There was a time when the very mention of a ‘trade union’ instantly evoked the image of Communists, for Communist trade unions, long dominant in the Bharatiya labour sector, had infused a distinctly adversarial ideology into it.

Communist Citadel

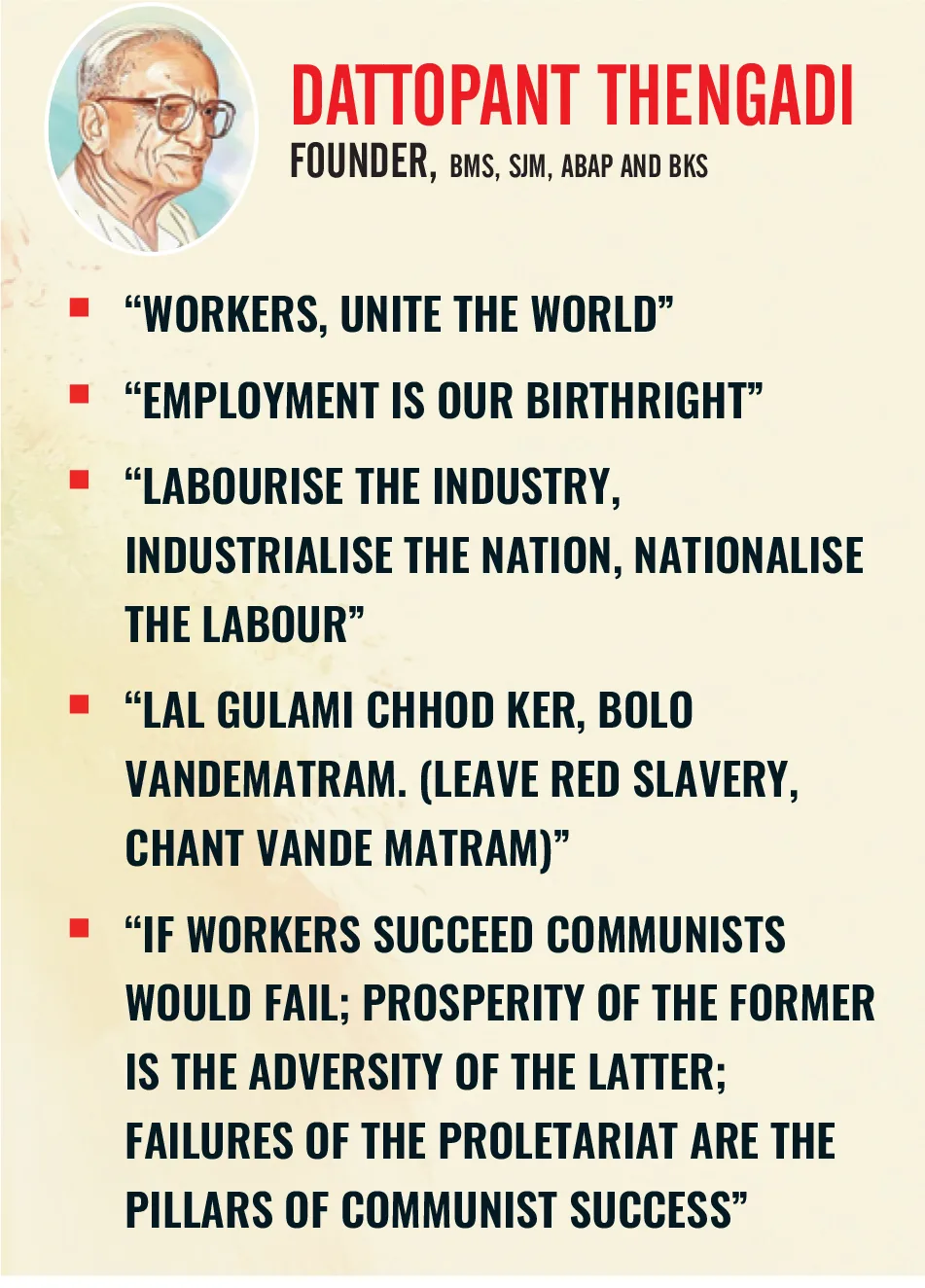

Although the Congress leadership founded the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), its leaders had little time or inclination for trade union affairs. By the time India attained Independence, the Congress found that while it had consolidated control over almost every sphere of national life, one important domain, the trade union movement, had passed entirely into Communist control. INTUC, thus formed, too, remained influenced by the same ideological foundations as AITUC. Thus, the entire worker mindset had come to be grounded in the Communist doctrine of class struggle. This situation prevailed until Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) was founded in 1955 by Shri Dattopant Thengadi, marking the beginning of a gradual but profound transformation in the Indian labour movement. Thengadiji provided BMS with a strong and distinct ideological foundation rooted in Bharatiya thought.

