In an intriguing exploration of cultural appropriation and misinterpretation, the story of Devi Lajja Gauri—an emblem of creation and fertility in Hindu tradition—serves as a glaring example of Western Indologists’ tendency to demonise or distort significant symbols and deities from the Vedic era.

Devi Lajja Gauri, often depicted with fertility, creation, and nurturing attributes, holds a revered place in Hindu mythology. Her iconography, rich with symbolism, underscores themes of life, abundance, and the nurturing aspects of the feminine principle. Yet, this revered deity has not escaped the tendrils of Western interpretation, which have often misconstrued her essence.

During their extensive studies of Vedic scriptures and symbols, Western Indologists frequently grappled with the challenge of contextual understanding. Their attempts to translate and interpret the myriad symbols of Hinduism often lacked the contextual depth intrinsic to these ancient texts and traditions. This gap in understanding has led to numerous misinterpretations, and perhaps none is more striking than the renaming and vilification of Devi Lajja Gauri as the “Shameless Woman.”

This transformation of Devi Lajja Gauri’s identity is not just a simple linguistic misstep; it represents a broader pattern of Western scholars imposing their cultural biases and moral frameworks onto Hindu deities. By labelling her as “shameless,” these Indologists stripped her of her sanctity. They turned her into a symbol of moral decay, far removed from her original depiction as a deity of fertility and creation.

Renaming and demonising such deities highlights a significant issue in studying ancient cultures. The Western academic lens, often clouded by colonial and patriarchal perspectives, tended to oversimplify and misrepresent complex spiritual and cultural symbols. This approach distorts historical narratives and perpetuates a skewed understanding of the rich tapestry of Hindu mythology.

Scholars and devotees argue that a more nuanced approach to studying Hindu deities is essential. Understanding the cultural, historical, and spiritual context in which these deities evolved is essential. Devi Lajja Gauri, with her profound connection to the cycles of nature and the fundamental processes of creation, deserves a respectful and accurate representation.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement within the academic community and among Hindu scholars to reclaim and reinterpret these deities in their true light. By shedding light on the original meanings and significance of figures like Devi Lajja Gauri, these efforts aim to restore the dignity and authenticity of Hindu symbols distorted over centuries.

As the dialogue between different cultural narratives continues, it becomes increasingly important to approach ancient texts and deities with an open mind and a respectful attitude, free from the biases of contemporary interpretations. Only then can we hope to honour the true essence of these timeless symbols and their place in the rich mosaic of human heritage.

In the ancient Vedic texts, Devi, revered as Lajja Gauri among her many forms, embodies the essence of the Great Mother Goddess, known by names such as Aditi, Adya Shakti, Matangi, Yallamma, and others. Within the framework of Sanatan Dharma, she stands as the most ancient and foundational deity.

According to Rig Veda, I.89.10:

अदितिरद्यौर आदितिरन्तरिक्षहं आदितिर्मता स पिता स पुत्र .

विश्वे देव आदितिः पञ्च जन आदितिर्जतं आदितिर्जनित्वम् .

Meaning:

“Aditi is the sky, Aditi is the air,

Aditi is all the gods,

Aditi is the Mother, the Father, and the Son,

Aditi is whatever shall be born.”

This verse praises Aditi, depicting her as the encompassing force within the cosmos. She embodies the sky and the air, the divine essence permeating all gods and all creation. Aditi is celebrated as the nurturing Mother, the protecting Father, and the progenitor of all that comes into existence.

Her presence in the Rig Veda underscores her pivotal role in the Vedic pantheon, symbolising fertility, creation, and the eternal cycle of birth and rebirth. Aditi’s multifaceted identity as the universal Mother Goddess reflects ancient Vedic seers’ deep spiritual and philosophical insights, highlighting her as the primordial source from which all life emerges.

This hymn not only venerates Aditi’s cosmic significance but also emphasises her omnipresence in the unfolding of existence. It captures the profound reverence and awe with which the Vedic tradition regards Aditi, affirming her as the fundamental deity in the eternal tapestry of Sanatan Dharma.

