Before diving into the complexities of declining fertility, imagine a village with 1,000 elderly residents and no youth. Would any company consider investing in such a place? Would it be feasible to plan for the next 50 years? The answer, unsurprisingly, is no. This scenario, though hypothetical, mirrors the realities faced by many countries grappling with sub-replacement fertility—a demographic trend that challenges economic growth and societal structures.

A wide discussion has once again started on the population of Bharat. It is worth noting that in 2023, India left China behind and become the most populous country. That is, India has become a country with more population than the combined population of America, Europe and Africa. While there is a section which sees population as a problem, the other section considers it as a resource for development. Let us try to know what are the scientific reasons behind the increasing population? What does the global experience say in this context?

According to the research report of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Bharat is going through a phase of demographic dividend. Twenty five per cent of India’s population is in the age group of 0-14 (years), 18 per cent between the age of 10 to 19, 26 per cent in the age group of 10 to 24, 68 per cent between the age group of 15 and 64 and seven per cent of the population is above 65 years of age. Statistics show that India’s population growth rate is on the decline yet due to the large base India’s population will grow for the next three decades to its highest level (in terms of numbers) of 165 crores, after which the phase of decline in Indian population will begin. In any case, it took 75 years for India’s population to double, while the global population took 76 years to increase from four billion to eight billion, that is, India’s population growth rate is close to the global average, which is witnessing a gradual decline.

What was the Objectives of National Population Policy 2000

- The NPP’s primary goal is to handle unmet healthcare infrastructure, people, and contraception demands.

- Additionally, it seeks to offer integrated services for primary reproductive and pediatric healthcare.

- By adopting cross-sectoral working strategies, the medium-term goal is to raise the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) to replacement levels (TFR of 2.1) by 2010.

- The long-term goal is to stabilise the population by 2045 at a level that satisfies the demands of societal development, environmental preservation, and sustainable economic growth.

- In 2022, Bharat’s total fertility rate (TFR) was 2.01 children per woman, which is just below the replacement level of 2.1