Class Division Led to Rampant strikes

From its inception, AITUC propagated the belief that employers and employees belonged to inherently antagonistic classes locked in inevitable conflict. Consequently, strikes, agitations, and confrontations became the accepted means of redress. This conflict-based approach, cultivated under British rule, also shaped Bharat’s early labour legislation. The very title of the foundational law, the Industrial Disputes Act, reflects the perception of labour laws as conflict resolution tools. Employers, too, became victims of the same mindset. They began to view labour merely as a factor of production or a purchasable commodity, and sought profits by exploiting it. This grim situation persisted well into the late 1980s. The turning point came with the verification held in 1989, when BMS emerged as the largest Central Trade Union in the country under the able guidance of Thengadiji.

Thengadiji decisively countered the theory of antagonistic industrial relations by proposing an alternative rooted in Bharatiya ethos, the concept of Udyog Parivar, or the “Industrial Family.” This vision sought to replace both the Western ‘master–servant’ model and the Communist doctrine of class struggle. BMS, along with many nationalists, even proposed that the ‘Industrial Disputes Act’ be renamed as the ‘Industrial Relations Act’, reflecting a more harmonious approach.

Changing the Mindset

The greatest challenge before BMS, however, was the psychological mindset of the general workers, their ingrained perception of employers as their natural adversaries; while employers regarded trade unions as constant irritants, yearning for ‘union-free’ workplaces. Changing this mindset was an uphill, tremendous task that slowed the acceptance of the Udyog Parivar ideal.

Adhering to “Work is Worship” Philosophy

In the process, Bharat lost its traditional spirit of ‘work culture’, eroded by mutual distrust between the two important stakeholders: the employer and the worker. Meanwhile, nations like Japan surged to the forefront by nurturing an ideal work culture. With profound insight into the Indian ethos, Thengadiji revived the eternal ideal of labour: “Work is Worship.” Through this, he reawakened the timeless value system upon which the nation stands.

Karl Marx had declared, “The proletariat has no fatherland.” Thengadiji observed that Communist nations across the world had nationalised Marxism by adapting it to their respective cultural and traditional contexts. Indian Communists, however, clung rigidly and mechanically to Marx’s literal words. As a result, when the nation faced a crisis on many occasions, AITUC prompted the workers to act in anti-national ways, a fact well documented in history. AITUC wielded great influence, particularly among salaried employees in sectors like Banking, Defence, and Postal services. During the year 1942, it betrayed the nation by working against the Quit India Movement through a covert alliance with the British. Again, in 1962, during the Chinese aggression, AITUC, following directives from its political bosses, sided with China and even refused to donate blood for wounded Indian soldiers. During the Emergency of 1975-1977, AITUC supported the autocratic rule of Indira Gandhi, aligning itself with its political master, the CPI. This tendency of Communist unions persisted thereafter.

Such a deplorable state of affairs compelled Dattopant Thengadi to proclaim “Nationalise the Labour” as the foremost priority of the labour movement. In stark contrast to Communist unions, BMS stood steadfastly with the soldiers and the Government during the wars of 1962, 1965, and 1971, as well as during subsequent border crises. For this purpose, BMS formed the Rashtriya Mazdoor Morcha, an alliance of like-minded trade unions. The erstwhile slogan of Inquilab Zindabad gradually gave way to a new invocation in the labour sector, Bharat Mata ki Jai!

From his deep study of trade union history, Thengadiji concluded that political fragmentation had long weakened the Bharatiya labour movement. Hence, he resolved that BMS would remain strictly non-political, or more precisely, ‘apolitical’. He even declined the offer to join the Janata Party Government in 1977. Extending this idea, he formulated the doctrine of “responsive cooperation,” meaning that BMS’s cooperation or non-cooperation with the Government or employers would depend upon their respective attitudes toward workers.

