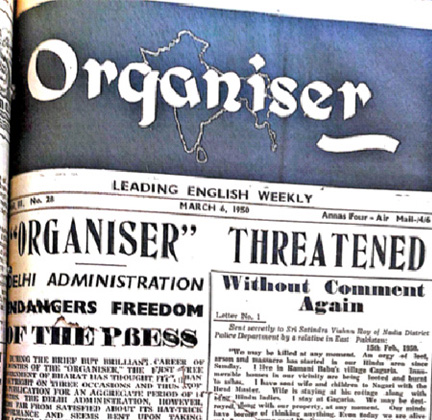

The RSS, a Hindu right-wing group, ran (and continues to do so) an English weekly in Delhi called the Organiser. Brij Bhushan was its printer and publisher while KR Malkani was its editor. On March 2, 1950, the chief commissioner of Delhi imposed a prior restraint on the Organiser under Section 7(1)(c) of the East Punjab Public Safety Act, 1949 which extended to Delhi as well. Under this provision, a provincial government was authorised, for protecting ‘public safety’ and ‘public order’, to require a newspaper to submit the newspaper for scrutiny before publication. This was akin to the prior restraints which had been imposed on the press in 1799 by Governor-General Wellesley during the Fourth Mysore War, and under the Defence of India Rules, 1939 at the time of the Second World War. The government’s order imposing the restraint stated that the Organiser was ‘publishing highly objectionable matter constituting a threat to public law and order’. Its printer, publisher and editor were required to ‘submit for scrutiny… all communal matter and news and views about Pakistan including photographs and cartoons…’ Once again, by a majority of 5-1, the court struck down the chief commissioner’s order.

However, the court essentially held that a prior restraint is permissible under the Constitution, so long as the restraint is imposed in furtherance of any of the enumerated exceptions to free speech under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. he sole Muslim judge on the court at the time, Justice Fazl Ali, dissented once again. He agreed that the term ‘public order’ was wide enough to cover even ‘a small riot or an affray’, but held that in some cases ‘even public disorders of comparatively small dimensions may have far-reaching effects on the security of the State.’ He noted that Delhi had been declared a dangerously disturbed area’ at this time, an obvious reference to Hindu-Muslim riots, justifying a law of this nature. In short, the Romesh Thapar and Brij Bhushan cases had farreaching implications for the manner in which the government could restrict speech which was designed to incite Hindu-Muslim riots and killings. The court’s judgments could be read to mean that not every local Hindu-Muslim riot or mass murder was capable of threatening the security or existence of the Indian State. Consequently, the government would be powerless to restrain hate speech which was designed to incite such local disturbances, which were nonetheless deeply troublesome. The Supreme Court’s decisions were then followed and applied in several high courts throughout the country.

(Excerpts from Republic of Rhetoric: Free Speech and the Constitution of India by Abhinav Chandrachud, published by Penguin Books)

Comments