When the frozen silence of Ladakh cracked into slogans of protest this year, India confronted more than a local political crisis—it faced a strategic riddle. Environmentalist Sonam Wangchuk’s hunger strike, rapidly turned into Ladakh’s bloodiest unrest since independence. Four lives lost, dozens injured and a century-old calm shattered. Behind these protests lies a pressing question:

Should Ladakh be granted statehood and inclusion under the Sixth Schedule—or should the Union Territory remain under central stewardship to safeguard India’s northern frontier?

The mirage of autonomy

In 2019, when Article 370 was abrogated and Ladakh became a separate Union Territory, Leh’s streets erupted in celebration. The dream was of direct governance and equitable development. But six years later, the same streets echo with disillusionment.

The Leh Apex Body (LAB) and Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA) are demanding statehood, Sixth Schedule status, and their own Public Service Commission. Their complaint: political marginalisation and loss of control over land, jobs, and culture. It can be understood, “autonomy” for a strategically sensitive region can create dual power centres, slowing decisions vital to defence and diplomacy. History shows that decentralisation in border regions often dilutes the chain of command between civil and security institutions—a risk India cannot afford on its Himalayan ramparts.

Strategic geography, Strategic restraint

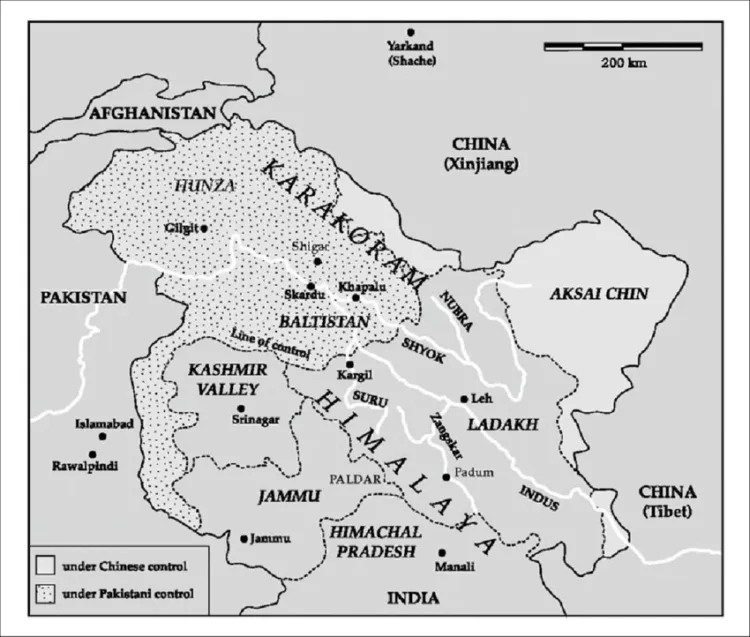

Ladakh is not an ordinary district clamouring for empowerment. It is India’s northern shield— wedged between Pakistan-occupied Karakoram and China’s militarised Aksai Chin. The Galwan clash of 2020, which took the lives of twenty Indian soldiers, remains a reminder that Ladakh’s terrain is not just about identity; it is about sovereignty.

Experts cited by The Tribune and Eurasia Review emphasise that direct central control ensures rapid coordination between army, intelligence and administration. Introducing an elected state government would mean slower file movement, conflicting political pressures and the possibility of populist posturing on national-security issues.

China’s own governance model underscores the point. Its so-called “autonomous regions”— Tibet and Xinjiang—remain tightly supervised by Beijing, because even a hint of local defiance is seen as a national-security threat. India as Bharat, though democratic, cannot ignore that logic entirely. As some analyst feel “Strategic cohesion sometimes demands administrative centralisation.”

Economic and demographic realities

Ladakh’s population barely crosses 300,000—smaller than many Indian districts. Its rugged topography, scant agriculture and dependence on central funds make statehood economically hollow. The revenue generation potential of Ladakh covers less than 10 per cent of its administrative expenditure. A state apparatus—legislature, secretariat, departments, police—would rely almost completely on central government grants, defeating the purpose of “self-reliance.”

