In the remote village of Chhasitagrah, once shadowed by rampant missionary conversions, the tribal community has taken a decisive step to reclaim its spiritual roots. Refusing to let foreign forces erode their inherited beliefs, the villagers came up with a unique form of resistance, installing a board at the village entrance that warns “crypto-converts” and missionaries carrying church messages not to enter their sacred land.

This act is not an isolated gesture of defiance; it is part of a growing movement across Chhattisgarh’s Kanker district. From Kudal village in Bhanupratappur block to many other hamlets, tribal gram sabhas are asserting their constitutional and traditional rights, refusing entry to pastors and missionaries involved in conversion activities.

The message on the boards is clear and uncompromising, ‘Those who seek to change our faith are not welcome here.’

What began as a local stand in a few villages has now become a symbol of indigenous pride and unity. Tribals are not only resisting external pressures but also reviving the rituals, festivals, and spiritual practices that define their identity. This World Indigenous Day, let us tell you the story of the people of Chhasitagrah and other tribal settlements, reminding the world that faith, when rooted in centuries-old traditions, can stand firm against even the most persistent attempts at erasure.

A resistance worth celebrating

Villagers have put up defiant warning boards at the entrances of the village, announcing that Christian missionaries, pastors, or outsiders who are involved in religious conversion activities are not welcome. The message is forthright and supported by legal rights under Schedule V of the Constitution and the PESA Act, 1996, which gives tribal gram sabhas the power to safeguard their culture, tradition, and spiritual practices.

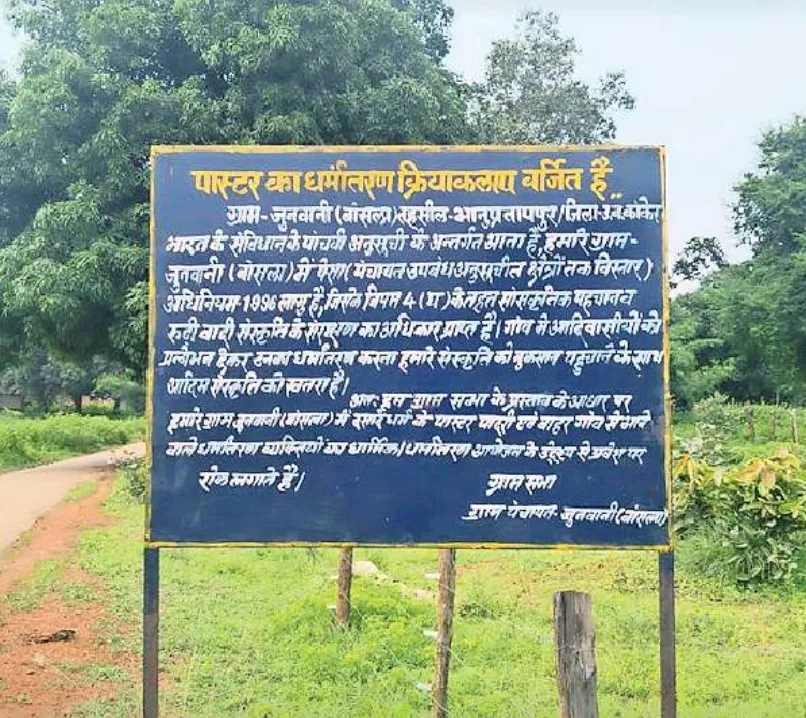

The board installed in the village says:

“According to the PESA Act and Schedule V regulations, foreigners engaged in conversion activities such as pastors and missionaries, are prohibited from entering this village. The Gram Sabha has the right to save and conserve tribal tradition and culture.”

This phenomenon is not new. Following Kudal, similar boards have come up in some other villages like Madhya Pradesh’s Janakpur, Parwi, and Junwani. In Junwani village, where eight families had recently converted to Christianity and three of them have since reconverted, villagers gathered to deny outside religious encroachment ceremonially. “We don’t dislike any religion,” said Rajendra Korram, a Junwani villager. “But we sharply disagree with deceptive conversions that involve trapping our poor tribal brothers with deceitful assurances and money rewards.