Sri Guruji shaped BMS

Thengadiji’s ideological foundations were frequently refined through the guidance of Sri Guruji or MS Golwalkar, whose insights profoundly shaped the course of the BMS. When Capitalism vested surplus labour in the hands of employers, and Communism placed it under the State, Sri Guruji observed that, for Hindus, “the surplus value of labour belongs to the Nation.” Inspired by this profound insight, Thengadiji infused the integral vision of Bharatiya thought into the labour movement. He evolved a cyclic and holistic concept for BMS: “Rāstra Hita, Udyoga Hita, and Mazdoor Hita”, signifying that the interests of all three stakeholders, i.e., “the nation, the industry, and the labour” must be harmoniously safeguarded. He also insisted that every industrial settlement between employer and employee must take into account the interests of the consumer as well, thus completing the ethical circle of industrial relations. In his memorable address at the Thane Meet of 1973, shortly before his passing, Sri Guruji further remarked: “Labour is also one form of capital in every industry. The labour of every worker should be evaluated in terms of share, and workers raised to the status of shareholders.”

While AITUC, INTUC, and other trade unions drew their inspiration from the untoward and violent labour incident in Chicago a century ago and observed May Day as Labour Day, Thengadiji sought to Indianise the very concept of Labour Day. He reminded that May Day commemorates not an inspiring saga but the failure of the trade union movement in America due to the Left’s violent and divisive methods. In its place, he proposed Vishwakarma Jayanti as ‘National Labour Day’. In ancient Bharat, labour was accorded a dignified position. Vishwakarma, the Acharya of labour and the legendary inventor of numerous vocations, was exalted to divine status as the Indian icon of the dignity of labour.

No Compromise on Fundamentals

The Communist and Congress-affiliated trade unions had reduced the movement to a culture of ‘bread and butter trade unionism’, where the demands for material gains became the sole objective. Thengadiji, however, called upon its activists to rise above mere material gains and adopt the ideal of “Tyāg, Tapasyā aur Balidān” – sufferings, dedication, and sacrifice. Only through such dedication, he said, could the Indian worker attain true heights. The extraordinary success of BMS rested on two pillars: first, the inspiration and organisational culture derived from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh; and second, Thengadiji’s unwavering adherence to the ideal of “no compromise on fundamentals”. One common thread that runs through all the organisations and personalities shaped by him is an unbending resolve never to compromise on core principles, even in the most testing times.

Course Correction by Thengadiji

Thengadiji was equally committed to improving the economic condition of workers, making adequate wages a priority item on the trade union agenda. He gave a clarion call: “Desh ke hit mein karenge kām, kām ke lenge pūre dām” – “We shall work for the interest of the nation, yet take the full and rightful wage for our labour.” He formulated policies and practical solutions to many pressing labour issues, such as correcting the anomalies in the Consumer Price Index, recognising the bonus as deferred wages, and drafting the National Charter of Demands, which was submitted to President VV Giri. He opposed labour-displacing computerisation (not the computers per se). His brilliant ideas on labour, included in his submission to the First National Commission on Labour, were later published as a seminal book titled Labour Policy (Shramnīti in Hindi). He also guided the sole BMS representative in the Second National Commission on Labour while submitting a dissenting note on some controversial issues.

Exhorting Workers to be in solidarity with Humanity

At the international level, while Communists romanticised the working world with the slogan “workers of the world, unite,” to prepare them for class war and the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” Thengadiji amazed everyone by presenting a nobler and more appealing call: “Workers, unite the world.” This single phrase reminds workers of their higher mission – humanity’s solidarity.

Always ahead of his time, Thengadiji founded the Sarva Panth Samadar Manch (Forum for Respecting All Faiths) and the Paryāvaran Manch (Environmental Forum) within BMS, and also established the Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, with BMS as one of its integral components from the very beginning. Thengadiji also proposed functional representation in elected bodies in the democratic set-up, ensuring that various sectors of national life find expression in governance. He outlined guidelines for a future socio-economic order, which formed the foundation of BMS’s long-term vision. Through all these endeavours, Thengadiji, the Acharya of the Bharatiya trade union movement, engraved indelible imprints in the annals of labour history. His mission to Indianise the labour movement polluted by Leftist ideologies was akin to Bhagirath’s divine effort to bring the Ganga to Earth for the redemption of the forefathers. Yet, many Western notions still need to be deconstructed and reinterpreted in the light of Bharatiya wisdom. His last message, delivered at the Surat Baithak, was: “In the future, we shall need intense tapasya to face the new challenges.”

In his visionary book Third Way, Thengadiji reminded us that “the final phase of ideological warfare” has come. When globally both communalism and capitalism are facing a crisis, the task against ideological warfare should be carried forward by lakhs of BMS activists. Drawing inspiration from Thengadiji life and teachings, they should internationalise Bharatiya labour movement.

Comments