One has to think clearly, as to why Chauri Chaura and so many other events reflecting the uncompromising Swaraj notion of the patriots during the history of Freedom Movement have been denied a justified space in the pages of history projected negatively as an act of ‘unruly mob’, ‘individual heroism without a future action plan’ and ‘misguided youth’

–Dr Himanshu K Chaturvedi

History has many technical definitions but to simplify the issue, it may well be stated that history creates a specific notion in the minds of the citizens of a nation through which one positions self by understanding the saga as presented and depicted in its history books. Thus, it will not be exaggerating to suggest that historical narratives shape a thought process passed onto generations. If such misleading impressions are carried for too long, they tend to become a reality, and such historical misinterpretations tend to shape generations’ ideas. This is a well-known fact that ideological prejudice and bias are grossly responsible for deceiving our Nation’s history and individual conscience. De-colonising the minds is an uphill task, which demands not only reconstructing those events of India’s history having a broader impact on the course of the national movement but also creating a worthy space for martyrs who sacrificed themselves for the cause of the motherland. Without an iota of doubt, it would not be a hyperbolic statement that a larger canvas of the history of freedom struggle needs to be re-aligned because much has been purposely omitted, with biased objectivity. There are ample polemical misinterpreted narratives of some significant events of our history of freedom struggle leading to its political Independence since on the cultural scale colonialism failed miserably to penetrate India. Chauri Chaura needs such re-interpretation, as it can be bracketed in the list of events—neglected or grossly misinterpreted in India’s history writing after Independence and has been portrayed as a misdemeanour of an unruly mob. To suggest the issue more clearly, in an interview, Dr BB Kumar (Chairman-ICSSR, 2016) stated, ‘NCERT books, published, had political agenda, and they encouraged anarchist tendencies’. This prompts us to seek and explore more profound, as to why Prof RC Majumdar refused to be a part of history writing of the Freedom Struggle as envisaged by few top influential ideologues in Delhi in the early 1960s, because of the objective targets.

Overall, it may be observed that a sizeable number of events, to mention a few—revolutionary movement, patriots sentenced to horrible confinements of Mandalay and Kala Pani, sacrifice of martyrs for the motherland and those resisting forcefully to the barbaric practices of the colonial government in the course of the freedom movement were mostly portrayed with a negative narrative. Their names were thoroughly washed out from the pages of India’s glorious history of resistance. The event of Chauri Chaura falls under the same category. It requires serious research and reinterpretation for a sound narrative, as this event had a magnifying impact on the course of the national movement.

The question is, how should one look at Chauri Chaura?

A mere activity of an unruly mob or a nationalist act of resistance by common Indians to the colonial government or perhaps as a symbol of Swaraj uprising or a reply to Jallianwala Bagh? Unfortunately, Chauri Chaura has been portrayed as an act of unruly mob, leading to the suspension of the non-cooperation movement. Thus, it became an obstacle to nearly-achieved Swaraj! So let us start with a logical question while reinterpreting Chauri Chaura. Which event acted as a catalyst prompting the non-cooperation? Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a rude shock to the Nation after 1857, was practically repeated at Chauri Chaura, the unarmed masses were protesting peacefully against police atrocities inflicted upon locals in Chauri Chaura on February 4, 1922. Shockingly, a peaceful rally suddenly received a volley of fire leading to three innocent protesters’ martyrdom. To this, masses responded without fear and it was a direct reply to the barbaric measure of the colonial government. This led to the suspension of the non-cooperation movement. Due to retaliation by the locals, Jallianwala Bagh was not re-called at Chauri Chaura.

Reactions to the happening were prompt in the form of condemnation by the contemporary media and the Congress. This was not surprising; One may look back to the years when SV Paranjpe, editor of Kal, was barred from attending the Indian National Congress sessions because his writings were sympathetic of the Chapekar brothers. However, to understand Chauri Chaura, one needs to probe the event in four timelines or phases. Phase one of Chauri Chaura ended on February 4, 1919, and the locals were subjected to torture and atrocities by the reactionary government machinery. No account of severity hurled upon the locals after the incident in any of the primary records pertaining to Chauri Chaura. The only way to gather the account has been oral history—by meeting and interacting with the third generation of martyrs. A horror story, as gathered, is beyond imagination. At the time of this crisis, no one stood with Chauri Chaura.