Tensions came to a boiling point in Kudal a week ago when a buried ritual at the death of a converted tribal woman precipitated a fight over funeral customs, engendering villagers’ outrage. The episode prompted the Gram Sabha to approve an official resolution forbidding pastors and converted outsiders from holding or attending any religious functions in the village.

PESA as a protective shield

The foundation of this resistance is the constitutional legal infrastructure of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act (PESA), which entrusts tribal Gram Sabhas with the right to protect their traditions and ban exploitative practices, including religious conversion by tempting or pressurising people. Tribal Development Committee District Vice President Gyan Singh Gaur reiterated that these moves are completely constitutional according to the Fifth Schedule. “The law is on our side.”. The PESA Act gives power to our Gram Sabhas to make decisions in order to safeguard our indigenous faith and culture,” he asserted.

In a state where the tribal population is targeted through clandestine networks of conversion, these villages are becoming great symbols of resistance. The tribal people are no longer mute; rather, they are claiming their rights with courage and clarity.

Second village to follow suit

Junwani was the second village, following Kudal to officially curb missionary work. Reportedly, five Christian families in Junwani remain so, even after attempts to bring them back to the tribal fold. Concerned that their cultural values were being eroded, the village has put up boards citing the PESA Act, specifically cautioning against missionary intrusion.

These warning boards are not just signs. They are a statement of purpose by tribal communities committed to upholding their cultural independence. The boards are large and reference constitutional provisions, leaving no doubt of the villagers’ determination.

Grassroots rejection of religious manipulation

Across the tribal heartland of Chhattisgarh, the story is often one of loss, village after village slowly slipping under the grip of missionary conversions. In many pockets, the change has been so gradual that it went unnoticed at first: an abandoned ritual here, a forgotten festival there. But over the years, the erosion has become visible. Age-old customs, ancestral worship, and the dharmic practices that defined tribal life for centuries are being replaced with unfamiliar prayers and foreign symbols.

Yet, in this bleak landscape, there are sparks of hope, stories that prove communities can still rise, resist, and reclaim what is theirs. The recent stand taken in Chhasitagrah, and now echoed in village after village across Kanker district, is one such story.

This is not a movement orchestrated by political forces or outside organisations. It is a grassroots rebellion born of lived experience. Villagers recall how those who converted often turned away from community life, refusing to take part in harvest festivals or ancestral rites. In common parlance, such converts came to be spoken of as “agents of evil” not out of casual insult, but out of deep hurt at seeing the moral and social fabric of their society fray.

For these tribal societies, faith is not just personal belief; it is the foundation of their unity. Conversion, they say, does more than change religion, it splinters the very sense of belonging, replacing collective life with division and suspicion. The breakdown has been both moral and social, threatening the shared identity that binds the village together.

Now, in defiance, communities are taking matters into their own hands. Gram Sabhas have passed formal resolutions declaring that missionaries and pastors involved in conversion activities are not welcome. Boards with bold warnings are being placed at the entrances of villages, telling outsiders in no uncertain terms to keep away. These boards are not just pieces of painted wood; they are symbols of a people reclaiming their agency.

In this movement, there is no waiting for saviours, no appeal for external rescue. It is the people themselves, farmers, herders, elders, and youth, who are standing up, their resolve shaped by years of watching their way of life erode. They are not only resisting the present threat but also rekindling the festivals, songs, and spiritual practices that had begun to fade.

The tribal stronghold of Chhattisgarh is stirring. No longer passive targets of an organised conversion campaign, these communities are awakening as mindful guardians of their dharmic heritage. The hope is that each new board, each new resolution, will inspire another village to stand up. And perhaps, one day soon, the tide will turn from slow loss to steady reclamation.

Comments