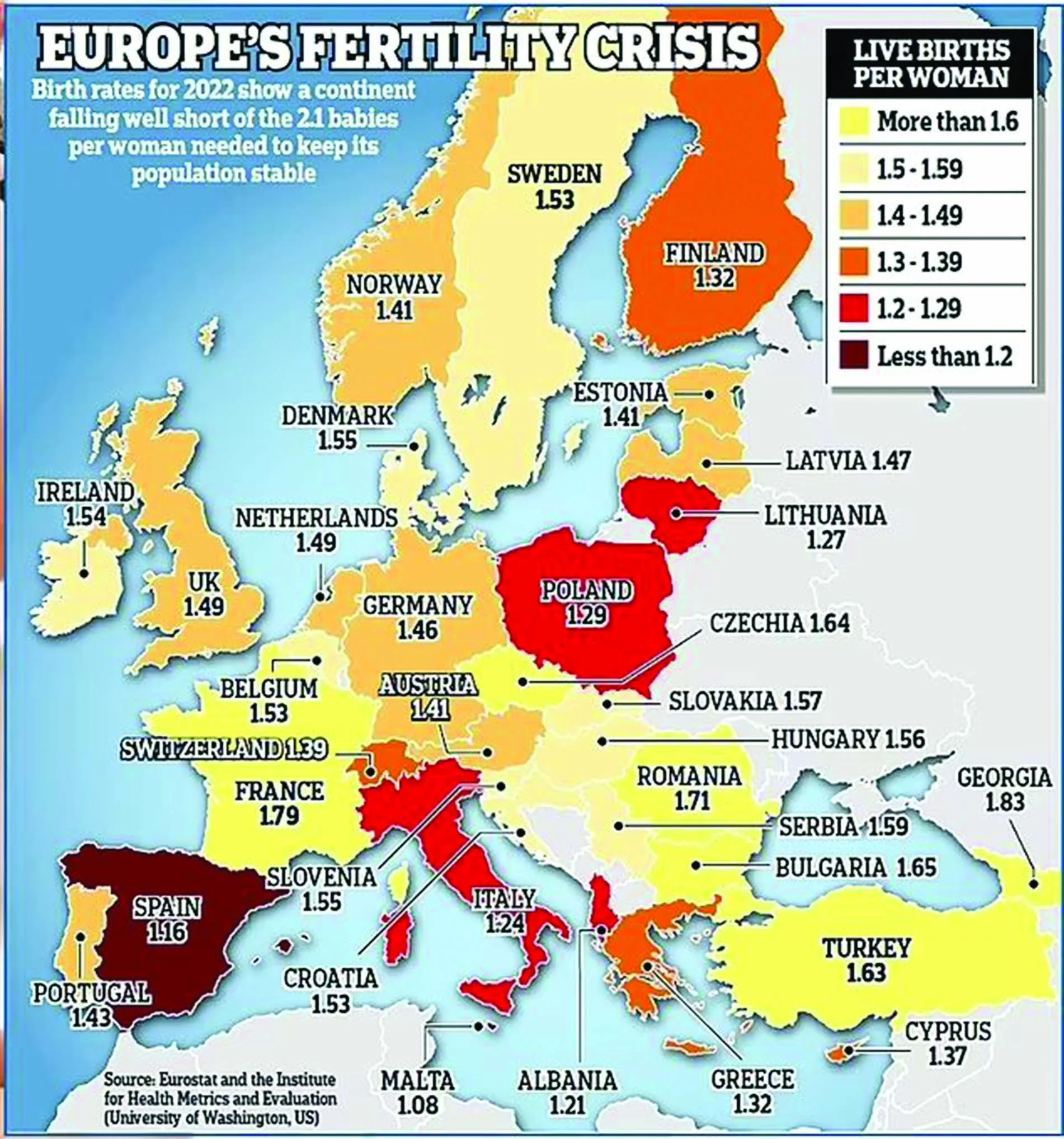

It is worth noting that India has achieved the replacement level of Total Fertility Rate (TFR) (TFR of 2.0 in 2020). From the declining level of fertility, it can be inferred that women and girls of India are increasingly able to control their reproductive choices. At the same time, a total of 31 States and Union Territories of India (69.7 per cent of the country’s population) are below the replacement rate. The pace of decline in fertility is not the same in all the States of the country. The Southern States started declining TFR much earlier than other States. The global decline in fertility rates is reshaping economies and societies, presenting both unprecedented challenges and opportunities. Total Fertility Rate (TFR), the average number of children a woman is expected to have, is critical for population stability at 2.1. Yet, 55 nations now fall below this threshold, according to UNFPA. South Korea’s record-low of TFR is 0.78 and Italy’s 1.24 exemplify the looming cris of sub-replacement fertility.

55 countries of the world have policies for increasing the TFR , because they have reached at dangerous level of 2.1, which is accepted scientific norm. Bharat is among those countries whose replacement rate is at between 1.9-2.0. Hence, we need a rational, sane discussion on a uniform population policy for all.

Shrinking workforces are at the heart of this issue. OECD projections indicate South Korea’s labour force will shrink by 35 per cent by 2050, while Japan’s will contract by 23 per cent. These declines stifle innovation, reduce tax revenues and threaten global competitiveness. Simultaneously, ageing populations are straining resources, with governments redirecting funds toward pensions and healthcare, exacerbating fiscal imbalances.

Economic activity also suffers as ageing populations shift consumption patterns, emphasising healthcare over discretionary spending. Savings depletion by the elderly further constraints investments, hampering growth. Countries like South Korea and Japan, despite pouring billions into pronatalist policies and technological interventions, struggle to reverse these trends. Meanwhile, Italy, Spain, and Germany face similar stagnation despite comprehensive childcare and parental benefits.

Managing Population

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) of 2019-2021, India’s TFR ranged from 1.4 to 3.0. Interestingly, except for the three large States – Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh, all other States have achieved below replacement fertility levels. India is demographically diverse, so declining States can maintain continuity in economic activities by managing their population by attracting migrants from other States.

One of the major reasons for the concern of Indian policymakers is the religious imbalance of population growth. Another dark side of the Indian population is that due to increasing life expectancy and other reasons, the number of elderly people is increasing rapidly. According to the India Aging Report of the United Nations Population Fund in September 2023, in the next 27 years, the number of elderly people will increase rapidly.

Transcending Borders

The economic implications of sub-replacement fertility transcend borders. Whether it’s South Korea’s shrinking workforce, Japan’s ageing population, or Europe’s policy struggles, the message is clear: adapting to demographic changes is not optional—it’s imperative. By learning from successful models and fostering global cooperation, nations can navigate these challenges and build resilient, inclusive economies. For India, the time to act is now, leveraging its demographic dividend and maintaining the population momentum.

Comments