Sanskrit, a language of unparalleled mathematical and psychological perfection, stands as one of the true wonders of the world. Its profound influence and unique attributes have garnered global recognition throughout history, yet ironically, it still struggles for rightful acknowledgement in its homeland, India. This paradox demands introspection and corrective action.

Historical Acclaim and Global Recognition

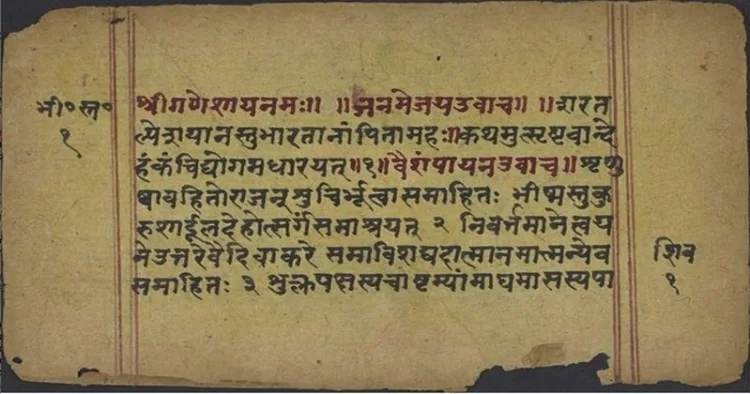

Maharishi Panini, a revered Sanskrit grammarian, logician, and philologist of ancient India, famously declared, “he who knows my grammar knows God.” He further emphasiSed the language’s depth, stating, “he who would track language to its lair must indeed end in omnisciente.” The veracity of this declaration is supported by the fact that no other language aligns as remarkably with modern computational linguistics, owing to its systematic and unambiguous grammatical structure.

Sanskrit’s global recognition is not a recent phenomenon. During the East India Company’s rule in India, Sir William Jones, a brilliant 18th-century scholar, arrived in 1783 as a judge of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort Williams in Bengal. He became deeply interested in Sanskrit and, within six years, mastered the language. His observations highlight its perfection: “Devanagari character, in which Sanskrit language is written, is adapted to the expression of almost every known gradation of sound, and every letter has a fixed and variable pronunciation.” He extolled Sanskrit as “more perfect than the Greek, more copious than Latin and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of the grammar, that could possibly have been produced by accident, so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them without agreeing that they have the same origin with the Sanskrit.” Having deeply studied Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic, Chinese, and his native English, Sir William Jones placed Sanskrit at the pinnacle of languages.

Another renowned admirer was Max Muller, a German philologist and orientalist, and one of the founders of Indian studies in the Western academic field. He profoundly stated, “If I was asked under what sky, the human mind has most fully developed, pondered over the greatest problems and found solutions to some of them, even those who might have studied Plato and Kant, I must point to India.” Muller translated the Rigveda and authored “A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature,” further cementing Sanskrit’s global prominence.

Today, Sanskrit is taught in universities worldwide, spanning Australia, North America, Belgium, Denmark, Britain, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, Russia, Norway, Netherlands, Switzerland, Japan, Thailand, and even China, where it is gaining popularity. This global trend serves as a vital lesson for India to develop a stronger commitment to its propagation within the country.

Cultural and Philosophical Significance

Historically and culturally, Sanskrit is established as the elder sister of Greek, Latin, and Persian, and a cousin of English, French, and Russian. Simple comparisons, such as “mother” and “father” to “मातृ पितृ” (matri, pitri), illustrate its profound influence on Indo-European languages.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, unhesitatingly declared, “If I was asked what is the greatest treasure which India possess and what is her finest heritage, I would answer unhesitatingly- it is the Sanskrit language and literature and all that it claims. This is a magnificent inheritance and so long as this endures and influences the life of our people, so long the basic genius of India will continue.”

Sanskrit is the mother of all Indo-Aryan languages and the sacred tongue in which the four Vedas were revealed. Moreover, the Puranas, Upanishads, Rishi Valmiki’s Ramayan epic, Rishi Ved Vyas’s Mahabharat epic, and the Bhagavad Gita of Lord Krishna also known as “The Song Celestial”, were all realised and handed down to mankind in lucid Sanskrit. Swami Vivekananda ji has described Bhagavad Gita as a, “bouquet of beautiful flowers picked up from the garden of Upanishads.” He saw it as a grand commentary on Vedas and a source of profound spiritual wisdom. The father of the nation, Mahatma Gandhi, daily read the Bhagavad Gita and had it marked that without studying the Bhagavad Gita, he would have gone mad for not showing courage to fight the war of freedom for India. Classical works by Kali Das, Banbhatta, and Dandi were also penned in this language. The profound teachings of Shankaracharya, Ramanuj, MadhawaCharya, and Vallabhcharya, which are intricately woven into Indian culture, would not have been possible without Sanskrit as their medium of expression.

