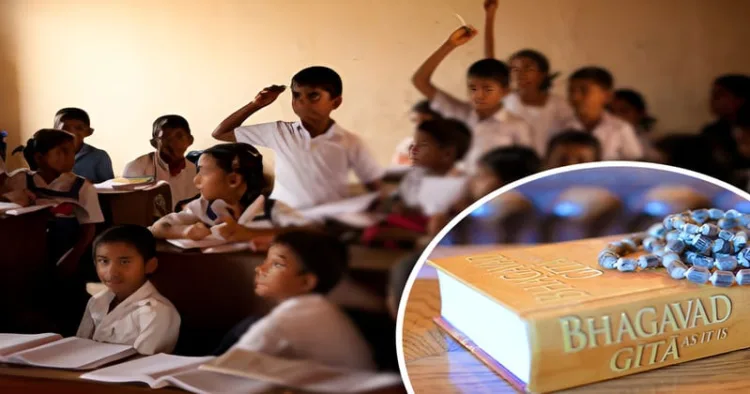

In a significant move seen as part of a broader effort to correct decades of ideological imbalance in Indian education, Uttarakhand’s Education Minister Dhan Singh Rawat announced on July 16 that the state has urged NCERT to include the Bhagavad Gita and Ramayana in the academic syllabus of 17,000 government schools.

“In a recent meeting with the Chief Minister, the Education Department directed NCERT to incorporate the Bhagavad Gita and Ramayana into the school syllabus,” Rawat told ANI. He added that until the updated curriculum is introduced, students would recite selected verses from these sacred texts during daily prayers.

This push reflects a growing national trend to reclaim India’s civilisational narrative in the classroom — a story often sidelined or reduced in past decades due to ideological slants that favoured Eurocentric and Marxist historiographies. The left-leaning academic establishment has long been accused of portraying India’s cultural and spiritual traditions as regressive or irrelevant, while downplaying indigenous achievements in science, philosophy, and governance.

Now, under the NEP 2020, a conscious effort is underway to reshape educational content — bringing history closer to heritage, and promoting a balanced understanding of India’s cultural roots alongside its scientific progress.

On July 15, NCERT released a new textbook titled Veena, which is emblematic of this new direction. The book blends tradition with modernity and is designed to foster cultural pride while nurturing scientific inquiry. One chapter, Ganga ki Kahani, follows the river’s journey from Gomukh to Gangasagar, weaving together geography, spirituality, and economy. It celebrates the spiritual heritage of cities like Varanasi and Prayagraj, while also highlighting ecological and economic aspects — an approach previously uncommon in mainstream textbooks. Another chapter introduces middle schoolers to Artificial Intelligence (AI), demystifying how machines think and solve problems, promoting scientific thinking from a young age.

The book also delves into India’s space ambitions through a chapter on Gaganyaan, spotlighting ISRO’s human spaceflight mission and the humanoid robot Vyommitra, effectively linking modern innovation with national pride.

Importantly, Veena doesn’t shy away from teaching moral and civic values. Nyay Ki Kursi uses the legacy of just rulers like Raja Bhoj and Vikramaditya to teach fairness, while Haathi aur Cheenti uses animal allegory to promote road safety awareness, blending storytelling with life lessons.

Other chapters spotlight icons and places often ignored in previous syllabi, such as Paralympic gold medalist Murlikant Petkar, the Ajanta and Ellora caves, Kaziranga National Park, and traditional methods of natural dye-making.

This cultural recalibration, as seen in both the Uttarakhand initiative and the release of Veena, marks a decisive turn away from the erasure or dilution of India’s heritage in education. It signals a growing consensus that for students to truly understand modern India, they must first engage with its past, not just through colonial or ideological filters, but through its own epics, thinkers, and innovations.

The National Council of Educational Research and Training has introduced major revisions in the Class 8 History textbook, further aligning with efforts to present a more balanced and fact-based view of India’s past.

In a landmark shift, the revised edition explicitly calls Babur a “brutal invader” and redefines Akbar as “a blend of brutality and tolerance.” Aurangzeb is now described as a “temple destroyer” who ruled with severity and religious intolerance. These changes bring long-overdue clarity to the portrayal of medieval rulers, countering decades of whitewashing in history education. The chapter once titled in neutral terms now appears under the heading “Dark Ages,” reflecting the true nature of those turbulent times. Earlier versions often softened the impact of foreign invasions, forced conversions, and violence under ideological pretexts.

This move is part of NCERT’s broader initiative to remove Eurocentric and Marxist biases from textbooks.

The aim is to present Indian history with greater honesty, acknowledging both achievements and suffering without distortion.

Comments