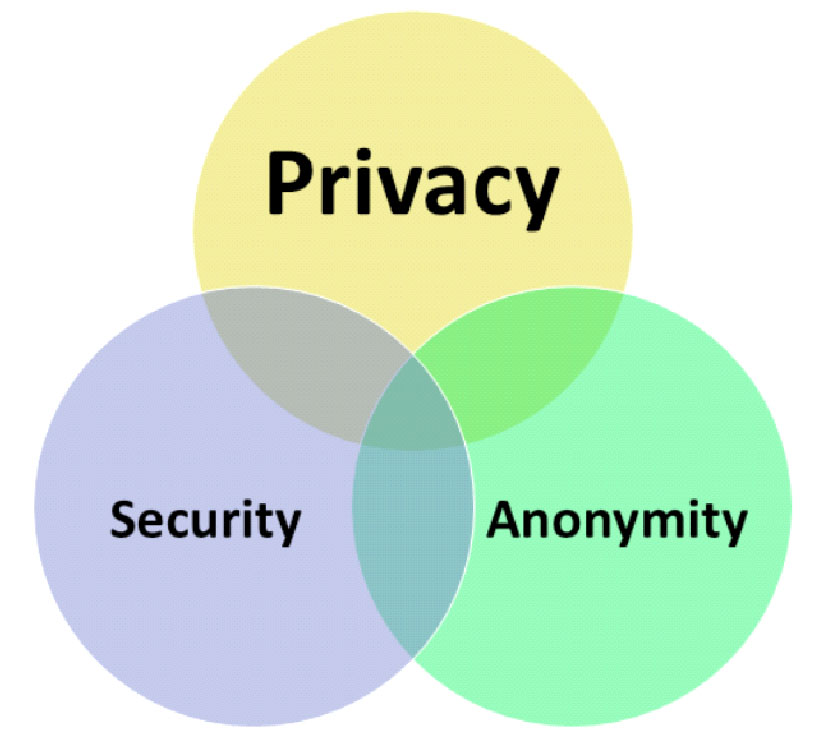

Anonymity associated with cryptocurrencies has become a worrying issue for regulators and governments. Originally dismissed as havens for criminals and money launderers, cryptocurrencies have come a long way, thanks to FinTech innovations, technological advancement and their popularity.

However, the FinTech revolution and cryptocurrency assets no longer live in their own special, independent world beyond the reach of national regulation. As many events have already shown, this market has been frequently altered by the influence of solutions, laws, forecasts, and the corrective actions of Government regulators. Today, the assertion that ‘whether or not digital money can actually become a useful and secure part of the world economy’ is being seriously debated.

Bitcoin (BTC) was created in 2009 and was the first decentralised currency. BTC has retained its status as the most valuable cryptocurrency in the world to this day. Bitcoin’s market capitalisation in January 2020 has already breached the $151 billion mark. During its record growth in Q4 2019 its capitalisation had crossed $131 billion. At the same time in January 2020, the cumulative market capitalisation of all crypto assets combined is a staggering $220 billion plus.

Such a steep jump in the value of crypto coins and tokens could hardly fail to attract the attention of world regulatory organisations, many of which took up a 'defensive position' while completely denying the obvious positive characteristics of digital money. However, a significant proportion of analysts, Government representatives, and members of the financial and other sectors remain either neutral or positive on the issue of cryptocurrency. The conflict is as evident as it is logical. Both sides and the neutrals have convincing reasons to present.

Global regulators in the international arena have an ambiguous attitude toward cryptocurrency. On the one hand, they see its potential, but on the other, they see it as ‘the latest bubble’. Many financial Moghuls see it currently more as a technology driven speculative asset class, than as a currency of transaction.

Government authorities in various regions are already actively combating the anonymity of cryptocurrencies. The Japanese regulator FSA recently pressured crypto exchanges in demanding that all ‘anonymous coins and tokens’ be delisted. This is despite the fact that cryptocurrency is entirely legal in Japan. A corresponding Indian Government dictat has been issued, effective since June 18, 2018. FSA representatives claim to see a threat to economic stability in the anonymity of cryptocurrency. Nevertheless, the regulators of many countries are gradually acknowledging the positives of digital currencies and their central banks are actively developing their own Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).

No matter how hard blockchain companies try to justify themselves, they’re often still seen as fly-by-night Ponzi schemes or vehicles for laundering money. Rightly so due to a large number of cases where private companies, exchanges & traders have been seen violating norms of the normal banking world. As a result of this, it can be extremely frustrating for legitimate startups to get genuinely world-changing ideas off the ground. Though blockchain provides inherent advantages for businesses, however, the same advantages have become a bane for governments & investors. Citizens are being cheated & Governments do not like being circumvented through.

The anonymity of cryptocurrency makes it attractive for black market and money launderers. Since the identity is not revealed, misuse is often reported yet seldom caught.