Paramahamsa Yogananda Ji, a globally acclaimed spiritual leader and ambassador of Kriya Yoga, emphasised Sanskrit’s profound impact on the human body. He noted in his commentary on the Bhagavad Gita that “50 sounds of the Sanskrit alphabets are on the petals of the ‘Sahasrara’ (thousand-petalled lotus receiving center of cosmic energy seated in medulla oblongata). The sounds of Sanskrit alphabets effect 72,000 ‘Nadis’ (nerves) in our physical body.”

A powerful anecdote from World War II underscores the importance of cultural preservation. When the City of London was heavily bombarded, a Cambridge University professor, despite the city-wide blackout, continued his studies. When questioned by an enraged British sergeant about his lack of patriotism, the professor countered by asking why the sergeant fought the war. The sergeant replied that they fought to preserve English culture from German subjugation. The professor then explained that he, too, was contributing to that culture through his studies. This interaction highlights how deeply individuals contribute to the preservation of their cultural heritage. Similarly, for the people of India, holding the cultural heritage of this ancient land in high esteem is paramount, and learning Sanskrit is undoubtedly necessary for its protection. The stream of our heritage would undoubtedly dry up if the study of Sanskrit were discouraged.

Constitutional recognition and Educational importance

Sanskrit has already secured its rightful place as one of the recognised languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. It is of utmost significance that without learning Sanskrit, it is impossible to decipher the Indian philosophy upon which our culture and heritage are based. Furthermore, Sanskrit is considered the mother of almost all Indian constitutionally recognised languages.

The Government of India established a Sanskrit Commission in 1957. The commission’s report recorded that “Sanskrit is one of the greatest languages of the world and is classical language par excellence not only of India but of a good part of Asia as well.” It further stated that “Indian people and the Indian civilisation were born in the lap of Sanskrit and it went hand in hand with the historical development of the Indian people and gave the noblest expression of their culture which has come to us as an inheritance of priceless order for India, may for the entire world.”

The Central Government’s 1968 “Education Policy” echoed these sentiments, stating, “considering the special importance of Sanskrit to the growth of development of Indian languages and its unique contribution to the cultural unity of the country, new methods of teaching the language should be encouraged. It should be taught in such modern subjects as modern Indian philosophy.”

The Supreme Court in the nine-judge Constitutional Bench case, titled S.R. Bommai v. Union of India 1994 (3) 1, has clarified that secularism, a basic structure of the Constitution, means a secular state which is not hostile to religion but remains neutral in religious matters. It treats the devout, the agnostic, and the atheist alike, as exemplified by figures like Vivekananda and Gandhi, whose teachings embodied the essence of secularism. Therefore, promoting Sanskrit does not militate against the basic tenet of secularism.

In another significant decision on October 4, 1994, the Supreme Court in U.P. Hindi Sahitya Sammelan and others Versus Ministry of Human Resources Development and another, held that Sanskrit must be included in the syllabus of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) as an elective subject. The Court reiterated the Constitutional directive of Article 351, by emphasizing that Article clearly mandates in plain language that it shall be the duty of the Union to promote the spread of the Hindi language, to develop it so that it may serve as a medium of expression for all the elements of the composite culture of India and to secure its enrichment by assimilating without interfering with its genius, the forms, style and expressions used in Hindustani and in other languages of India specified in the Eighth Schedule, and by drawing, wherever necessary or desirable, for its vocabulary, primarily on Sanskrit, and secondarily on other languages. Not only that, whatever has been held by the Supreme Court, otherwise also, from a bare reading of the language of the above stated Article, it becomes as clear as day that the Constituent Assembly of India, while framing the Constitution had also recognised primary and paramount importance of Sanskrit language while upholding the secondary importance of other languages. By way of abundant care and caution, at the end, the Supreme Court had emphasised that this does not imply the imposition of Hindi or any language on any community or individual. The court has consistently advocated for linguistic secularism, meaning no language should be imposed on anyone, and that all languages, including regional languages, should be respected.

The above observations would apply with equal force to Hindi, which has been termed the beauteous daughter of Sanskrit. The court has further held that the learning of Sanskrit was a must to decipher the Indian philosophy, on which our culture and heritage is based. The matter in hand was concluded by saying that in view of the importance of Sanskrit for nurturing our cultural heritage, because of which even official educational policy has highlighted the need of the study of Sanskrit, making of Sanskrit alone as an elective subject, while not conceding this status to Arabic and/or Persian which would not, in any way, militate against the basic tenet of secularism. Finally, in the above-stated case, a direction was issued to include Sanskrit as an elective subject in the syllabus.

