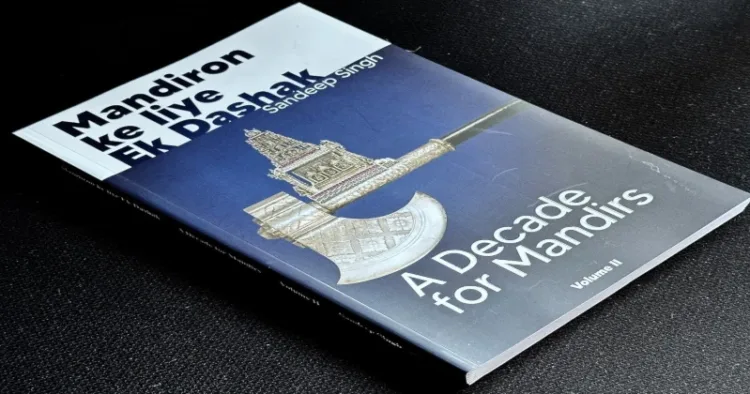

This book is a continuation of Temple Economics Volume I by Sandeep Singh.

Although he explained in detail how Bharat is losing Mandirs in Volume I itself, talking solely is not the solution to fighting the obstacles to reclaiming the mandirs, particularly in this secular era. Hence, the author addresses actionable solutions for the same cause.

So, to have durable, pragmatic, and practical solutions, the author starts this book boldly addressing the deep-seated ‘anti-mandir bias’ in the entire ecosystem and also pays attention to this blazing issue of ‘how Bharat is losing Mandirs’ again when we are completely ‘free’. ( Are we?)

The author started with the instance of Kalighat Mandir and described how it suffered from imperial—colonial forces. A ‘tarksheel’ (logical) Hindu will agree with the author when he emphasises that bringing the internal affairs of the mandir to the court is a huge blunder for the future of the Mandirs of Bharat.

Describing the preconceived notion of people about the authority of the mandir, the author points out – “The practice of modernising mandirs through reducing the authority in them and thereby, wealth of Brahmins has been going on since the late eighteenth century. The default assumption in Bharat today is that unless a mandir is inside a person’s home or there is evidence that it was founded as a private endowment, The public — either through state bodies or as individual citizens — have the right and even the responsibility to determine what goes on at Hindu mandirs.”

While analysing the bias and colonial mindset of the Indian Judiciary, Singh says –

“Once the pujaris went to the court, the judges and the Sarkari Hindus became the new pujaris. They started dictating the functioning of mandirs, not only those that went to them with their dispute but also of all the mandirs. Their interest was more in the money in the mandir than on pending cases in the courts.”

The author wants us to realise the fact that the government’s control over Hindu temples must be a point of apprehension and anguish for many Hindus. However, it is there; it has not reached a critical mass to spark widespread awareness and drive meaningful reform.

As we have that colonial mentality of accepting our appreciation from white faces to appeal to Laymen, the author cleverly decides to present the whole issue in the next unit through the lens of a foreigner; the author presents the perspective of a non-Hindu—Deonnie Moodie—to get a better understanding of this entire matter.

Even history students go through many books where a foreigner understands and appreciates Bharat better than a Hindu. From this perception, this book proves more useful to the students of social sciences.

Singh, in the next unit, breaks the wrong constructs formulated by either ‘colonial masters’ or the lack of adhyayan by Hindus. For instance, in the context of desh, we have misunderstood ‘In’ia’ as a name for Bharat. Further he breaks the wrong construct around panchatantra’s much talked shlok at every Hindu seminar i.e. ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’. The author explains that we’ve accepted the wrong vision of the entire statement.

Moreover, the author delves into the ramifications of these detrimental constructs of Hindu society by emphasising the verity that not reading our scriptures is the biggest fault line of present Hindu Society. The author points out that although there is much comprehension regarding identifying the enemies within, not identifying enemies and their tactics properly will eventually harm our Hindu society. In Part III, Singh identifies various enemies, encompassing political Hindus, governmental Hindus, intentional enemies, and unintentional enemies. Like the previous volume, he presents these ideas through recent case studies.

In the present ideological warfare, Hindus need to be proactive rather than defensive on several issues, and the author in part IV suggests certain ways to do this. But first, Hindus should demand the reclaiming of temples along with the restoration of the murtis and arrange legal support for this cause.

The author gives several solutions for restoring mandirs to their glory, such as deity’s rights, respecting the pujaris, reviving utsav fairs, cleaning Mandirs, reclaiming literature, reestablishing Mandirs as a centre of socio-economic activities and building new Mandirs.

The insights provided by Sandeep Singh in this volume of Temple Economics are not just a wake-up call but a roadmap for action for all Hindus. The author is currently working on the third volume. After delving into these eye-opening first two volumes, which address the critical issue of Hindu Mandirs, readers will surely wait for the next instalment.

Comments