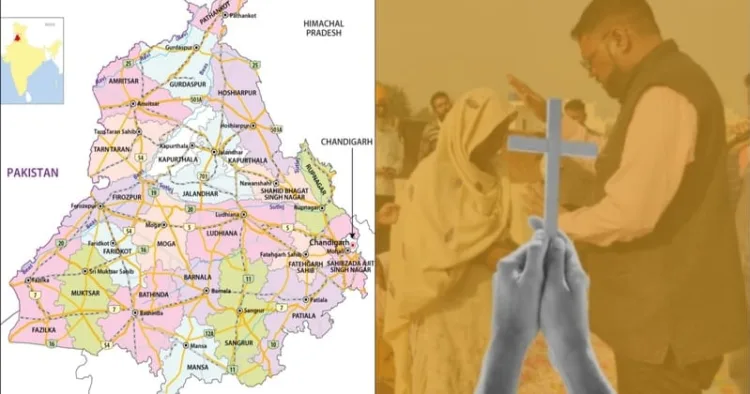

Punjab is once again confronting uncomfortable questions about its social unity, as recent events in Jalandhar reveal cracks in what has long been considered a robust, diverse, and tolerant fabric. Slogans once meant to inspire faith or solidarity are now turning into triggers for confrontation. Protests that begin as expressions of belief are quickly spiralling into communal flashpoints. And under the surface of public disorder lies a deeper, more quiet transformation that many say is reshaping the state’s cultural identity: the growing wave of religious conversions to Christianity. Taken together, these developments cannot be dismissed as spontaneous or isolated, they appear to be part of a broader and more deliberate effort to unsettle Punjab’s equilibrium.

The recent row in Jalandhar surrounding slogan-chanting began as a protest reportedly linked to the “I Love Mohammad” campaign, which originated in Uttar Pradesh but found echoes in Punjab. In what should have remained a peaceful demonstration, it turned problematic when a Hindu youth, allegedly in a personal response, shouted “Jai Shri Ram” near the protest site. What followed was not just verbal confrontation but alleged assault, threats, and police intervention. FIRs were registered for both hurt sentiments and physical violence. The issue could have ended there, as a minor clash of sentiment and misunderstanding. But it didn’t. Instead, it sparked debate on social media, drew lines between communities, and resurrected suspicions that have long been dormant in Punjab’s mixed-religious neighbourhoods.

Not long after, more incendiary signs began appearing, this time quite literally. Pro-Khalistan graffiti was sprayed across the walls of schools and public buildings in and around Jalandhar. In several cases, the messages were accompanied by references to banned foreign-based outfits like Sikhs for Justice. Arrests followed. Investigations were launched. But again, the issue was not just the graffiti itself, it was the larger sentiment it appeared to channel. Punjab has paid dearly in the past for the consequences of identity-based radicalism. So, when such messages reappear, even sporadically, they do more than deface property; they reopen wounds.

It is in this backdrop that the question of religious conversions resurfaces, now louder than ever. In cities and villages across Punjab, there are growing claims that large-scale conversions—primarily of economically weaker sections, especially Dalits—are taking place, often under the influence of external religious groups or through inducements. While data remains contested and official figures are hard to come by, community leaders, researchers, and local organizations report a sharp uptick in conversions to Christianity. A recent study cited in media reports claims over three lakh people have converted in less than two years, with Jalandhar reportedly topping the list of districts.

For many observers, this shift cannot be explained away as mere spiritual realignment. The conversions, they argue, are less about religious belief and more about social escape—a way out of caste-based discrimination, poverty, and invisibility. Yet the concern deepens when these conversions are facilitated not through personal reflection but through systemic inducements: promises of better education, free medical treatment, social status, even financial benefits. In hundreds of villages, self-styled pastors are reported to hold healing ceremonies, offer “miracle” solutions, and present Christianity as a gateway to dignity that the caste system has long denied. For the converts, it may indeed be an act of hope. But for the larger society, especially those who see their cultural and religious space shrinking, it is an act fraught with alarm.

The sense of demographic transformation—and perceived erasure—has understandably triggered a backlash. Sikh religious institutions have voiced strong objections. Some Hindu groups see it as a systematic attempt to disrupt communal balance. In both cases, the anxiety stems not just from changing numbers, but from what those changes represent: a cultural shift, a political realignment, and perhaps most critically, a weakening of old bonds between communities that have shared the same soil for generations. At the heart of it is the fear that these transformations are not organic, but engineered.

It would be naive to pretend these anxieties are baseless. Equally, it would be dangerous to overreact in a way that stokes violence or marginalises genuine expressions of faith. But what cannot be denied is the growing sense that Punjab is being pushed—subtly, steadily—toward division. The frequent appearance of provocative slogans, the increasing incidents of communal sloganeering in public spaces, and the sharp rise in religious conversion activity all appear to serve one purpose: to break the social consensus that has held this state together.

The method is not new. Across history, when a region is targeted for destabilisation, it is rarely done by brute force alone. It begins with doubt—about neighbours, about identity, about belonging. It begins with slogans shouted in crowded places or painted on school walls at night. It begins with whisper campaigns about who’s converting whom, and for what reason. Over time, such strategies weaken the social trust that communities depend on to function peacefully. And when that trust is lost, it is far harder to rebuild than it was to destroy.

What makes Punjab vulnerable to such destabilisation is its very diversity. The state is a complex patchwork of faiths and castes, of farmers and labourers, of urban centres and deeply traditional villages. It is this complexity that made Punjab resilient in the past—but it is also this complexity that can be exploited today. The actors may vary—radical religious outfits, foreign-funded NGOs, political opportunists, or ideologically motivated groups—but the outcome is the same: disruption, mistrust, and fragmentation.

The state government must respond, but so must society. Law enforcement should act swiftly, yes, but with neutrality and fairness. Arrests must be based on evidence, not sentiment. At the same time, conversions should be scrutinised—not to deny anyone their freedom of faith, but to ensure that freedom is not being manipulated. There is a line between religious propagation and social engineering, and in many parts of Punjab, that line is becoming dangerously blurred.

There is a time to argue about faith, politics, and identity. And there is a time to protect the fragile peace that allows such arguments to take place without bloodshed. Today, Punjab stands at a crossroads. If the state and its people fail to see the pattern in these repeated provocations, they risk sleepwalking into deeper unrest. What is at stake is not merely religious sentiment, but the very idea of Punjab as a shared space, a collective culture.

For now, the slogans may fade, the protests may end, the graffiti may be painted over. But unless Punjab confronts the deeper forces driving these patterns—unless it stops treating each incident in isolation and begins to see the full picture—the damage to its social fabric may soon become irreversible. A society that does not recognise when it is being divided will eventually lose the ability to stand united.

Comments