2. Aditi Uttanapada – The Devi maa of fertility and creation and the most ancient form of Lajja Gauri

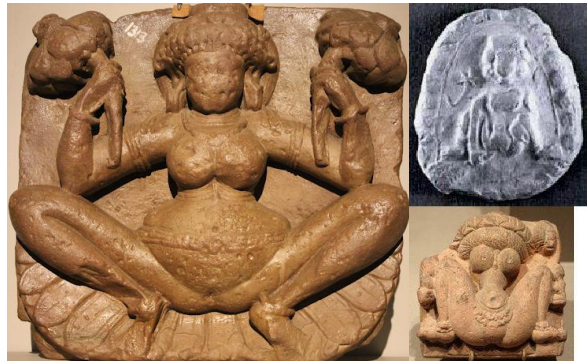

Devi Aditi, known as the primordial form of Lajja Gauri, is symbolically represented as the “birth-giving pot goddess,” a deeply potent and elemental image of fertility and creation. This iconography features human legs in the uttanapad pose, supporting a form resembling a pot and a female’s lower torso. Notably, this figure lacks an upper torso, arms, or a head, with the pot-like torso often depicted as a brimming vase, symbolising abundance and fulfilment akin to the purna kumbha.

Rig Veda, X.72.3-4, offers profound insights into Devi Aditi:

देवअं युगे प्रथमे.असतह सदाजयायत

अदास अन्वजयन्ता तदुत्तनपदस परि

भउर्जजना उत्थानपदो भुव असा अजाय

न्तादितेर्दक्षोअजायता दक्षद् वदितिः परि

Meaning: “In the first age of the gods, existence was born from nonexistence. The quarters of the sky were born from Her who crouched with legs spread. The Earth was born from Her who crouched with legs spread, and from the Earth the quarters of the sky were born.”

3. Lajja Gauri Lotus-headed without arms

The depiction of Lajja Gauri as Lotus-headed and without arms represents a unique and symbolic form within Hindu iconography, distinct from the uttanapad pot goddess imagery. In this manifestation, the torso extends to the shoulders, incorporating human-like features such as breasts and a carefully detailed abdominal area with a navel. Notably, this form lacks arms and a conventional head, with a lotus elevated to sit atop the shoulders, where a head would typically be.

The Lotus-headed Lajja Gauri is characterised by a torso that, while more human in form compared to the pot-like representation, retains mystical and symbolic elements. The lotus, a revered symbol in Hinduism connoting purity, enlightenment, and divine grace, serves as a substitute for the head. Lotus rosettes are often positioned at the sides of the shoulders, intricately integrated into the figure.

This iconography emphasises fertility and divine feminine energy, with the lotus symbolising spiritual enlightenment and transcendence. The absence of arms and a head suggests a transcendence of physical limitations, focusing instead on embodying spiritual qualities and cosmic energies.

The portrayal of Lajja Gauri in this form reflects profound metaphysical concepts within Hindu mythology, encapsulating the union of material and spiritual realms.

4. Lajja Gauri Lotus-Headed with Arms

This form depicts a deity with a lotus-shaped head, possessing a female anthropomorphic body adorned with breasts. Its two upraised arms extend from the full torso, each delicately holding a lotus bud. The legs are positioned in the uttanapad pose, symbolising purity and creation through the lotus buds held in its hands.

5. Lajja Gauri in Complete Avatara

In this complete avatar of Lajja Gauri, she appears as an anthropomorphic figure with a human head atop a natural female torso. Her arms are raised, with each hand grasping a lotus bud, similar to Form III. Her legs are positioned in a pose symbolising birth-giving.

6. Meaning of Maa Lajja Gauri’s symbols

The symbols associated with Maa Lajja Gauri carry profound meanings rooted in ancient beliefs about fortune and fertility. Artists depicted these symbols within the female form, often in a birthing posture, to convey the Goddess’s inherent power through their rich cultural significance. Three key symbols stand out:

Lotus:

In Indian art, the lotus symbolises fortune, fertility, and life cycle. It embodies future generations’ potential and signifies life’s renewal and regeneration, akin to reincarnation.

Brimming Pot:

Similar to the lotus, the brimming pot symbolises well-being, fertility, and the life-giving power of water. It also metaphorically represents the womb (Yoni). The depiction of breasts, flanking buds, and a fully bloomed lotus at the head may draw inspiration from the association with the purna kumbha.

Srivatsa:

Srivatsa is a mark of fortune depicted as a whorl of hair, a triangle, or a cruciform flower. In its early form, it featured four upwardly curved ‘limbs’. There is a symbolic connection between Lajja Gauri and Srivatsa, linking her to deities like Sri, Sri Lakshmi, and Gaja Lakshmi, all associated with well-being.

7. Appropriation of the Sanatan Symbol of creation

In an article published by the Government of Odisha titled “Lajja Gauri: The Nude Goddess or Shameless Woman – Orissan Examples,” Maa Lajja Gauri is referred to as a “shameless woman.” This prompts us to question whether we should seek instances of appropriation beyond India’s borders.

