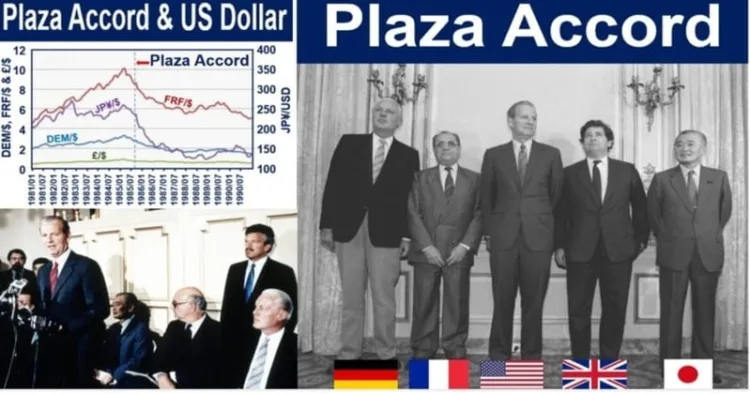

At the Plaza Hotel in New York, representatives of the then world’s five major economies gathered together. These five included the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany (then West Germany), and Japan. They came together to decide upon a new strategy, which came to be known by the hotel’s name itself – The Plaza Accord. The Accord had not only a profound impact on the economies of these five nations but also on the rest of the world.

For the first time in history, central banks of leading economies directly intervened in the currency markets to influence exchange rates. The key decision taken was that the United States would devalue the dollar. The backdrop was this: between 1980 and 1985, the dollar had appreciated by nearly 46 per cent. While the US economy was growing at around 3 per cent, the currencies of other countries remained weaker, giving them an export advantage. Yet, these four economies were struggling — their growth rates were negative, averaging around -0.7 per cent. Meanwhile, the US dollar kept strengthening, and the dollar index (which measures the dollar’s value against a basket of currencies) soared to 160.

A major driver behind the move was America’s growing current account deficit, while the other four economies, especially Japan, were running trade surpluses. Japan, being an export-driven economy, particularly benefited from a depreciated yen. The dollars it earned through exports were reinvested heavily in the US. Treasuries, which only strengthened the dollar further. Under President Ronald Reagan, the dollar reached its strongest level ever, driven by America’s domestic economic policies.

At the Plaza Hotel, it was agreed that the US would devalue the dollar, while the other countries would allow their currencies to appreciate. Additionally, the UK and France committed to reducing government spending and channelling more capital to the private sector. Germany and Japan agreed to implement tax cuts. The core aim of the Plaza Accord was to reduce America’s trade deficit, particularly with Japan and Germany, and restore trade balance.

The devaluation of the dollar did not happen overnight but gradually. The US dollar fell, while the currencies of the other four appreciated, especially the Japanese yen and the German mark. The intended outcome was partially achieved: America’s trade deficit with Germany declined and eventually turned into a surplus after a few years. However, with Japan, the trade deficit hardly improved, though the Japanese economy faced significant repercussions.

From the 1970s through the 1980s, Japan had rapidly expanded its industrial base, becoming a major exporter to the US. A weaker yen had worked in its favour, allowing Japanese goods to flood American markets at low prices. US multinationals like Caterpillar and IBM raised concerns in Congress that Japan’s undervalued currency was giving it an unfair edge, hurting American industries. This pressure was instrumental in pushing for the Plaza Accord.

Once the dollar was devalued, US exports became cheaper abroad, boosting demand for American goods. By 1991, the US had managed to shift its current account balance into surplus, proving the Plaza Accord’s long-term effectiveness for America.

Between 1985 and 1988, major currencies appreciated by about 40 per cent against the dollar, but the yen rose the most, by nearly 50 per cent. In 1985, the yen traded at 240 per dollar; by 1988, it had strengthened to 120 per dollar. For Japan’s export-oriented economy, this was a severe blow. Exporters suffered, while domestic financial markets overheated. Japan experienced an asset bubble: stock market and real estate prices soared. The Nikkei index hit record highs by 1989, only to crash soon after. The collapse triggered decades of stagnation, a period often referred to as the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s. Growth slowed sharply compared to the double-digit expansion Japan had enjoyed in the 1970s and 80s.

Even today, 40 years later, Japan has not regained the growth momentum of its earlier years. While Japan’s economy continued to remain the world’s second-largest until 2009, its overall growth has been modest. In 1985, Japan’s GDP stood at $1.43 trillion compared to America’s $4.23 trillion. Today, the US economy is nearly $30 trillion, about 7.5 times larger, while Japan’s is around $4 trillion, barely quadruple its 1985 size. Clearly, the Plaza Accord left a lasting impact on Japan’s trajectory.

As the dollar kept depreciating, the 1987 Louvre Accord was signed to stabilise exchange rates, ensuring that the dollar would not fall below a certain level and other currencies would fluctuate within limits. Even so, Japan was left with long-lasting effects. Its ultra-low interest rate policy eventually transformed Japan into a global creditor, supplying cheap liquidity worldwide.

The yen plays a unique role in global liquidity. Being undervalued compared to the dollar, it boosts Japanese exports and sustains massive foreign exchange reserves (around $1.3 trillion today). With the yen trading at roughly 147 per dollar, these reserves are significantly amplified in dollar terms.

Ultra-low interest rates in Japan created the famous yen carry trade: global investors borrowed cheaply in yen and invested in higher-yielding assets abroad, earning large profits. This capital flowed into equity, real estate, commodity, and money markets worldwide, inflating asset prices and providing global liquidity. In many ways, the Bank of Japan became a de facto central bank to the world.

However, if Japan now raises interest rates and allows the yen to appreciate, it will have sweeping global consequences. Not only the US but most world economies would be affected. Indeed, Japan has recently started to raise rates cautiously after years of zero or even negative interest rates.

Comparing then and now: in 1985, the US devalued the dollar to reduce its trade deficit. Today, President Trump faces similar pressures. He has imposed tariffs and threatened more, but he, too, knows tariffs alone cannot solve trade deficits, currency adjustment is key. With the dollar once again extremely strong, if the US opts to devalue, it could ease its current economic challenges, though this would significantly impact countries with high trade exposure to the US, such as China and Japan. India, however, stands in a unique position. Since India is not heavily dependent on exports and has a vast domestic market, a weaker dollar would not harm it much. In fact, cheaper imports would benefit India.

Ultimately, structural changes are necessary to pull economies out of crisis, and exchange rate realignment is one such structural measure. The US devalued the dollar only once, in 1985, under the Plaza Accord. Today, with the dollar again at historically strong levels and trade imbalances mounting, the world may be approaching a similar turning point. History appears ready to repeat itself, and the moment for another dollar devaluation may already have arrived.

Comments