Moreover, the Sixth Schedule was drafted for pre-Independence tribal accords in the Northeast. Extending it to Ladakh would require a constitutional amendment and could spark a domino effect, with other regions demanding identical privileges.

Existing safeguards within the UT framework

The argument that Ladakhis have “no voice” under Union control is also misplaced. Two Autonomous Hill Development Councils—Leh and Kargil—already handle planning, land use, tourism and local welfare. Their powers can be enhanced without rewriting the Constitution. Recent policy steps—85 per cent job reservation for locals, domicile protection and mandatory local consultation for land acquisition—show that empowerment need not mean statehood.

Empowering the Councils with greater fiscal autonomy and audit accountability would give citizens both participation and protection. The Centre can also consider direct Lok Sabha representation for each district and periodic consultative forums with the Home Ministry to institutionalise dialogue—reforms that preserve unity while deepening democracy.

The sixth schedule: A misfit for the mountains

The Sixth Schedule was conceived to safeguard the distinctive tribal customs of the Northeast through district and regional councils with legislative powers over land and resources. Ladakh’s demography—split between Buddhist Leh and Shia-Muslim Kargil—is vastly different. Imposing a tribal-centric framework here could entrench identity divisions and generate administrative overlap between existing Hill Councils and new Sixth-Schedule bodies.

It is important to understand that this would not only require constitutional redesign but also complicate coordination with the armed forces and ministries managing border infrastructure. Duplication and jurisdictional confusion could paralyse decision-making— precisely when swift, unified responses are vital along the Line of Actual Control.

Leh and Kargil often articulate their demands through separate religious and regional lenses. Granting statehood could convert this cultural duality into political polarisation. Under the present UT system, the Lieutenant Governor—answerable to Parliament—acts as a neutral arbiter ensuring continuity in administration and preventing factional capture of state machinery.

Lessons from China

China’s management of Tibet and Xinjiang is often criticised for its authoritarianism, but one cannot miss the underlying strategy: absolute policy uniformity in frontier zones. While India’s democratic ethos mandates dialogue and due process, it must not translate into strategic hesitation. Thus, while empathy for local grievances is essential, granting statehood or Sixth-Schedule status would fragment the command chain that underpins border management, disaster response, and infrastructure development.

Dialogue and devolution must operate within a clear national framework—not outside it.

Prudence over populism

The Centre’s restraint—ordering judicial inquiries, reopening communication channels and continuing talks—reflects democratic maturity, not suppression. But as policy experts caution, giving in to emotional appeals for “full autonomy” could embolden similar movements in other strategically sensitive regions like Arunachal Pradesh or the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. India’s unity rests on the twin pillars of inclusiveness and integrity. Empowerment must not translate into fragmentation.

A balanced roadmap forward

- Strengthen the Leh and Kargil Hill Councils: Grant enhanced financial powers, subject to central audit, ensuring transparency and faster project execution.

- Create a Permanent Ladakh Advisory Council under the Home Ministry to institutionalise local consultation without devolving sovereignty.

- Expand livelihood and infrastructure projects—renewable energy, cold-chain logistics, sustainable tourism—to generate employment within the UT framework.

- Safeguard cultural heritage through local boards and eco-zoning laws, not through parallel legislatures.

- Maintain unified command for security and foreign-policy matters under central ministries.

Such calibrated decentralisation gives Ladakhis ownership in governance while retaining the coherence India needs to guard its frontiers.

Strength lies in unity

The cry for statehood emerges from genuine aspirations, but national interest demands strategic foresight over sentiment. Ladakh is not just another administrative unit; it is India’s sentry in the clouds, the first line of defence against two nuclear-armed neighbours.

Statehood or Sixth-Schedule status, however well-intentioned, could fracture that shield with layers of bureaucracy and politicised autonomy. The wiser course lies in empowered councils, transparent governance and sustained dialogue. Ladakh’s true security lies in integration, not disintegration.

Comments