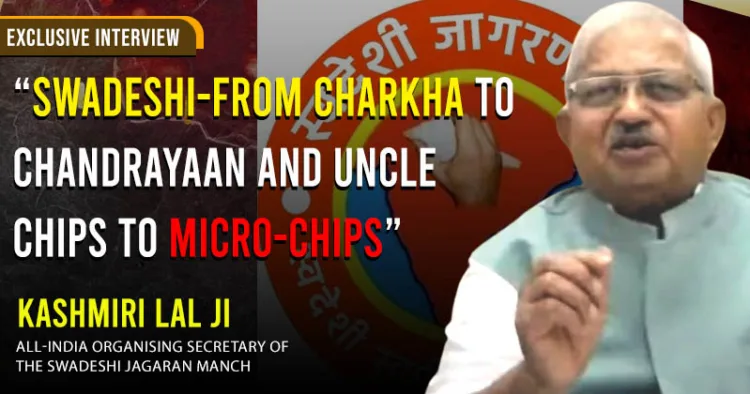

This is an excerpt from the online interview of Kashmiri Lal ji, the All-India Organising Secretary of the Swadeshi Jagaran Manch, by the Director of Bharat Niti Pratishthan (India Policy Foundation) Dr Kuldeep Ratnoo on “The Crisis of Globalisation and the Rise of Swadeshi.” Kashmiri Lal ji spoke on Bharat’s evolving Swadeshi movement, economic and technological self-reliance, challenges from globalisation, and measures to empower local businesses and secure national sovereignty

How do you view the current situation and the renewed discourse on Swadeshi?

Since the United States began imposing tariffs — particularly during trade tensions with China — the global economy has faced major upheaval. Unpredictable “tariff wars” left nations wondering about the future. Amidst this uncertainty, citizens and governments have realised the importance of self-reliance and economic independence.

The Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM) began its movement in 1991, but the nature of issues has changed dramatically. From Gandhi ji’s charkha to Chandrayaan, the journey of Swadeshi reflects remarkable evolution.

Warfare has also changed. Earlier, spies gathered intelligence; today, digital tools and 5G networks can reveal data to adversaries. Modern battles target systems, identities, and data, not just bodies and buildings. Hence, developing Swadeshi defence systems and technologies has become essential. The battles of the future will be fought with algorithms, making technological self-reliance more urgent than ever.

Although Bharat is a global IT leader, much of our talent works for foreign corporations. It is time to build our own IT houses and digital autonomy to face future challenges. While the essence of Swadeshi remains the same, its meaning continues to evolve with

changing times.

The Swadeshi movement historically resisted colonial exploitation and later pressures from globalisation. Today, a new phase of Swadeshi has emerged. Is it still a form of resistance, or has its nature changed?

The first organised Swadeshi movement arose in 1905 against the British partition of Bengal, defining Swadeshi as resistance to a dominating power. In 1991, with the WTO and the Dunkel Draft, the SJM campaigned against forced globalisation, again defending national interests.

Across all phases, the struggle has been against hegemonic forces seeking control — first the British Empire, then post-World War II economic domination through institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and mechanisms such as patents and TRIPS.

The key distinction today is that the government, public, and SJM are aligned, pursuing self-reliance together. While global players have changed — the US or China — the challenge remains the same: economic coercion, such as dumping or tariffs, that Bharat must guard against.

In essence, the three phases — 1905, 1991, and today — share a common thread: defending Bharat’s sovereignty and self-reliance against powerful global forces, adapting to changing times while continuing the same struggle.

With the movement evolving from chips to microchips and Bharat now economically stronger, does Trump’s tariff shock make the current Swadeshi push seem short-term?

Since 2014, the government has systematically promoted Bharat’s civilisational strengths. In 2015, National Handloom Day revived the memory of the 1905 Swadeshi movement, while Bharat secured global recognition for International Yoga Day — asserting indigenous knowledge on the world stage. During COVID, initiatives like “Vocal for Local” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat” ensured Bharat’s self-reliance, including the production of indigenous vaccines when external supplies were withheld.

“Swadeshi extends beyond goods to language, attire, culture, lifestyle, medicine, and even celebrations. Our values, behaviour, and worldview must reflect indigenous identity, sustaining the nation’s selfhood in both material and moral domains”

The emphasis shifted from “Make in India” to “Made by Indians,” highlighting Bharatiya labour and craftsmanship. Even defence has seen a transformation: imports of 2014–15 have been overtaken by exports in 2023–24, with targets set for 2030.

This demonstrates that the current Swadeshi push is a carefully planned, proactive strategy, not a

knee-jerk reaction.

With many Bharatiya-looking companies having significant foreign investment, should Swadeshi be defined only by market products, or should it encompass self-reliance and economic sovereignty?

