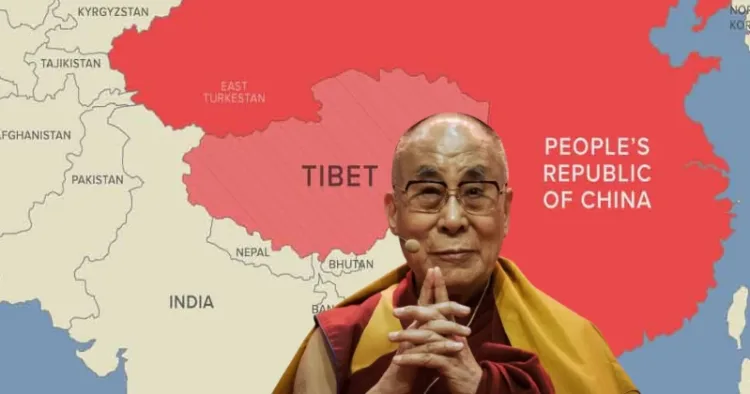

The Dalai Lama’s succession affairs have sparked simmering tensions between India and China. While China has assertively challenged the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation, India has made few symbolic moves. However, India’s Tibet policy offers limited assertiveness and strategic restraints, which seem unsuitable to current and evolving Indo-China dynamics, especially on Tibet. Therefore, New Delhi must revisit its Tibet policy and introduce some dynamic changes to prepare for and counter China’s plans if it decides to raise the stakes on Tibet and threaten India’s strategic interests.

India’s Beginning With Tibet

Tibet was a buffer state between India and China with cultural and religious ties to India through Buddhism. Tibet’s boundaries were defined under the Simla Convention in 1914, which was signed by British India, China, and Tibet. Still, China refused to comply with the convention after it annexed Tibet in 1950. After the 1950s, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, recognised Tibet as part of China in the 1954 Panchsheel Agreement, prioritising Indo-China relations. However, the dynamics between India and China began to shift in 1959 when India offered asylum to the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees, establishing the Tibetan government-in-exile in Himachal Pradesh’s Dharamshala. After establishing Tibet as part of China, India continued to acknowledge it in 1988 during Rajiv Gandhi’s visit and in 2003 during Vajpayee’s visit to China. India’s neglect of the Tibetan issue aimed to reduce friction in India-China relations, which were strained by war and territorial disputes. However, this full restraint approach gradually shifted to strategic restraint in 2010, when India ceased to explicitly endorse the One China policy due to China’s disregard for India’s territorial claims.

Nevertheless, it still maintained a non-recognition policy towards Tibet and its exile government in Dharamshala. In 2014, India adopted a more assertive stance to counter China’s influence and hegemonic moves along the Line of Actual Control. This began when PM Modi invited the CTA’s head, Lobsang Sangay, to his swearing-in. In 2021, Modi publicly wished the Dalai Lama on his birthday, as the situation at the LAC had become tense following the Galwan clash in 2020. This symbolic assertiveness was further intensified last year when India announced plans to rename sites in Tibet in retaliation for China renaming places in Arunachal Pradesh. In the same year, India also hosted a US delegation supporting the Tibet Policy Act, symbolically asserting its position on Tibet without endorsing the US’s Tibet policy.

Need For Dynamic Shift In Tibet Policy

India must move beyond symbolic assertiveness to effectively counter China’s influence in Tibet and prepare for potential symbolic aggression by China if it chooses to escalate the Tibet issue with India. The current policy is merely an irritant with little deterrent value against China. These symbolic moves do not help India leverage its position and instead complicate its relationship with Tibetans, who see India’s support as driven by geopolitical motives rather than genuine backing for Tibetan autonomy. The Dalai Lama himself noted in his autobiography that US support was more about anti-communism than Tibetan autonomy, which may reflect India’s limited support for Tibetans. Beyond deterrence and cultural ties, India also faces strategic challenges if it continues to ignore the real threat that may emerge shortly, especially considering the Dalai Lama’s succession. Tibet acts as a buffer zone, with India sharing a 3,500 km border primarily with Sikkim, Ladakh, and Arunachal Pradesh. China has greater deterrence value and disruptive capabilities against India if it decides to escalate tensions over Tibet and deters India from interfering in the Dalai Lama’s succession plans. In such a scenario, New Delhi seems to be in a difficult position. Another scenario is if China succeeds in appointing the Dalai Lama’s successor. It would be a significant geopolitical setback to India’s influence in South Asia and its ties with Tibetans. Both scenarios will impact and question India’s growing deterrence capabilities against China. The present policy doesn’t offer an effective strategy against China on Tibet, and current simmering tensions, especially China’s effective role in supporting Pakistan during the India-Pakistan clash in May this year. India must realise that China has already been intensifying its proxy and deterrence strategies against India, and such evolving dynamics present a much-needed opportunity for India to reshape its approach towards Tibet and incorporate sustainable and realistic elements to enhance its deterrence value and leverage the situation against China at the global level.