As indicated earlier, the government has not stepped up to control cryptocurrencies, but they do have the power to ban or illegalise the transactions. Yet everyone agrees that the idea of a blanket cryptocurrency ban by the Government may be naive at best. The latest news indicates that Governments may soon get along with cryptocurrencies for running their economic systems more transparently.

India Game for Digital Currency• The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) may launch its first digital currency trial programmes by December, says Governor Shaktikanta Das |

A popular scam technique used by unscrupulous criminals is the ‘initial coin offering’. A potentially legitimate investment opportunity, an initial coin offering essentially is a way for a startup cryptocurrency company to raise money from its future users. In exchange for sending active cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and Ethereum, customers are promised a discount on the new Cryptocoins.

Many initial coin offerings have turned out to be scams, with organisers engaging in cunning plots, even renting fake offices and creating fancy looking marketing materials. In 2017, a lot of hype and media coverage about cryptocurrencies fed a huge wave of initial coin offering fraud. In 2018, about 1,000 initial coin offering efforts collapsed, costing backers at least $100 million. Many of these projects had no original ideas – more than 15 per cent of them had copied ideas from other cryptocurrency efforts, or even plagiarised supporting documentation.

No matter how hard blockchain companies try to justify themselves, they’re often still seen as fly-by-night Ponzi schemes or vehicles for laundering money. Rightly so due to a large number of cases where private companies, exchanges & traders have been seen violating norms of the normal banking world

Investors looking for returns in a new technology sector are still interested in blockchains and cryptocurrencies – but should beware that they are complex systems that are new even to those who are selling them. Newcomers and relative experts alike have fallen prey to scams.

Fixing the FinTech Fad

Regulators the world over are worried about criminals who are increasingly using cryptocurrencies for illegitimate activities such as money laundering, terror funding and tax evasion. The problem is significant – even though the full scale of misuse of virtual currencies is unknown, its market value has been reported to exceed EUR 7 billion worldwide.

The existing legal framework in Europe and the USA is failing to deal with this issue. There are simply no rules unveiling the anonymity associated with cryptocurrencies. However, the tide is changing. The fifth revision of the directive on money laundering and terrorist financing by the European Parliament, AMLD5, is in the final phase of being adopted. AMLD5 includes a definition of virtual currencies and subjects virtual currency exchange services and custodian wallet providers to customer due-diligence requirements and the duty to report suspicious transactions to financial intelligence units. The information obtained can also be used by tax authorities to combat tax evasion. AMLD5’s definition of virtual currencies is sufficient to combat money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion via cryptocurrencies.

Nevertheless, it is important to closely follow up on the use cases of virtual currencies to ascertain that the definition remains to be a sufficient one going forward. When we look at the key players in cryptocurrency markets, we can see that a number of those are not included in European Parliament’s AMLD5 standard, leaving blind spots in the fight against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion. The examples are numerous and include miners, pure cryptocurrency exchanges that are not also custodian wallet providers, hardware and software wallet providers, trading platforms and Initial Coin offerings (ICOs).

Persons/businesses with malicious intent could look up these blind spots. If that would happen and it would appear to have a (material) adverse effect on the fight against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion, expanding the scope of AMLD5 should be considered. With respect to unveiling the anonymity of users in general (i.e. also outside of the context of virtual currency exchanges and custodian wallet providers), no immediate action is taken. Only in its next supranational risk assessment, the European Commission will assess a system of voluntary registration of users. This approach is not very convincing if the legislator is truly serious about unveiling the anonymity of cryptocurrency users to make the combat against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion more effective.

Brief Overview of FIU-INDIA

Governments in several countries have formed Financial Intelligence Units (FIU) to receive, process and disseminate information on money-related crimes. They function as a national centre for the receipt and analysis of suspicious transactions, information about money laundering, other related offences and financing of terrorism. FIUs in most countries have administrative and law enforcement nature. Financial Intelligence Unit works in cooperation with the international bodies like the FATF and the Egmont Group.

Persons/businesses with malicious intent could look up these blind spots. If that would happen and it would appear to have a (material) adverse effect on the fight against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion, expanding the scope of AMLD5 should be considered

Financial Intelligence Unit, The FIU- INDIA, was set up by the Indian Government in 2004 as the central national agency responsible for receiving, processing, analysing and disseminating information relating to suspect financial transactions.

FIU-IND is an independent body reporting directly to the Economic Intelligence Council (EIC) headed by the Finance Minister. The function of FIU-IND is to receive cash/suspicious transaction reports, analyze them and, as appropriate, disseminate valuable financial information to intelligence/enforcement agencies and regulatory authorities. The functions of FIU-IND are:

1. Collection of Information: Act as the central reception point for receiving Cash Transaction reports (CTRs), Cross Border Wire Transfer Reports (CBWTRs), Reports on Purchase or Sale of Immovable Property (IPRs) and Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) from various reporting entities.

2. Analysis of Information: Analyze received information to uncover patterns of transactions suggesting suspicion of money laundering and related crimes.

