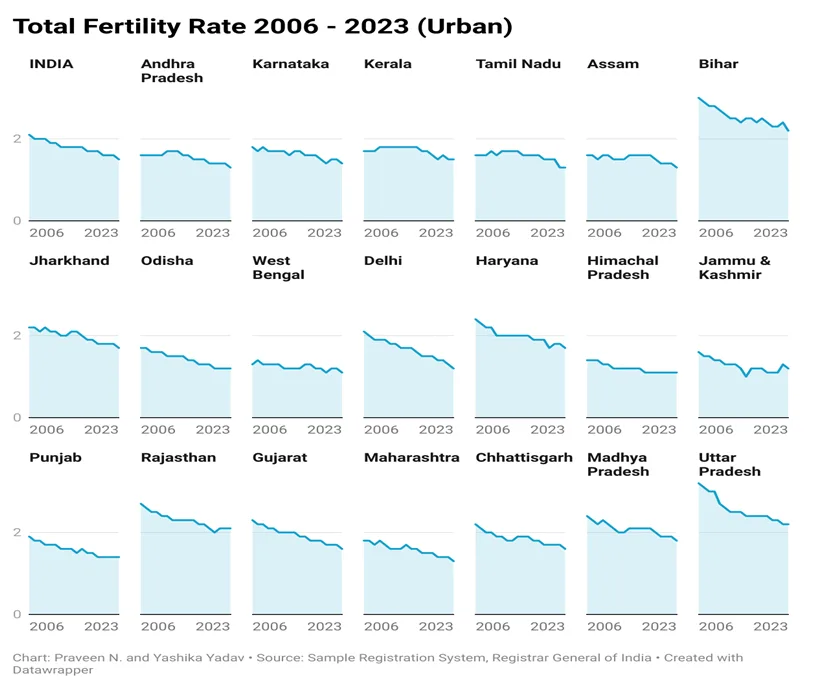

India may still be the world’s most populous country, with more than 1.4 billion people, but beneath the surface a quiet crisis is unfolding. Indians are having fewer children than ever before, and the decline is sharper and faster than almost anywhere else in the developing world. The latest Sample Registration System (SRS) 2023 report makes this plain. In urban India, fertility has already slipped below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman in 17 of 20 major states. Back in 2006, that was true of just 11 states. In rural India, 11 states are now below replacement, compared to only two then. What was once hailed as a victory for family planning is beginning to look like the start of a birth drought.

The pace of decline is striking. In Tamil Nadu, urban fertility fell from 1.8 in 2006 to 1.3 today. Kerala is now at 1.5. Odisha and West Bengal are even lower, at 1.2 and 1.1. Delhi stands at 1.2, figures closer to Tokyo than to a booming Indian capital. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh remain above replacement at 2.2, but even here change is unmistakable. Rural Bihar has dropped from 4.3 children per woman in 2006 to 2.9 today. A Chennai couple may now stop at one child, while a farmer in rural Bihar still expects three. India is living through two demographic realities at once: a fast-aging south and east, and a still-young north.

For now, the headlines still celebrate India’s population growth – overtaking China, crossing 1.4 billion. But much of this rise is momentum, the children of earlier large generations still coming of age. The real story is happening quietly: families everywhere are choosing smaller households. And that shift has happened so silently that India still talks of “population explosion” when the real story is population implosion.

Once fertility falls below replacement, history shows it rarely climbs back. Japan and South Korea have spent decades trying everything from cash payments for newborns to extended parental leave. None of it has reversed the slide. South Korea’s fertility today is just 0.7, the lowest in the world. India’s numbers suggest it may be heading in the same direction, only faster – and at a stage when it is still far from wealthy.

Why is this happening? Urbanization is part of the answer: raising children in cities is costly and space is tight. Rising education and workforce participation among women also delay marriage and childbirth. Aspirations have shifted. Where three or four children were once seen as security, today two – or even one – feels enough. Better healthcare and contraception mean families can act on these choices more decisively. What makes India unusual is how quickly these forces have converged across such a vast society. In less than a generation, the country has swung from fearing “too many children” to confronting “not enough.”

The effects are only just starting to be felt. A fall below replacement means fewer workers tomorrow, more elderly relatives to support and higher medical costs in households that already struggle. It shortens the life of the much-talked-about demographic dividend that has powered India’s growth story. Abroad, the warnings are clear. Japan has endured decades of stagnation, while South Korea is spending billions to coax couples into parenthood with little success. If India is unprepared, it could face the same fate.

For years, falling fertility was celebrated as progress. That era has ended. The question now is not how to slow growth but how to prepare for decline. The SRS 2023 report is more than a statistical update – it is a warning. India’s future will be shaped less by how many people it adds today, and more by how few children are being born for tomorrow. The birth drought may prove to be the country’s greatest challenge yet.

Comments