(Link: https://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2009/September/engpdf/137-138.pdf)

8. Maa Lajja Gauri’s Reverence in Buddhism

Near Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India, a statue depicting Maa Lajja Gauri beside Bhagwan Buddha highlights her revered status within Buddhism.

9. The Metaphysical Meaning

The fertility aspect of Lajja Gauri is underscored by symbolic representations such as the blooming Lotus flower, symbolising youthfulness in some depictions, or a straightforward yet intricate portrayal of an exposed vulva. Often depicted in a squatting (uttanpada) position, with legs spread as in childbirth, sometimes with the right foot positioned on a platform to facilitate openness, she is invoked for bountiful crops (vegetative fertility) and healthy offspring.

In certain representations, her head and neck are replaced by a blossoming lotus, an icon commonly used in Tantra. Similar to how the seven Chakras of human energy anatomy are depicted as blooming lotuses, she is often symbolised in her Sri Yantra form as a Yoni represented simplistically as a central triangle.

Ancient fertility goddesses frequently appear headless in iconography, placing significant emphasis on the genitals. Lajja Gauri’s bent arms are typically raised, each grasping a lotus stem positioned at head level, representing the matured lotus flower—a powerful symbol of spiritual and material advancement since Vedic times.

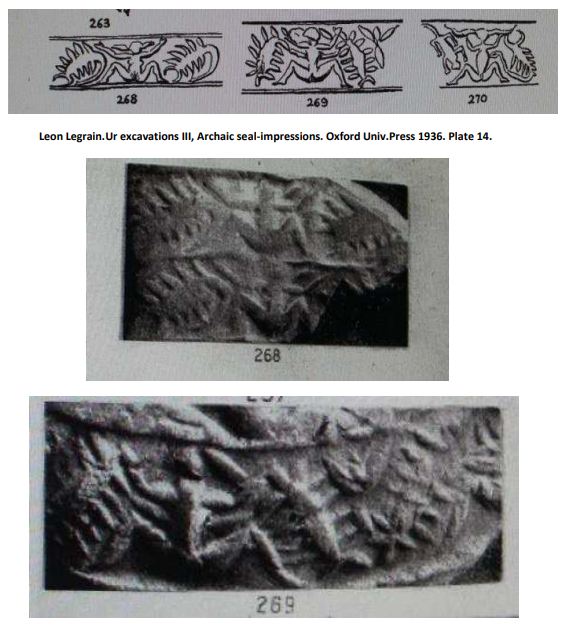

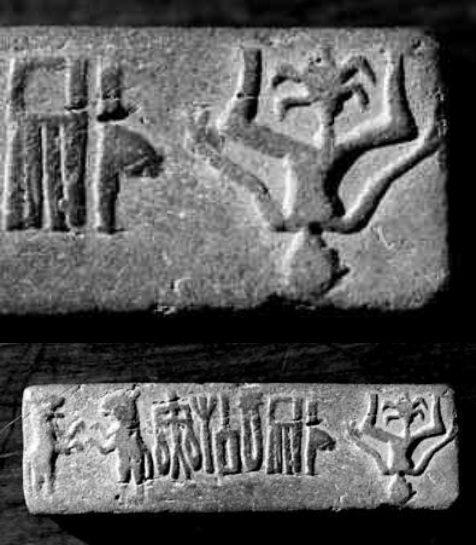

10. Lajja Gauri’s depiction of Indus Valley seals portrays her in a manner that highlights her significance in ancient iconography

11. Fertility Goddesses in Ancient Mesopotamia: Lajja Gauri Counterparts

During the rule of Ur in the Mesopotamian region from 3100 BC to 2700 BC, the Sumerians worshipped Inanna, their fertility goddess, and her avatars, including Lamashtu and Lilitu (known as Ardat-Lili to the Akkadians). These deities were associated with eroticism and fertility rituals. Lilitu, depicted simply and nude, often with legs spread to reveal her vulva, symbolised the act of procreation and birth. She was sometimes surrounded by scorpions, which held symbolic significance in Sumerian culture as representations of sexual intercourse.

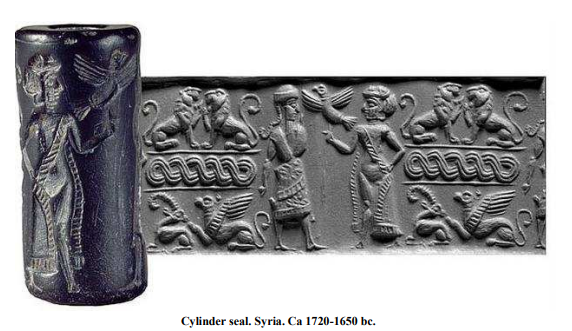

12. Fertility Goddesses Beyond Borders: Ninegala of Ancient Syria

Seals and statues depicting the fertility of Ma Ninegala from ancient Syria highlight her significance in the region’s religious and cultural heritage.