Reshaping Its Tibet Strategy Against China: Moving Towards Strategic Assertiveness

India needs to incorporate elements of sustainable and strategic disruption against China through both overt and covert means. Sustainable disparity will hinder China’s ability to exert and expand its influence in the Tibetan Autonomous Region while also facing pressure on the global stage. First, the covert means—India’s intelligence agency has already engaged in a limited proxy operation against China by training Tibetans to trigger insurgency under a covert program run by the US CIA, codenamed Operation Circus, from 1957 to 1969. Throughout this long program, India’s Intelligence Bureau, even before the formation of R&AW, facilitated logistics for trained Tibetan fighters and helped them smuggle themselves out to the US for guerrilla warfare training. Later, the Special Frontier Force (SFF) was formed, comprising Tibetan fighters under India’s command, which helped in tapping Chinese telephone lines for the CIA, which yielded minimal success. Cut to 2020, during the Galwan Clash, the SFF force was now disbanded and known as Establishment 22(a special forces command under R&AW), which played a key role in conducting Intelligence operations against the Chinese.

Taking the operational advantage further, India’s intelligence agency, R&AW, can conduct limited psychological operations to disrupt China’s political influence, which can deter China from increasing its political activities in Tibet and heighten the stakes of succession affairs shortly. As the CIA’s declassified document in 2012 suggests, India sent some monks to Lhasa to encourage anti-China sentiments and even a plan of assassination of Wu Jinghua, a Chinese politician who was the party secretary of Tibet. CIA also ran a limited psychological operation in Tibet codenamed Operation Bailey aimed at disseminating pro-Tibetian messages via radio and raising awareness about Chinese oppression and human rights abuses against Tibetans. These operations have influenced and contributed to the Tibetan Uprising in 1959.

The 2008 Tibetan Unrest is a key example illustrating the potential of psychological operations against China. In April 2008, a series of demonstrations and protests erupted against Chinese persecution of Tibetans and to commemorate the 49th Tibetan uprising day. Inspired by the March 1959 protests, these events saw massive participation, leading to their spread throughout the Tibetan plateau. These protests resulted in Chinese civilians being killed and stores and buildings being destroyed. Although China brutally suppressed the movement, it did create a noticeable impact not just regionally but also globally, as protests against China occurred in Europe, India, and other parts of the world, with the US’s State Department issuing a warning to US citizens attending the Beijing Olympics. Notably, the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics also experienced minimal impact.

Similarly, India can establish covert mechanisms to disrupt China’s influence in Tibet, which has increased significantly in recent years. This will further help in undermining China’s ability to create a political roadmap for Tibet, especially regarding its succession plans. Although it offers tactical deterrence, it has the potential to leave a lasting impact on Tibetan minds.

The overt mechanism, on the other hand, should gradually strengthen the Indo-US partnership on the Tibet issue by mobilising support for the US’s Tibet Act. Disruption in Tibet will elevate US policy efforts by providing an opportunity to internationalise the Tibet issue and exert global pressure on China over human rights concerns. US diplomatic and political cooperation with India can help diplomatically encircle China at the international level, thereby further boosting Indo-US relations and enhancing their joint policy efforts in countering China. India can change its Tibetan refugee policy of 2014 to make it more open and inclusive for Tibetans. In this overt mechanism, India must carefully manoeuvre, as it needs to avoid becoming too close to the US, which could disrupt the power balance and open the door to an India-China confrontation.

This overt-covert arrangement in India’s shifting Tibetan policy faces few challenges. First, India’s response should not be too strong or aggressive, as it could provoke China to cause disturbances on the eastern front. Second, China’s increasing policing presence and influence in Tibet have led Tibetan elites to believe they are part of China. Therefore, a complete makeover isn’t as easy as it seems, but if it is planned strategically with the right operational priorities and diplomatic engagement, it is achievable. India should focus on a minimal operational scale with high impact to achieve strategic assertiveness. India can no longer afford to sit on the fence with a limited response, as upcoming Indo-China dynamics on Tibet are most likely to be tense and contested.

Comments