balance their trade deficit and increase their prosperity. Second, by the early 19th Century, oak forests in England were disappearing, British desperately needed timber supply for their Royal Navy because manufacturing of naval ship required large numbers of timbers which was unavailable in the local market. Therefore, they sent search parties to explore forest resources of India in 1820. Within a decade vast quantities of timber were being exported from India, not only for their Royal Navy purpose but also for the movement of imperial troops. Further they started to explore the valuable minerals and natural resources of India through the expansion of their rail network for colonial trade. To run locomotives, they needed wood and also for railway tracks they needed timber supply. To meet this demand, extensive wood cutting started and under the British colonial rule the process of deforestation for economic development in India became systematic and extensive. In fact, strategically, large areas of natural forests were cleared to make way for tea, coffee and rubber plantations to meet Europe’s growing need for these commodities.

Unsung Heroes

Uda Devi

Uda Devi was born in a small village in Awadh, Uttar Pradesh. Seeing the rising anger of the Indian people against the British administration, she reached out to Begum Hazrat Mahal to enlist for war. In order to prepare for the battle that was headed their way, the Begum helped her form a women’s battalion under her command.

Uda Devi and her Dalit sisters were the warriors or Veeranginis of the 1857 Indian War of Independence against the British East India Company. Today Uda Devi is an inspiration to women from non-dominant castes. Each year, on November 16, members of the Pasi caste gather at the sight of her final plunge and celebrate her as an anti-imperialist rebel who defied convention and struck a blow for the embryonic cause of Indian Independence.

]Colonialists Clear Forest

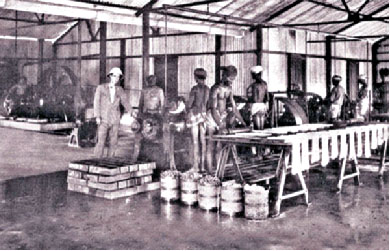

To maintain the adequate supply, the Colonial Government took over the forests and gave vast areas to European planters at cheap rates resulting in the expansion of cultivation in the colonial period. The British directly encouraged the production of commercial crops like jute, sugar wheat and cotton. These crops were essential products for the consumption of urban population and also for the raw materials needed in industrial production. The colonial power thought that revenue generated from agricultural activities were significant compared to the forest, so they tried to expand agriculture by clearing forests which would enhance the revenue of the state. Between 1880 and 1920, cultivated area in India rose by 6.7 million hectares. Since, the British Government wanted to take full control of India’s natural resources and for that purpose, in 1856, Dr Brandis was appointed as Superintendent of Forest in Pegu (Mayanmar). Later, he joined the Indian Government as the first Inspector General of Forests and shaped the destiny of Indian woodlands. But interestingly, around 1850 Britain had no forestry service and there was no formal training of foresters. Forestry was still practised in the context of estates mainly owned by aristocracy and managed by foresters who had learned traditional management techniques under an apprentice system from their predecessors. In fact, the British Government and many landowners did not feel the necessity to increase timber production and introduce modern formalised forestry practices from the continent because the British had direct access to the large timber reserves of their Empire, of Scandinavia and the Baltic states. Importing timber from overseas was much cheaper than to produce it back home in Britain. So, it clearly indicates that the main purpose of the colonial ruler was to systematically loot the forest reserve of India rather than conservation.

Unsung Heroes

Thalakkal Chandu

Thalakkal Chandu was a popular name in the field of archery in India. Chandu was an archer and the commander-in-chief of the Kurichya soldiers of Pazhassi Raja who fought the forces of British Empire in the Wayanad Jungles in the early times of the 19th century. Chandu started his career under the patronage of Edachena Kunkan, who latter promoted him to one of Raja generals. Pazhassi Raja as well as his generals and troops saw Chandu as their capable war leader. For five years, Pazhassi Raja survived and continued his battle against the East India Company with the help of the Kurichiyas and Kurumas. The rebellion on October 11, 1802 by a group of tribal soldiers led by Thalakkal Chandu and Edachena Kunkan, resulted in the capturethe British fort at Panamaram. The British forces launched a retaliatory attack and trapped Thalakkal Chandu on November 15, 1805. He was executed under a Koly tree.

Dietrich Brandis set up the Indian Forest Service (IFS) in 1864 and helped formulate the Indian Forest Act of 1865. The Indian Forest Act of 1865 extended British colonialism in India and claimed over forests in India. The 1865 act was a precursor to the Forest Act of 1878, which truncated the centuries-old traditional use by communities of their forests and secured the colonial governments control over the forestry. The section 3 of 1865 Act says that, “The State Government may constitute any forest-land or waste-land which is the property of Government, or over which the Government has proprietary rights, or to the whole or any part of the forest-produce of which the Government is entitled, a reserved forest in the manner hereinafter provided at a bigger scale”. This section 3 clearly indicates that colonial ruler could declare any land a forest land/reserve to meet their own need and because there was no definition of ”forest” in the 1865 act they could restrict the traditional practices of locals inhabitants of that area using the forest policy acts.