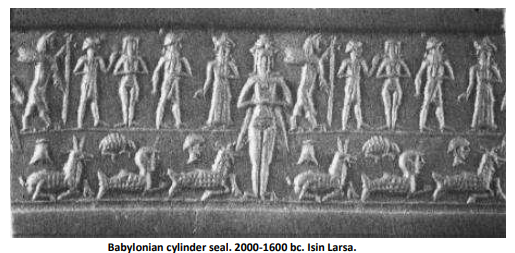

13. Counterparts of Lajja Gauri in Other Civilisations: The Ancient Sumerian Ma Ishtar

14. Counterparts of Lajja Gauri in Other Civilisations: Babylonian Seal Depicting Inana, the Fertility Goddess

15. Harappa valley seals depicting Lajja Gauri symbolism of fertility

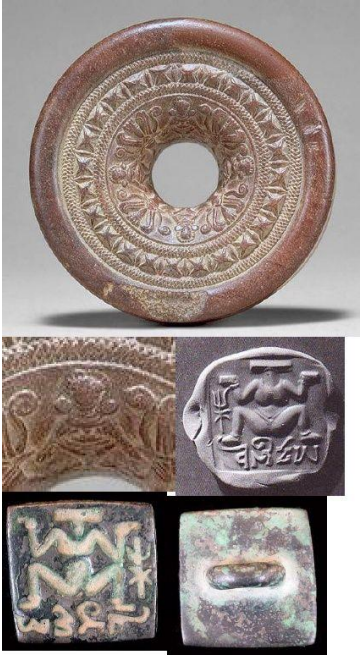

16. Lajja Gauri as depicted on the ring stone of the ancient Maurya Kingdom of India

17. Lajja Guari as depicted on the coins of ancient Saurashtra Janapada

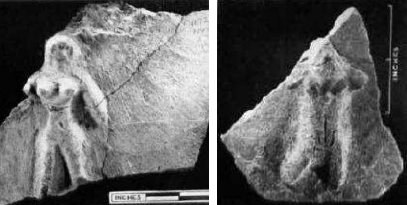

18. Lajja Gauri excavated at Navdatoli, Madhya Pradesh (1000-800 BC)

19. Lajja Gauri from Mathura (300-400 BC)

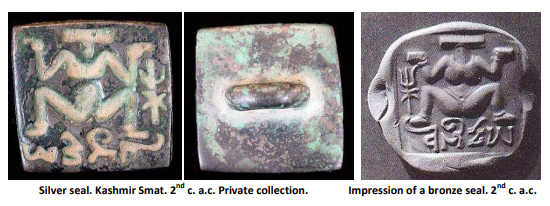

20. The seals of the Kashmir Smat consecrate the Ma Lajja Gauri in the 2nd AD

21. Lajja Gauri from ancient Kushana period of Noth India

22. Lajja Gauri from Chalukya kingdom architecture

23. Lajja Gauri and Vedic Symbolism: Exploring Female Menstruation in Medical Science

In Hindu tradition, several deities are closely associated with menstruation, reflecting its significance in the context of sacred femininity. These deities, such as Parvati, Lajja Gowri, Brahmacharini, Durga, Bhuvaneshwari, Kamakhya, Chandi, and Bhoomi Devi, are understood as various aspects or manifestations of the primordial Shakti or Adya, the cosmic Mother and originator of the universe. Thus, menstruation is deeply revered and celebrated through the worship of these divine forms and the associated festivities.

Lajja Gowri, for instance, symbolises sexuality, fertility, and childbirth. Her iconographic representation often depicts her in a seated posture with open legs and an exposed vulva, symbolising fertility and indirectly linking her to menstruation. A more direct connection to menstruation can be observed in the form of Ma Durga. Durga, manifesting in nine distinct forms, is honoured during the nine nights of Navaratri. These forms include Shailaputri, Brahmacharini, Chandraghanta, Kushmanda, Skandamata, Katyayini, Kaalratri, Mahagauri, and Siddhidhatri. The first five forms hold special significance in various stages of a woman’s life journey.

Shailaputri symbolises childhood, Brahmacharini represents puberty and the onset of menstruation (menarche), Chandraghanta signifies marriage, and Kushmanda and Skandamata are associated with pregnancy and childbirth, respectively. Therefore, Brahmacharini Durga presides over the puberty and menarche phases, specifically worshipped on the second night of Navaratri.

