The recent order enabling the return of 110 bighas of premium land in Mandi, Himachal Pradesh to the heirs of Meer Baksh and others has stirred not just local politics but a far deeper constitutional unease. Valued at over Rs 1100 crore and located near Nerchowk Medical College, this is not an ordinary property dispute. It sits squarely at the intersection of judicial reach, statutory exclusivity, and the architecture of India’s federal system.

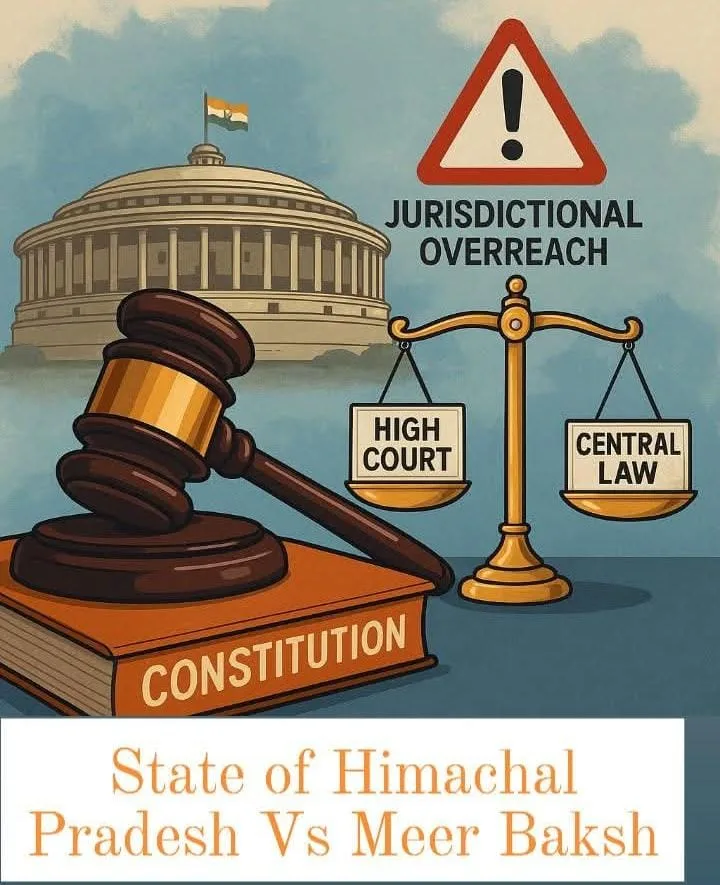

At first glance, the matter appears to be one of restitution to private claimants. But a closer reading reveals a more consequential question: Can a High Court, in its writ jurisdiction, pronounce upon the evacuee status of property that stands vested in the Central Government under a Parliamentary enactment, thereby stepping into a field reserved for a central statutory authority?

On 19 July 2023, a two-judge Bench comprising Justices Abhay S. Oka and Sanjay Karol upheld the Himachal High Court’s orders, dismissing the State’s appeal in State of Himachal Pradesh & Ors. vs. Meer Baksh & Ors.. Crucially, the Court observed that the State had categorically admitted that Sultan Mohammad -the predecessor-in-title never left India, making him ineligible to be classified as an ‘evacuee’ under Section 2(f) of the Administration of Evacuee Property Act, 1950. The apex court affirmed that a property cannot be declared evacuee property when the owner never left India, thereby reinforcing the exclusive jurisdiction of the Custodian under the statute and reprimanding the State’s decision to proceed with the appeal.

Yet, even with such clear Supreme Court direction, the High Court had entered terrain reserved for Central authority-potentially setting a precedent of judicial overreach despite explicit statutory prohibition.

The Administration of Evacuee Property Act, 1950 is not a minor procedural code; it is a central legislation born of Partition, designed to create a uniform mechanism across the country. It vests exclusive jurisdiction in the Custodian to determine whether a property is evacuee property (Sections 7 and 46). This is no accident of drafting, Parliament consciously insulated such determinations from fragmented, ad-hoc adjudication to ensure certainty, uniformity, and finality.

When a High Court assumes that role, even indirectly or on the basis of counsel’s concession, it risks more than just procedural irregularity. It potentially:

Displaces the statutory forum specifically created for such determinations.

Erodes the central legislative scheme, allowing State-level variation in matters Parliament intended to be uniform.

Generates jurisdictional conflict, where the Custodian’s decision and the court’s ruling may point in opposite directions.

Such overreach is not merely a matter of institutional etiquette; it strikes at the very marrow of the federal compact. The Constitution’s distribution of powers- legislative, executive, and judicial is not ornamental. It is a safeguard against chaos, forum-shopping, and the dismantling of hard-won legal frameworks.

The precedent danger here is acute. If courts begin to treat evacuee property determinations as open to writ adjudication, statutory exclusivity will be reduced to a paper formality. Concessions by counsel, often made for tactical or settlement purposes may inadvertently become the basis for jurisdictional trespass.

The remedy is neither radical nor disruptive

A reaffirmation that where Parliament has vested powers in a specialised authority, those powers cannot be short-circuited by writ orders on merits.

A recognition that concessions cannot substitute for statutory determinations.

Judicial restraint in matters where legislative intent is manifestly to centralise and standardise decision-making.

The Mandi, Himachal Pradesh case is thus not only about who gets 110 bighas of fertile land. It is a litmus test for whether our higher judiciary will observe the carefully drawn jurisdictional boundaries that keep India’s federal structure intact.

If the Constitution is to remain more than an aspirational text, the lines Parliament has drawn must not be casually crossed-even with the noblest of intentions.

Comments