Last month, the Taliban’s Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, while attending a public program, said that there is an absence of an official border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. He further said that Afghanistan will never recognise the Durand Line as its official border with Pakistan. In the past also, senior Taliban leaders have questioned the legitimacy of the Durand Line like – Defence Minister Maulvi Muhammad Yaqub Mujahid last year said that the Durand Line is merely a ‘line’. Maulvi Yaqub also said that Afghanistan will raise the matter with Islamabad when the Afghan people want it. Since the Taliban came to power in Kabul, troops on both sides of the disputed border have fired at each other on numerous occasions, causing casualties on both sides. This border dispute is not new; it emerged soon after the creation of Pakistan. When Pakistan joined the United Nations in 1947, Afghanistan was the only member nation to vote against its membership. Afghans argued that Pakistan should not be recognised as long as the problem of the disputed border remained unresolved. It would be right to say that the Durand Line issue has continued to complicate the unpredictable nature of the Afghan-Pakistani relationship since the birth of Pakistan.

Let’s have a quick look at the origin of this controversial borderline. The growing imperial Russian expansionism and influence in Central Asia during the nineteenth century increased the anxiety of British authorities in India. This resulted in many political and diplomatic confrontations between the two Empires, which later became known as “The Great Game”. The construction of the Trans-Caspian railway, particularly the extension built in 1890, that reached the Afghan border at Goshgy was a further source of concern for the British Raj (Government of India), as it may enable Russia to bring large forces to Afghanistan. Russia was fearful of British commercial and military raids into Central Asia, while Britain was worried about Russia adding the ‘jewel in the crown’, India, to its vast territory. As a result, an atmosphere of suspicion, distrust, and permanent fear of war between the two Empires emerged. To address this issue, Britishers initiated the military campaigns against Afghanistan, famously known as the Anglo-Afghan wars. However, they failed to impose direct control over Afghanistan. So, they settled the issue by turning the country into a buffer state. To fulfil that plan, the British government supplied the Afghan Amir (King) Abdur Rahman Khan with military weapons and equipment to defend Afghan northern areas from Russian influence.

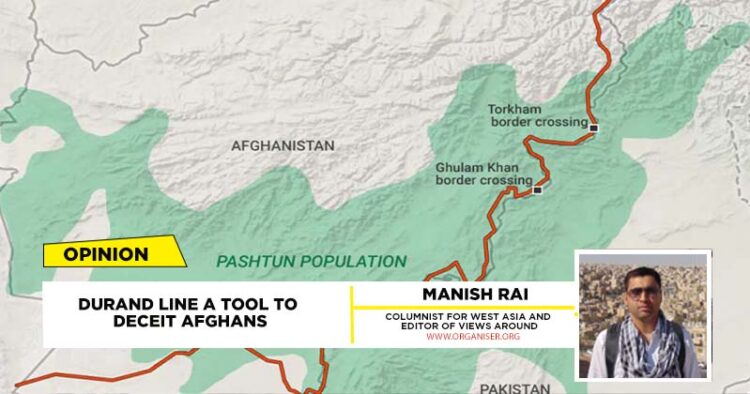

But, as this strategy was not secure or promising enough, also as part of their desire to control Afghan foreign policy, the British believed it was of vital importance to define Afghanistan’s external borders. But, before going for any formal border agreement, the British aimed to annex as much territory as possible to meet their economic, geopolitical, and strategic needs. This stripped Afghanistan from most of its land and left it with weaker administrative control over what was remaining. After enough land grab was done then, Sir Mortimer Durand, the government of India’s foreign secretary, arrived in Kabul on October 2, 1893, to start negotiations with the Amir of Afghanistan on demarcating the border of Afghanistan. Ultimately, negotiations resulted in the creation of the Durand Line, which divided half of a Pashtun population intimately related by culture, history, and blood. But the Durand line never served as a de facto border. After signing the agreement, Sir Durand himself said: “The tribes on the Indian side are not to be considered as within British territory. They are simply under our influence in the technical sense of the term, that is to say, so far as the Amir is concerned and as far as they submit to our influence, or we exert it”. This was further clarified when the Viceroy, Lord Elgin, writing in 1896, said: “The Durand Line was an agreement to define the respective spheres of influence of the British Government and the Amir. Its object was to preserve and to obtain Amir’s acceptance of the status quo”.

The argument of every successive Afghan Government is that this line is not a legitimate border since it was intended to be merely a line of control, which, for the sake of security, divided the area into zones of influence. Another assertion on behalf of Kabul, which disclaims the legitimacy of the frontier, is that the border agreement was signed under duress. Although, many historians provide proof that Amir was fully aware of the content and the consequences of the agreement. But, one should not fail to admit that Amir was forced to sign it under the threat of an economic embargo. Furthermore, Abdur Rahman Khan wanted to avoid war between Britain and Russia on his territory, which would have inevitably had disastrous consequences for Afghanistan. The country had little space for negotiations when facing the pressure of a global superpower of that time, i.e., Britain.

Afghan authorities always asked their British counterparts for comprehensive talks to sort out this border dispute, but all the requests went unheard. And as Britain prepared to leave India, Afghanistan again demanded a revision of the border. Its request was denied. Subsequently, Afghanistan announced that all previous Durand Line agreements, including the prior Anglo-Afghan treaties upholding it, are null and void. Moreover, the Afghan parliament issued a resolution denouncing the Durand Line as a fraudulently drawn international border in 1949. To summarise, it would be right to say that no Afghan Government or political party has ever accepted the Durand line as the international border with Pakistan. But as Afghanistan became a war-torn country in the late 1970’s, this border dispute was not pursued seriously by Afghans as they were too busy fighting among themselves.

This was an idle condition for Pakistan to increase its sphere of influence in Afghanistan and even termed it as the fifth province of Islamabad. Pakistan has never been willing to risk a dynamic and powerful Afghan state controlling its affairs. As stable and secured, Afghanistan won’t let Pakistan interfere in its domestic issues and will denounce the current border line with Islamabad. Pakistan must acknowledge that the Durand line is not a settled issue, and they can’t proclaim anything unilaterally. The Durand line dispute is not merely a dispute over an international border but of identity, ethnicities, and sovereignty for Afghans. Unless the two states reach a consensus on the aforementioned affairs, this controversial and contested borderline will continue to spew enmity into both sides.

Comments