Revival in J&K: A lost legacy restored

Historically, the Kashmir valley was a prominent hub of Sanskrit scholarship. Kashmir Shaivism, a non-dualistic school of Hindu Philosophy expressed in Sanskrit, originated there thousands of years ago. Sharda Peeth University, a temple of Goddess Saraswati, was one of the subcontinent’s premier learning centres, attracting students even from foreign countries. From Sharda Peeth, Sanatana Dharma was revitalised after Adi Shankaracharya’s debates with Buddhist monks, particularly after Buddhism had overshadowed Sanatana Dharma from King Ashoka’s time (273 BCE) to King Lalitaditya’s period (764 AD). The Buddhist monks were also erudite scholars of the Sanskrit language who represented their views in the debates with Shankaracharya from their religious books.

Even after the establishment of an Islamic state in Kashmir in the 14th century, Sanskrit continued as the official language for about 150 years. This pattern of governance changed under Sultan Sikandar Shah Mir’s rule (1389-1413), known as “idol breaker,” who switched to Persian as the official language and simultaneously destroyed hundreds of temples and thousands of Sanskrit scriptures. He persecuted Hindus, forcibly converting some, and defiled the Shardha Goddess temple.

However, this period of tyranny ended with the noble Sultan Zayn al-Abidin’s rule (1420-1470 AD), who is known as “Baadshah” for his humane qualities. He abolished Jaziya (tax) on Kashmiri Hindus, banned cow slaughter, extended liberal patronage to Sanskrit, repaired places of worship, and facilitated the return of Hindus who had migrated for safety.

Regrettably, after India’s independence, the Kashmir Valley became barren for the retention, teaching, and learning of Sanskrit. The eruption of militancy and terrorism in 1989/1990 further exacerbated this, forcing the aboriginal Hindu population to leave their ancestral homes, initiating an era of erosion for Sanatana Dharma, its cultural institutions and consequential erosion of the Sanskrit language.

Now, with the bifurcation of the State into two Union Territories, the J&K UT government has largely re-established the rule of law and maintained communal harmony. This change has created an environment where Hindu cultural institutions are protected, and public harm to the age-old culture is met with suitable penal retribution with utmost alacrity.

The founder of the State of Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Gulab Singh, descends from the clan of Shri Ramji. Thousands of years ago, his (Ram’s) descendants migrated from Ayodhya to different parts of the country, primarily in Rajasthan. History records that an ancestor of the rulers of the Jammu region, namely, Agni Barn, had migrated from Rajasthan nine hundred years before the setting in of the “Kal Yug” and established his rule over this sacred and spiritual landscape. Maharaja Gulab Singh, after founding the state of J&K on the foundations of the short-lived Sikh rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab, had his first preference to revive, reinforce, and spread more vigorously the Vedic culture by preferably constructing various temples in Jammu and Kashmir devoted to his family deity Shri Ram. The Raghunath Temple in the heart of Jammu city is one of such shining examples. After his death in 1857; his surviving illustrious son Maharaja Ranbir Singh ascended the throne. Maharaja Ranbir Singh forwarded the family legacy more effectively and vigorously. The incomplete Raghunath Temple complex, which was started in 1830 by his father (Maharaja Gulab Singh), was completed by him in 1860. He established within the temple complex “Shri Raghunath Sanskrit Mahavidyalaya” and a comprehensive library of manuscripts within the temple premises (herein to be referred to as Mahavidyalaya). It is renowned for its vast and invaluable collection of manuscripts, estimated to be around 6000 to 8000, with many being extremely rare. This collection encompasses a wide spectrum of theological and scholarly subjects. It remains a vibrant centre of learning, a repository of ancient wisdom and a significant contributor to the ongoing efforts of preserving India’s rich linguistic and intellectual heritage. In other words, the whole complex stands as a testament to the rich intellectual and spiritual heritage of the Dogra Dynasty, particularly the vision of Maharaja Ranbir Singh. Maharaja Ranbir Singh, being a devout patron of scholarism and a keen promoter of Sanskrit learning, recognised the importance of preserving ancient texts. He even dispatched teams of pandits across India to acquire as many rare manuscripts as possible. This ambitious undertaking aimed to make Jammu a prominent centre of Sanskrit learning and consequently earn the “Moniker Kashi of the North”. While evaluating the whole Centre in a straitjacket formula, it transpires that it was Maharaja Gulab Singh who initially, during his lifetime, had conceived the noble idea to make provision of necessary infrastructure for the learning and propagation of Sanskrit.

