In the search for investigating life at its smallest scales, accuracy matters. For decades, researchers worldwide have employed a revolutionary tool called optical tweezers, a technology that uses light beams to trap and manipulate tiny particles. This technology was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2018, it is a common component of labs that allows scientists to study forces on individual molecules and cells.

Scientists at the Raman Research Institute (RRI), Bengaluru, with support from the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, have developed this technology. They have designed a next-generation dual-trap optical tweezers system that resolves key limitations in traditional models. Through making the device more affordable, precise and adaptable, their work may unlock neuroscience, drug development, nanoscience and other secrets.

The promise and problem of Optical tweezers

Optical tweezers achieve this by concentrating laser light onto a microscopic particle, effectively “holding” it in place. By directing these beams, researchers are able to push the particles around or detect minute forces on them. The instrument has been applied in all fields of biology, bioengineering, nanotechnology and materials sciences, where experiments often require manipulating structures only a few microns in scale.

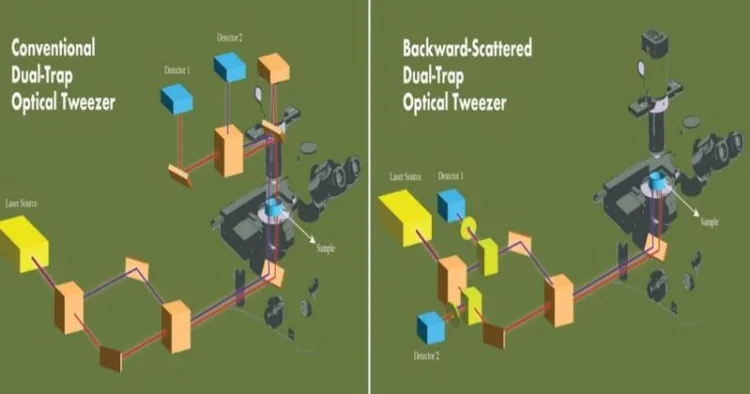

A strong configuration is the dual-trap arrangement, with two beams driving independent particles simultaneously. Researchers are able to examine interactions between trapped bodies, like protein nanomachines or biopolymer filaments, with this setup. This conventional dual-trap tweezers are accompanied by serious limitations.

Most configurations monitor the light transmitted through the trapped particles, but this method introduces three ongoing issues. First, the two traps usually interfere with their signals in a process called “cross-talk.” Engineers have attempted to counter this by employing distinct lasers or more advanced optics, but that just makes the apparatus more complicated and costly. Second, the detection systems within these designs interfere with other imaging devices, so it is more difficult to integrate tweezers with methods like fluorescence or phase contrast microscopy. Third, upon movement of traps, the detection system must be repositioned. This contributes to downtime and diminishes accuracy in dynamic experiments.

Solution from RRI

To address these issues, researchers at RRI created an optical trapping setup with a new detection method. Rather than taking the light that passes through particles, their device uses the light scattered in the backward direction by the trapped particles. This simple-appearing modification eliminates interference completely. Each detector simply observes light returning from its own trap, and thus the two signals stay independent even as the traps are brought close together.

“The unique optical trapping scheme utilizes laser light scattered back by the sample for detecting trapped particle position. This technique pushes past some of the long-standing constraints of dual-trap configurations and removes signal interference and the single module design integrates effortlessly with standard microscopy frameworks,” said Md Arsalan Ashraf, PhD Scholar at RRI.

This breakthrough allows the detectors to stay calibrated even when the traps are shifted. Scientists no longer must interrupt experiments to realign the apparatus, resulting in more efficient and stable studies. The arrangement is also fully compatible with other imaging approaches without requiring any redesign of the microscope.

Features that redefine precision

The new dual-trap apparatus offers a number of remarkable improvements over conventional models:

• No Cross-Talk: The two traps signals are entirely independent, removing one of the largest hurdles to accuracy.

• Stable Measurements: The system is stable even with temperature variations or over long-time measurements.

• Free Trap Movement: Traps can be moved away without sacrificing detection precision, allowing for dynamic experiments.

• Compact Design: The modular design can be directly installed on current microscopes without changing their structure.

• Compatibility: There is interference-free use of standard imaging methods and the system is very versatile.

“This new single module trapping and detection design makes high-precision force measurement studies of single molecules, probing of soft materials including biological samples, and micromanipulation of biological samples like cells much more convenient and cost-effective,” stated Pramod A. Pullarkat, lead principal investigator and faculty member at RRI.

Why this matters in India

For scientists, the possibility of measuring forces at the molecular level has the potential to reveal new information about how biological systems function. Being able to understand how proteins produce force, how DNA strands respond to tension or how cells adapt to mechanical stress could lead to huge leaps in medicine and biotechnology.

The new design of the RRI system is not only meant to enhance scientific precision but also to reduce costs and increase accessibility. By streamlining the design while eradicating recurrent shortcomings, the researchers have come up with a device that can be embraced by labs in India and even globally. This may help speed up discoveries in such core areas as neuroscience, drug discovery, and nanoscience.

Intellectual property and future impact

The RRI innovation has intellectual property potential. By solving the age-old issue of signal interference in a minimal but effective manner, the design is singularly for patent protection. Its beauty is that it offers a critical solution without introducing unnecessary complexity, rendering it more dependable, less expensive and more versatile than its predecessors.

Its potential impact could be significant. In the field of biology, it has the potential to reveal how motor proteins transport cargo within cells. In medicine, it will assist in creating treatments by enabling researchers to experiment with how pharmaceuticals influence molecular interactions. In the nanoscience field, it has the potential to assist engineers in designing new materials by examining how structures at the nanoscale react with force.

Scientific advancement frequently relies on effective changes in experiment design. The RRI team is redesigning dual-trap optical tweezers, which seems like a technical adjustment, also it sets enormous possibilities in the motion. By eliminating interference, reducing alignment and providing compatibility with traditional microscopes, the new system makes the equipment much more convenient and accurate.

As India consolidates its research culture, innovations such as this place the nation firmly in the forefront of pushing forward global science. From learning about the fundamentals of life to treating disease, the capacity to trap and handle particles through light may continue to revolutionise the way we learn about the microscopic universe.

The researchers of RRI believe that this new design is not merely an instrumentation improvement; it is a doorway to discoveries that may redefine biology, medicine, and nanoscience for decades to come.

Comments