National Nutrition Week highlights the importance of aligning tradition with science. A Sattvik diet, rich in millets, pulses, greens and fermented foods, not only nurtures gut microbiome diversity but also strengthens India’s fight against malnutrition and lifestyle diseases

National Nutrition week (1-7 September), initiated by the Food and Nutrition Board in 1982, is the annual event where India needs to turn culture of public health. Article 47 of the Constitution documents that it is “duty of the state to raise the level of nutrition and the standard of living and to improve public health”.

According to the 2024 Global Nutrition Report, India continues to face alarming nutrition challenges. Stunting among children under five stands at 34.7 per cent, while the Asia regional average is 21.8 per cent, while wasting is reported at 17.3 per cent as compared to Asia’s 8.9 per cent, reflecting little progress. Anaemia among women of age between 15–49 yrs remain critically high at 53 per cent.

The NFHS-5 (2019–21) further highlights that 35.5 per cent of children under five are stunted and 19.3% are wasted. Globally, experts stress the first 1,000 days from conception to two years after birth as a crucial window to combat malnutrition, while India’s nutrition programmes have mostly focused post-birth. Research shows that half of growth failure by age two originates in the womb due to poor maternal nutrition before and during pregnancy, underscoring the importance of pre-conception care.

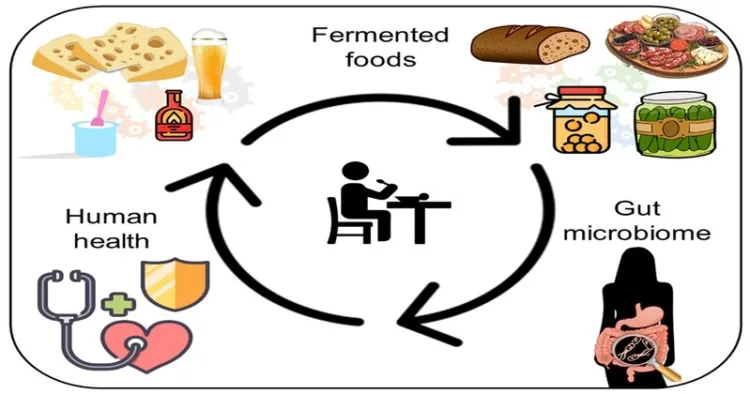

The Eat Right Movement promotes predominantly plant-based balanced diets, already central to Indian food culture, as a sustainable way to provide essential nutrients, antioxidants and dietary fibre for optimal health while preventing overnutrition. Here’s how a Sattvik plate rooted in tradition lines up with hard microbiome science and what policymakers and cooks can do this week to make it real.

The Kitchen as India’s First Laboratory

For many Indians, stepping into a traditional kitchen is like entering a living laboratory of nutrition science. The shelves are lined with jars of grains, pulses and spices, each carrying centuries of accumulated wisdom. Take millets for example. Beyond its cultural revival, it has now become an important part in nutrition science for their impact on gut health. According to a 2021 study published in Frontiers in Nutrition, the dietary fibre’s in millets not only improve glycaemic index but also act as prebiotics, enriching beneficial bacteria in the colon and supporting microbial fermentation. The fermented foods like buttermilk or pickles has been a long part of Indian meals and are being re-examined by microbiologists worldwide for their probiotic potential in restoring gut diversity. What once seemed like grandmother’s “home remedies” are increasingly being validated in labs.

Why The Microbiome Cares About a Sattvik Plate

The human gut is an ecosystem: trillions of microbes metabolize what we eat into small molecules that interact with our immune system and metabolism. A central class of those molecules are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate and butyrate, produced when microbes ferment diverse dietary fibres. SCFAs strengthen the gut barrier, tame inflammation and help regulate glucose and lipid metabolism. Interventions that increase plant-food diversity and whole-food fibre intake tend to raise SCFA production and microbial diversity in controlled studies, giving a mechanistic anchor to the idea that a fibre-rich Sattvik plate can be health-promoting.