The second phase of Chauri Chaura begins with the start of the Sessions Court trial at Gorakhpur. Unfortunately, before the judicial trial, the incident had already received high laurels of condemnation. As on February 9, 1922, the Gorakhpur Congress and Khilafat Committee issued a notice that people involved in the act do not deserve any sympathy and support. Before the start of the court trial, the uprising was denounced, and people connected were declared as social culprits. Needless to emphasise upon the psychological impact of such outbursts on the trial of Chauri Chaura. On January 9, 1923, the Sessions Court Judge, HE Holmes in his verdict of 430 pages passed a death sentence for 172 revolutionaries of Chauri Chaura. The second phase of Chauri Chaura ends here.

Chauri Chaura needs such re-interpretation, as it can be bracketed in the list of events—neglected or grossly misinterpreted in India’s history writing after Independence and has been portrayed as a misdemeanour of an unruly mob. To suggest the issue more clearly, in an interview, Dr BB Kumar (Chairman-ICSSR, 2016) stated, ‘NCERT books, published, had political agenda, and they encouraged anarchist tendencies’. This prompts us to seek and explore more profound, as to why Prof RC Majumdar refused to be a part of history writing of the Freedom Struggle as envisaged by few top influential ideologues in Delhi in the early 1960s, because of the objective targets

The third phase of Chauri Chaura needs attention on the ground that on this day, the list of hanged Martyrs should have been 172, not 19. So, the nationalists who came forward to stand with revolutionaries of Chauri Chaura had been already branded as socially outcast before the trial began. At this juncture, enters Baba Raghavdas, a social worker of the region and dedicated to the Nation’s cause. He was serving a jail sentence at the time of Chauri Chaura uprising due to active participation and speeches against Jallianwala Bagh. After his release, he stood firm with the people involved in Chauri Chaura by meeting their family members and assuring judicial help. The Sessions Court had given only a week to file a petition in the High Court. Baba Raghavdas contacted Motilal Nehru to argue the High Court case, but due to paucity of time, he refused. Then, Baba Raghavdas met Mahamana, Madan Mohan Malviya. Though Mahamana had left his practice long back, he was convinced that a grave injustice has been done to the revolutionaries of Chauri Chaura and acting on his conscience, Mahamana agreed to argue the case in the High Court of Allahabad. During this phase, Chauri Chaura started receiving positive support from some nationalist quarters, which could not be seen earlier. It can well be stated that this support can be symbolised in the form of Mahanama and Baba Raghavdas.