3. Sharing of Information: Sharing information with national intelligence/law enforcement agencies, national regulatory authorities and foreign Financial Intelligence Units.

4. Act as Central Repository: Establish and maintain national data base on cash transactions and suspicious transactions on the basis of reports received from reporting entities.

5. Coordination: Coordinate and strengthen collection and sharing of financial intelligence through an effective national, regional and global network to combat money laundering and related crimes.

Constitution of FIU-IND

The FIU–IND is a multidisciplinary body with a sanctioned strength of 74 members from various Government departments. The members are inducted from organisations, including Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), Central Board of Excise and Customs (CBEC), Reserve Bank of India (RBI), Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI), Department of Legal Affairs and Intelligence agencies.

As reflected in India’s move from a neighbourhood First policy to an Act East policy, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unequivocally wants India to assume an increased role in world affairs. Such aspirations entail more responsibilities in upholding the peace and prosperity of the world order. One such responsibility is protecting the integrity of the international economic system from illicit threats, such as corruption, money laundering, counterfeit currency smuggling, and tax evasion.

India’s International Engagement in Financial Intelligence

As economic liberalisation took hold in India in the 1990s and the pervasiveness and complexity of illicit financial threats grew, the need to engage internationally in financial intelligence arose. Only during this period did the Government of India begin developing the requisite legal mechanisms and institutional infrastructure.

Becoming a member of the International Counterintelligence Financing Regime

The 1988 United Nations (UN) Vienna Convention, which India ratified in 1990, criminalised the financing of any offenses involving the illicit production, distribution, or sale of drugs. The following year, at the G7 summit in Paris, a group of countries came together to formalise an intergovernmental body to combat money laundering. As a result, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) was established in 1989 to set standards and promote implementation of legal, regulatory, and operational measures to combat money laundering, terrorist financing, and other illicit financial threats. Thus, the international regime on anti–money laundering/counter terrorist financing (AML/CTF) came into existence.

In 1998, India officially entered the AML/CTF international regime by joining the Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG), an FATF-style body focused on implementing AML/CTF initiatives in the Asia Pacific region. As required of all APG members, the Government of India underwent a mutual evaluation of its AML/CTF efforts in 2005. This process recognises countries for meeting standard benchmarks, identifies weakness, and makes recommendations to rectify any deficiencies.

Recommendation for FIU-IND and Government of India

1. Improve domestic capacities and mechanisms for the financial intelligence apparatus. If the Government of India wants to take on global responsibilities and increase its international engagement, it must first have the capacities and mechanisms in place to do so. Reforms to its financial intelligence apparatus are thus necessary to ensure the central Government can handle this growth in its mission. To do so, Government of India needs to:

Governments in several countries have formed Financial Intelligence Units (FIU) to receive, process and disseminate information on money-related crimes. They function as a national centre for the receipt and analysis of suspicious transactions, information about money laundering, other related offences and financing of terrorism. FIUs in most countries have administrative and law enforcement nature

a. Retain a financial intelligence cadre of All India Services officers and internationally recognised experts within the bureaucracy.

b. Ensure that agencies and departments involved in financial intelligence are completely staffed to meet their missions.

c. Improve interagency coordination to ensure prosecution and successful conviction of financial crimes related to money laundering and terrorist financing.

d. Invest further in employee skill development and training as it relates to understanding cybercrime, cryptocurrencies, and financial technologies.

2. Increase international engagement on financial intelligence beyond the Asia Pacific region and Eurasia. Government of India’s international engagement has mostly been confined to the Asia Pacific region and Eurasia. For example, most of the Government of India’s MOUs on financial intelligence have been signed with Eurasian and Asia Pacific nations. Conversely, there are currently only six MOUs between FIU-IND and its FIU counterparts in Africa (Mauritius, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, and Togo) and Latin America (Brazil).

3. Promote personnel exchanges and liaisons within domestic and foreign financial intelligence agencies and departments. Personnel exchanges help build the technical capacity of an organisation. Those involved can learn different techniques and practices from the exchange agencies and departments within which they work, and bring back best practices to be implemented in their home offices.

4. Share expertise in informal banking, such as hawalas or hundis, through training and forums

5. Push for formal leadership roles within international bodies.

The Government of India’s trajectory on the international engagement of financial intelligence is quite remarkable, considering that the Indian economy has liberalised only within the last three decades. The Government of India should prioritise reforms to its financial intelligence apparatus and legal system over any desire for expanded international engagement. Enacting the recommendations above, though, requires political will, which, given the Central Government’s history of corruption, cannot be

underscored enough. However, should it follow through on these actions, the Government of India can most certainly become an international leader on this issue. Such a position can yield tangible benefits with limited costs, possibly requiring only marginally more manpower and financial resources.

However, even outside of reduction cost-benefit analysis, becoming an international leader on this issue could help the Government of India attain recognition from the international community as a rising global power. For this it is important for India to collaborate with EU’s new drafted policy AMLD5 and best practices adoption from SEC, USA to handle crimes related to cryptocurrency.

Comments