Importing timber from overseas was much cheaper than to produce it back home in Britain. So, it clearly indicates that the main purpose of the colonial ruler was to systematically loot the forest reserve of India rather than conservation

Further Section 2 of 1865 Act says that, forest produce that is part of natural resources are, “ timber, charcoal, caoutchouc, catechu, wood-oil, resin, natural varnish, bark, lac, mahua flowers, mahua seeds, myrabolans, trees and leaves, flowers and fruits, including grass, creepers, reeds and moss wild animals and skins, tusks, horns, bones, silk, cocoons, honey and wax, peat, surface soil, rock and minerals (including lime-stone, laterite, mineral oils, and all products of mines or quarries)”. These kinds of act instantly exercised powers for monopolising the extortion from these Treasured Areas; thereby initiated a rule and later enacted as a legal binding, which conclusively protected them, providing them exclusivity in the field of such extortion, securing them in extraction of forest products of every nature, from its length and breadth. As a result, the tribal communities of India that have always been very conservative in nature and wanted to retain features of their society and natural ecosystem started to raise their voice. Interference in their way of living by colonial rulers agitates diverse tribal communities from various regions of India that led to a revolt against the exploitative and discriminatory practices of the British Indian Government during the time of British rule. For instance, Bhil Uprising (1818-1831); Bhils belonged to the Khandesh region of Maharashtra. In 1818, the British made their way into the area and began encroaching on the Bhil territories. The native Bhil Tribe was in no way prepared to accept any British changes made on their land. As a result they revolted against the foreigners on the land. The reason for the uprising was the brutal treatment of the Bhils at the hands of the East India Company who denied them their traditional forest rights and exploited them. The British responded by sending a force to suppress the rebellion.

Unsung Heroes

Trilochan Pokhrel

Trilochan Pokhrel was born to Bhadralal and Januka Pokhrel and brought up at Tareythang Busty in the Pakyong subdivision of East Sikkim in the last decade of 19th Century. During his youth, he was greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi which were based on the fundamental principles of truth and non-violence. He stayed with Gandhiji at the Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat and the Sarvodaya Ashram in Bihar. During his stay there, Pokhrel is known to have spent his time spinning the Charkha and rendering his services for the ashrams and assisting Gandhi in his daily affairs. Akin to Gandhiji, he too wore a piece of cotton dhoti and a pair of Khadau or wooden slippers . It is said that he used to greet elders in the village with ‘Bande Mataram’. This prompted some people in his village to refer to him as ‘Bande Pokhrel’. He used to convey the message of Vande Mataram and inculcate the spirit of Swadeshi Movement.

Khond Uprising (1837-56); the Khonds inhabited the mountainous regions that ran from Bengal to Tamil Nadu as well as the central provinces. Due to the impassable hilly terrain, they were entirely independent before the British arrived. Between 1837 to 1856, they rose against the British for their exploitation of forest practices, led by Chakra Bisoi, who adopted the name “Young Raja.” Koya Uprising (1879- 1880). Assisted by Khonda Sara commanders, the Koyas of the eastern Godavari track (now Andhra) revolted in 1803, 1840, 1845, 1858, 1861, and 1862. They rose once again under Tomma Sora in 1879–1880. They complained about being persecuted by the police and moneylenders, new limitations and the denial of their historical rights to forest areas. The prime cause of revolt by these tribes were mainly due to the restricting the practice of settled agriculture: The tribals’ mainstay were shifting agriculture, hunting, fishing and the use of forest produce. With the influx of non-tribals into the traditional regions of the tribals, the practice of settled agriculture was introduced. This led to a loss of land for the tribal population. The tribals were reduced to being landless agricultural labourers. There were restrictions imposed on the use of forest produce, on shifting agriculture and on hunting practices. This led to the loss of livelihood for the tribals.

Unsung Heroes

Veer Narayan Singh

Veer Narayan Singh was a landlord from Sonakhan, Chhattisgarh. He spearheaded the 1857 War of Indian independence in Chhattisgarh. He is also known and considered as the 1st Chhattisgarhi freedom fighter. In 1856 when Chhattisgarh was in the grip of severe famine, Narayan Simgh, performing the duties of a ‘Kshetra Pramukh‘, arranged to take out grain from the warehouse and distributed it amongst the people. But on the complaint of a merchant, the British Government arrested Narayan Singh on October 24, 1856 at Sambalpur and sent him to jail at Raipur. In 1857 when the flame of revolution was ignited in the country, it lit sparks in the forest- region of Chhattisgarh and the people unanimously elected the imprisoned Narayan Singh as their leader. With the help of soldiers and the public, Narayan Singh escaped from the jail in

August, 1857 and reached Sonakhan.

Colonial forest policies had major impacts on the Indian forest ecosystem by deforestation for the purpose of building ships, construction and rail tracks. Before Independence, nearly 54,000 km of rail track were spread across the country and all tracks required wooden sleeper especially from the teak and sal tree. It has been estimated that nearly 15 billion US dollar value of trees were cut only for the purpose of constructing the railway track at the expanse of India’s ecosystem without having a second thought of restoration of forest, plantation

and sustainability.

Comments