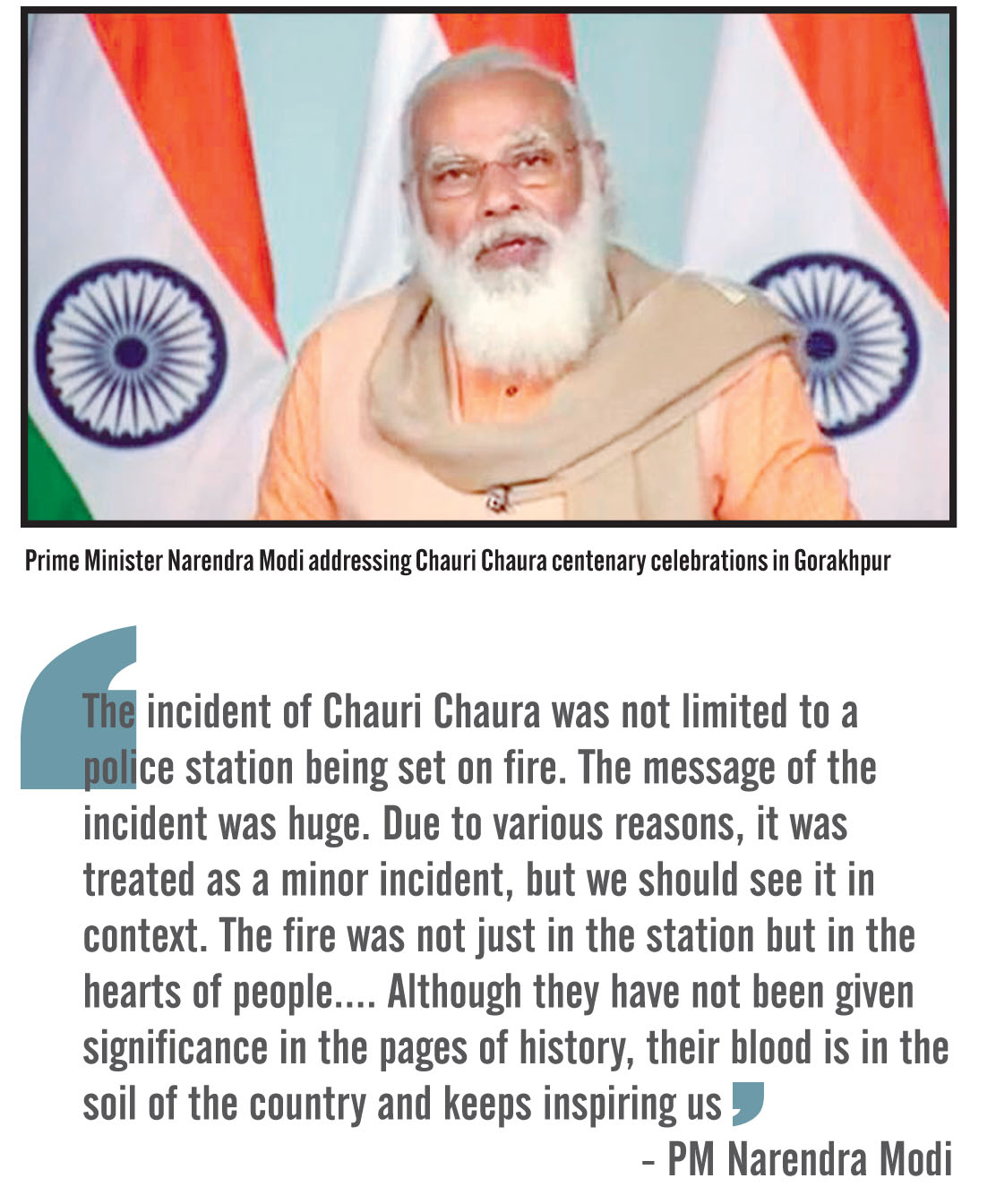

Prime Minister Modi inaugurated Chauri Chaura Centenary Celebrations at Chauri Chaura, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh and released a postal stamp (inset) dedicated tothe event via video conferencing on February 4, 2021

The fourth phase of Chauri Chaura can better be understood through the arguments of Mahanama in the High Court which established that masses at Chauri Chaura had never planned a violent attack and had no intention of burning the police station. It was a provocation by the police, leading to the martyrdom of innocent Indians that prompted the fearless reaction. It is to be noted here that after this incident, the British Government issued strict guidelines—not to fire in the air—to disrupt peaceful rallies. Above all, a comparison in the number of firing incidents by the colonial administration before and after Chauri Chaura suggests the impact that Chauri-Chura had created on the colonial rulers’ psyche. During the High Court trial, Baba Raghavdas organised and addressed a rally near Chauri Chaura police station on February 11, 1923, to lift the people’s spirits and publicly condemned the decision of the Sessions Court. Finally, the High Court reserved the judgment and ordered the hanging of 19 patriots, of which two had already passed away. The merit of the argument in the case rests upon the fact that the uprising resulted from barbaric colonial deeds. And the message that Chauri Chaura conveyed was loud and clear—no longer would Indians accept such grave misdeeds. In a nutshell, Chauri Chaura was the Indian response to Jallianwala Bagh.

Chauri Chaura can better be understood through the arguments of Madan Mohan Malaviya in the High Court which established that masses at Chauri Chaura had never planned a violent attack and had no intention of burning the police station. It was a provocation by the police, leading to the martyrdom of innocent Indians that prompted the fearless reaction

One has to think clearly, as to why Chauri Chaura and so many other events reflecting the uncompromising ‘Swaraj’ notion of the patriots during the history of Freedom Movement have been denied a justified space in the pages of history projected negatively as an act of ‘unruly mob’, ‘individual heroism without a future action plan’ and ’misguided youth’. The way these events and patriots had been interpreted by the imperialist historians is not a matter of concern. But in building a narrative of Freedom Struggle, if these uncompromising patriots have been projected as ‘unruly mob’, ‘individual heroism without a future action plan’, ‘misguided youth’ then certainly such post-Independent writings need an enquiry. This is because certain Indian post-Independent writings justify the imperialist thought process later supported by Cambridge School and Neo-traditionalist schools of thought on India’s Freedom Struggle history. One last question on Chauri Chaura would need an explanation if the uprising was not suited to a particular ideology and thus condemned, what were the political motives of a few in 1946 to rush to defend INA trials? Each one of us is aware of the ideologue and the ideology of INA. The answer is interwoven in the mood of the Nation and political compulsions of contemporary times, leading to compromise upon the theory of non-violence. It is interesting to state here that in post-Independent India, Baba Raghavdas was the first person who tried to demolish the Memorial Pillar built by the colonial government for the killed police personnels. Because of him and many others, it was a symbol of colonial savagery leading to the martyrdom of many during Chauri Chaura uprising. Ironically, up till 1990s every year, the police department held a commemorative ceremony in the memory of the killed policemen in Chauri Chaura.

(The writer is the former head, Dept. of History & Dept. of Philosophy DDU Gorakhpur University and Member-Indian Council of Historical Research-New Delhi)

Comments