Both aspects matter. As Thengadi ji noted, ownership and control often change, blurring definitions. While some companies frequently shifted hands in the past, today ownership is more stable, and in some cases, foreign brands are becoming Bharatiya-owned — for example, Tata’s acquisition of Jaguar and Land Rover. Three guiding principles can define Swadeshi: the owner should be Bharatiya; a majority of shares should be held by Bharatiyas; and headquarters and operational control should be in Bharat so profits, royalties, and intellectual property remain here. Bright packaging or Bharatiya-sounding names alone do not make a product Swadeshi.

Swadeshi extends beyond goods to language, attire, culture, lifestyle, medicine, and even celebrations. Our values, behaviour, and worldview must reflect indigenous identity, sustaining the nation’s selfhood in both material and moral domains.

With ownership patterns constantly changing, should we study and research on our own, or is there a platform tracking these shifts, especially since many people don’t read newspapers?

This confusion is precisely why the SJM exists. If everyone already knew, awareness work wouldn’t be needed — no pamphlets, website, or campaigns.

It is the duty of informed karyakartas to educate people and shape opinions. Responsibilities should be divided — tracking ownership changes, identifying foreign products or services that may harm interests, and spreading awareness. While SJM undertakes this work, broader participation will amplify its impact.

If products are assembled in Bharat using imported components, with Bharatiya workers contributing labour, should they be considered Swadeshi?

Dattopant Thengadi ji and Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya ji explained that we should ideally buy locally made goods out of choice, not just necessity — the present Prime Minister calls this “Vocal for Local.” First preference should be for products made within one’s region; if unavailable, support Bharatiya-owned all-Bharat brands (“Swadeshi by need”). Only if something is unavailable in Bharat may foreign products be used, and this compulsion should reduce over time. Deendayal ji emphasised gradual progress: foreign goods should become Indianised, and Indian goods modernised. For products like FMCG, aim for 100 per cent Swadeshi first. For imported components, at least add value through assembly and eventually develop indigenous technology.

With Bharat’s growing dependence on foreign tech platforms, how feasible is achieving technological Swadeshi, and are there examples of it already happening?

While dependence on imported goods has decreased, reliance on foreign tech services like Google, WhatsApp, Netflix, Amazon, and Flipkart remains high. These platforms not only earn huge revenues from Bharat but also store our national data. Initially used out of necessity, it’s now time to take initiative. Sridhar Vembu ji’s Zoho Corporation exemplifies Bharatiya technological self-reliance. Recently, the Railways and Education Ministry shifted many systems from Google and WhatsApp to Zoho’s “Arattai” platform. In just one year, Zoho earned over Rs 2,500 crore, largely from abroad, while all data remains in Bharat. Sridhar ji, from a small Tamil Nadu village, returned to build this global company domestically. IIT Madras offers another example. NSA Ajit Doval ji praised their indigenous 5G solution, developed in just two years under Prof Kamakoti with students and private partners, compared to China’s 14–16 years. This technology has been successfully used in defence operations.

Thus, technological Swadeshi is no longer a distant dream — it’s happening now, with innovators like Sridhar Vembu extending it to civilian applications as well.

With digital marketing and e-commerce threatening small traders’ livelihoods, what is the Swadeshi Jagran Manch doing to address this?

Recently in Nagpur, the SJM convened 45 major business institutions and unions to discuss this growing challenge. Two main approaches emerged:

1. Regulating Large Companies: Some big companies exploit deep pockets through unethical practices. Reporting mechanisms and vigilant societal oversight are crucial to ensure government action and prevent misuse.

2. Empowering Small Traders: Small businesses can compete if provided technical assistance. During COVID, over 1,000 Bharatiya companies delivered online using minimal resources, demonstrating that local traders can thrive with proper support. Government platforms and cooperative structures, like Amul, show how collective action strengthens small producers against global competition.

The SJM identifies five key focus areas to advance Swadeshi:

- Shopkeepers and Street Vendors: Bharat has around 3 crore people in these categories. Educating them on the benefits of indigenous products helps protect livelihoods.

- Students and Educational Institutions: Initiatives like Swavalambi Bharat Abhiyan engage students and teachers in entrepreneurship, making schools and colleges hubs for Swadeshi awareness.

- Caste and Community Leaders: Local influencers help spread Swadeshi principles.

- Religious Institutions: Priests and religious leaders historically played key roles in public education and continue to be vital partners.

- Social Media and Local Media: High-quality content—plays, skits, demonstrations—effectively communicates Swadeshi values to all generations.

While SJM, and RSS have different timeframes—next election, 25 years, or centuries ahead—their goals align towards promoting Swadeshi.

The vision is long-term: preparing Bharat for 2047, the 100th year of Independence. Collective effort, practical initiatives, and engagement across age groups and sectors are essential. Just as historical figures used strategy to uphold dharma, Bharat today must act strategically to empower small traders, strengthen indigenous businesses, and advance the nation’s vision globally.

Comments