In the premises of Raghunath Temple, Jammu, free boarding and lodging facilities were established to provide the education of Sanskrit upto degree (Shastri) level. The students not only from the state of J&K but also from the adjoining province of undivided Punjab, which then included the present state of Himachal, used to stay in the premises and receive free education. In the same manner; steps were also taken for the preservation and spread of Vedic culture in Kashmir Valley. Vedic scholars were getting employment as Pujaris of large number of temples built inside the different complexes. Maharaja Rabir’s son, Maharaja Pratap Singh, who was more religious-minded, also followed suit. To the same extent, the last ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh, till the abolition of Dogra rule in 1947, continued to look after the family interest in the usual customary manner to provide all the facilities to the lovers of Indian Vedic culture and to the students of Mahavidyalaya, all the facilities extended to them. When his authority came to an end following the political developments of 1948, Maharaja Hari Singh was effectively sidelined from the affairs of the State and subsequently compelled to exile from J&K for good. He settled in Bombay (now Mumbai) and breathed his last there. The sacred and spiritual onerous moral duty was carried forward by his sole illustrious son, namely Dr. Karan Singh, who himself happens to be a great scholar and philologist. He is erudite in English, Sanskrit, Hindi, Dogri and Urdu languages etc. During his long tenure as a titular head of Jammu and Kashmir State and then Member of Parliament (Indian Nation al Congress) from 1967 onwards over a span of multiple decades as well as Cabinet Minister holding important portfolios, his global contributions to Vedic philosophy are:- Delivered lectures across Europe, United States of America and Asia on Vedanta, Upanishads and interfaith harmony, promoting Indian spiritual legacy on global platforms like: (1) UNESCO (2) World Parliament of Religions (3) Global Peace Conferences. Scholar and Author: Authored books and essays interpreting Vedic wisdom in the modern context, including “One man’s world”, “Towards a new India”, “Hymn to Shiva and other poems”. The last classic spiritual treatise, “Shiva Lord of Cosmic” was authored in 2022.

Leadership in Indian Philosophical Institutions

Chairman, Indian Council for cultural relations, promoted Sanskrit texts and Indian philosophy abroad.

President, Aurovilla foundation – helped spread Sri Aurobindo’s integral philosophy, rooted in the Vedas, etc.

This customary family prominence ceased to exist within the premises of Sanskrit Mahavidyalaya when the “National Sanskrit Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan” formally took it over and renamed it “Shri Ranbir Kendriya Sanskrit Vidhyapeetha”. In 2007, the campus was relocated from its old rented premises near Raghunath Temple to a dedicated new campus at Kot Bhalwal, Jammu, built on about 10.5 acres (85 Kanals) allotted by the Jammu and Kashmir Government. The new infrastructure includes the main academic building, library, hostels and staff quarters. With the passage of the Central Sanskrit University Act, 2020, this institution was officially recognised as “Shri Ranbir campus” under the Sanskrit University from 2020 onwards. In this university, courses are taught right from Shastri (B.A. in Sanskrit), Post-graduate courses, and Doctoral programs in different streams of learning. Objectives of the campus are: (i) preserve and promote Sanskrit as a vital part of Indian heritage, (ii) provide traditional Sanskrit education with modern relevance, and (iii) promote research in Indian philosophy, literature, grammar, and science.

The enduring wonder of Sanskrit

To truly appreciate why Sanskrit is considered one of the wonders of the world, consider the extraordinary feat of the 17th-century poet Venkatadhavri from Kanchipuram. He compiled a unique work called “Raghavyaadviyam” (राघवयादवीयम् ग्रंथ), comprising 30 couplets. What makes this work astounding is that if read from left to right (anulom), it narrates the Ram Katha, and if the same shlokas are read in reverse order (vilom), they narrate the Krishan Katha, effectively creating 60 narratives from 30 shlokas.

For instance, the first shloka illustrates this remarkable linguistic duality:

Anulom (Ram Katha): I bow to Bhagwan Shri Ram, in whose heart Sita resides, who went to Lanka via the Sahyadri hills to slay Ravana for his wife Sita, and who returned to Ayodhya after completing his exile.

Vilom (Krishna Katha): I bow to Bhagwan Shri Krishna, revered by Rukmini and the Gopis, who always resides with Maa Lakshmi, and whose splendor surpasses the beauty of all jewels.

This unparalleled linguistic artistry is a testament to Sanskrit’s profound structure and richness. It is imperative that “We the people of India” uphold the cultural heritage of this ancient land. The learning of Sanskrit is undeniably necessary for the protection of this heritage, for the stream of our heritage would dry up if we were to discourage its study. It is time to elevate Sanskrit within our educational ethos, recognizing its vital role in understanding Indian philosophy, culture, and heritage, and seeing it not as a challenge to secularism but as a cornerstone of our national identity

Comments