In the field of computational astrophysics, scientists have unveiled a method allowing more realistic simulations of stellar atmospheres. This breakthrough opens the door to accurate modelling of stellar spectra, the key tool astronomers use to decode the conditions inside stars, the structure of circumstellar disks and the chemistry of interstellar clouds.

The atmosphere of a star including our Sun is heterogeneous in nature. It is a non-uniform mixture of neutral and ionized matter, constantly interacting with a diffuse radiation field. This dynamic interaction involves numerous physical processes that shape matter and radiation.

It may seem easy to compute these interactions if we assume the system is in equilibrium. But stars are turbulent environments and equilibrium is more the exception than the rule. This makes the task of accurately simulating stellar atmospheres enormously complicated.

Scientists have been tried to simplify the problem. Most of the existing models used a key assumption that atoms could shift away from equilibrium in their energy states, their motion, represented by velocity distributions to follow the Maxwellian curve, which describes the particles are in equilibrium. This assumption made calculations manageable, but it comes at a cost. The atoms are short-lived excited states rarely obey this tidy pattern.

In reality, stellar atmospheres are chaotic in nature. Photons scatter in all directions, energy levels fluctuate and atomic velocities often defy equilibrium rules. Capturing this complexity requires what astrophysicists call full non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (FNLTE) radiative transfer, this problem was first identified in the 1980s but left unsolved due to overwhelming computational demands.

The Challenge of FNLTE

FNLTE modelling allows everything to vary including the number of atoms in each energy state, its velocity distribution and the radiation field. The challenge lies with these variables, that are all interdependent and forming a complex web of equations. That even the most advanced computers struggled to crack this puzzle.

Now a progress for these complex equations has been made. A researcher at the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), Bengaluru, working with collaborators from IRAP Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie, Toulouse, France to make remarkable and significant steps forward.

The first breakthrough came when the team tackled a simplified version of the FNLTE problem: the case of a two-level atom, where an atom could jump only between two energy states. While this was a conceptual advancement, stellar atmospheres’ objective complexity lies in the atoms with more than two levels.

The new advance is the successful solution of the three-level atom problem. With three energy levels new scattering pattern emerges, including Raman scattering, where an atom absorbs light at one frequency and re-emits it at another. Traditional models could only approximate such processes. However, the new FNLTE framework captures them naturally.

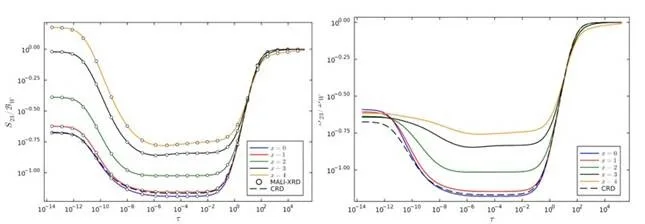

Figures generated by the study illustrate just how different the results are. The source function plotted against optical depth in the new model diverges sharply from standard approximations, demonstrating the impact of including realistic conditions.

A New Picture of Stellar Surfaces

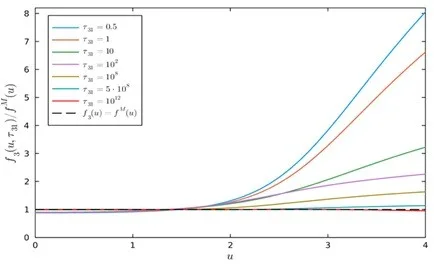

The most striking finding came when the researchers compared velocity distribution so FNLTE with traditional models, excited hydrogen atoms neatly followed the Maxwellian curve in traditional model and in the FNLTE framework the distribution showed significant deviation, particularly near the surface of stellar atmospheres. This is a critical discovery because the outer layers of stars are where astronomers collect the spectral fingerprints used to decode stellar properties.

With this advance method, astrophysicists can simulate stellar spectra with a realism never possible before. Most accurate models can refine our measurements of stellar temperatures and compositions, improve our understanding of circumstellar disks and molecular clouds where planets are born and push forward the search for the Earth-like exoplanets, which relies on detecting faint planetary signatures hidden in the light of their host stars.

“The major conceptual jump from two to three or more atomic levels has now been made,” said Sampoorna M from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST). The team comprising of T. Lagache and F. Paletou from IRAP, Toulouse and M. Sampoorna from IIA, Bengaluru are now pushing ahead. They aim to generalize the method for even more complex atoms and to design faster numerical techniques to manage the heavy computational load.

The Broader Impact on Astrophysics

This achievement is more than just a technical milestone. By capturing the chaotic reality of stellar atmospheres, scientists can move beyond simplified models and explore astrophysical processes with greater accuracy. This means stellar physics will have a clearer understanding of temperature variations, elemental abundances and the dynamics of stars. Better insights into the physics of circumstellar disks and molecular clouds, where planets like Earth take shape and the Exoplanet Discovery is a more reliable detection of subtle starlight distortions hinting at the presence of orbiting planets.

With advances in supercomputing and numerical optimization helps to bridge the gap. The approach expands to multi-level atoms, it may eventually form the basis of a new standard in stellar modelling, a foundation on which future space telescopes and astrophysical research can build.

The finding from simplified assumptions to an entirely realistic picture of stellar atmospheres mirrors the broader journey of science itself by pushing past approximations, understanding complexity and unlocking hidden truths.

Collaborating expertise from India and France in this research problem is not just a step forward in astrophysics, but also a demonstration of international collaboration to driving discovery of exoplanets. As scientists refine these models, our view of stars, planets and the cosmos advances and more accurate than ever before.

Comments