Fermented Foods: Culture On the Plate and in the Gut

Across India, everyday fermented foods like curd, idli/dosa batter, dosa’s fermented batter, regional pickles and buttermilk are not culinary curiosities but live microbial introductions. A well-controlled Stanford intervention showed that adding fermented foods to the diet for ten weeks increased gut microbiome diversity and reduced inflammatory markers in participants, compared with a high-fiber intervention alone. That’s critical because higher diversity frequently though not always correlates with better metabolic and immune outcomes. Practically, adding modest servings of homemade or well-prepared fermented items to school and community meals is low-cost and evidence-backed.

Millets, Resistant Starch and Local Grains: Feeding Beneficial Bugs

Millets like finger millet (ragi), pearl millet (bajra), sorghum (jowar) are rich in different fibres and resistant starches that escape digestion in the small intestine and are fermented in the colon. Emerging reviews find that millet fibres help enrich beneficial microbial taxa and may improve glycaemic responses and markers tied to diabetes risk. In an Indian context, substituting a portion of refined rice or wheat with millets can therefore do double duty: revive traditional crops (nutrition and climate resilience) and provide substrates that nurture a healthier microbiome.

Ritual Fasting and Intermittent Fasting: Overlapping Mechanisms

Traditional monthly fasts like Masik Shivratri, Ekadashi and others often produce patterns similar to what clinical nutritionists call intermittent fasting (IF). Recent umbrella reviews of randomized trials show if can reduce waist circumference, fat mass and some cardiometabolic risk markers in adults with overweight or obesity, though benefits vary by regimen and population. The ritual framework matters: fasts embedded in household practice are socially supported and often accompanied by lighter, more plant-forward meals when the fast is broken, conditions that may amplify metabolic and microbiome benefits. That said, fasting isn’t for everyone: children, pregnant women and those with specific health conditions should not adopt prolonged fasts without medical supervision.

From Lab to Plate: What National Nutrition Week Can Do

National Nutrition Week is best used as a laboratory for culturally aligned pilots. Here are concrete, low-friction actions that fold science into tradition:

Sattvik Plate Pilots in Mid-Day Meals and Anganwadi’s: Replace one weekly menu item with a millet-based khichdi, a cooked green, a pulse dish and a small serving of curd. Measure acceptability and simple biomarkers where feasible (weight, haemoglobin). Evidence from microbiome and diet studies suggests the combination of whole grains + pulses + fermented food is more impactful than isolated supplements.

Community cooks training: Fermentation increases microbial resilience in the gut but requires hygiene and standard practices. Short training modules on how to ferment idli batter safely, set curds and prepare low-salt home pickles are inexpensive and scalable; Stanford’s trial design shows dose and quality matter.

Public messaging against ultra-processed fiber claims: The market now teems with “fibre-fortified” snacks that promise gut health but lack the complex matrix of whole foods that feed diverse microbes. Nutrition Week should highlight whole-food fibre and caution against over-reliance on fortified processed products. Journalistic and clinical reviews have raised similar cautions.

A Realistic, Evidence Based Sattvik Plate

For the realistic based diet, one should try these in their kitchen and can witness the changes from pre pregnancy, Anganwadi programmes and individual health.

- Base: millet or brown rice (resistant starch + fibre)

- Protein/fibre: moong or mixed dal (sprouted if possible)

- Greens: local seasonal greens, lightly cooked with turmeric

- Fermented element: curd/ buttermilk/ idli/dosa (small serving)

- Fruit/nuts: for micronutrients and polyphenols

This combination mirrors interventions shown to increase beneficial metabolites and microbial diversity better than single-ingredient fixes.

Microbiome science is young. Not every high-fibre food acts the same in every person; responses vary by baseline microbiome, genetics and prior diet. We must avoid breathless claims that “sattvik food cures X.” National Nutrition Week to conduct pilot study, collect real-world data and pair cultural messaging with clinical caution, especially for vulnerable groups.

The power of a Sattvik approach is not purely nostalgia. It is a pragmatic alignment of seasonal foods, simple cooking, fermentation and occasional fasting, practices that scientific literature increasingly recognizes as beneficial for the gut and by extension for population health. National Nutrition Week can convert that alignment into policy pilots such as menus in schools, training for cooks and public communication that insists on whole foods over packaged promises. Doing so would be both modern and an example of tradition and evidence converging at the family table.

Comments