A more intimate and direct correlation with menstruation is found in Ma Bhuvaneshwari, revered as the presiding deity of female menstruation in India. Her worship underscores the sacredness and divine aspect of this natural biological process, highlighting its integral role in the cosmic cycle and the celebration of feminine energy within Hindu culture.

24. Beliefs and Rituals Surrounding Menarche in Dharmashastra Tradition: Insights from Dharmasindhu

In the Dharmashastra tradition, specifically in texts like Dharmasindhu authored by Kashinatha Upadhyaya, there exists a belief regarding the auspiciousness of the onset of menarche, or the first menstruation, for young girls. According to Dharmasindhu, it is deemed inauspicious if menstruation begins during certain months, specific lunar days, or under particular stars. This is interpreted as a sign that the girl may encounter future obstacles, troubles, or disabilities.

The months considered inauspicious for menarche include Chaitra, Jyeshta, Ashadha, Bhadrapada, Kartika, and Pushya in the Hindu calendar. Similarly, Dharmasindhu identifies specific lunar days such as Pratipada (the first day of the lunar month), Chaturthi (the fourth day), Amavasya (the new moon day), and six others as inauspicious. Furthermore, Sunday, Tuesday, and Saturday are considered inauspicious days for the onset of menstruation. Menarche occurring under ten particular stars is also considered inauspicious.

To mitigate these perceived negative effects and ensure the removal of future troubles indicated by inauspicious menarche, Dharmasindhu prescribes a specific ritual known as ‘Bhuvaneshwari Shanti’. This ritual is recommended to be performed after marriage but before Garbhadhana Samskara (the ritual for the conception of a child). The deity invoked in this ritual is Ma Bhuvaneshwari, whose blessings are sought to counteract any potential adverse consequences associated with inauspicious menarche.

25. Ambubachi Festival: Honoring Ma Kamakhya’s Annual Menstruation Ritual in Assam

The Ambubachi festival, celebrated in Assam, honours the famous Ma Kamakhya and her annual menstruation ritual. According to tradition, Ma Kamakhya undergoes menstruation for three days each year, during which time the temple dedicated to her remains closed to allow her to rest. This significant festival occurs during the monsoon season, specifically in the Assamese month of Ahaar, typically falling in June.

During these three days, local agricultural activities are suspended as a mark of respect to Ma Kamakhya, who is also revered as Mother Earth. Daily worship and religious rituals within the temple are halted, reflecting a period of austerity and reverence. The stone representation of the Goddess, a naturally formed Yoni, is covered with a red cloth during this time.

After the Yoni is ceremonially bathed and worshipped on the fourth day, the temple doors are reopened amidst festive celebrations. Devotees receive a special Prasada, which includes a piece of the red cloth that covers the Yoni. This Prasada is considered highly auspicious and purifying due to its association with the Goddess’s menstruation, which is believed to manifest as natural springs within the temple complex.

The Ambubachi festival spans four days and includes elaborate festivities, including a large fair called Ameti. This fair attracts tantric Sadhus, Babas, and devotees from various parts of India. It serves as a platform for showcasing rural crafts and traditional practices, enhancing the cultural richness of the celebration.

The Ambubachi festival is a poignant example of how Hinduism integrates different aspects of menstruation—such as notions of impurity (ashaucha), austerity, rest, and celebration—into a cohesive and revered event. It underscores the deep spiritual significance attached to Ma Kamakhya’s annual menstruation cycle, symbolising fertility, renewal, and the interconnectedness of life within Hindu traditions.

26. Raja Festival in Odisha: Celebrating Menstruation and the Divine Feminine

In Odisha, the Raja festival, celebrated in June, exemplifies the cultural celebration of menstruation, particularly honouring the Earth Ma (Bhu-devi). This Ma is revered under various names, such as Harchandi, Prithibi, Thakurani, Basudha, and Draupadi. Unlike perceptions of menstruation as taboo in some cultures, Raja festival participants view menstruation as a divine and sacred aspect integral to the cycle of life and fertility.

During the Raja festival, both men and women participate in the celebrations. However, women play a central role, as they perceive themselves as integral parts (as has) of the Goddess. The entire festival revolves around honouring and celebrating the feminine aspect of the divine. It serves as a time to recognise and celebrate the creative power and nurturing qualities associated with women, symbolised by the Goddess’s menstruation.

The festival activities include various rituals and customs emphasising the connection between women, fertility, and the Earth Goddess. Women engage in special rituals celebrating their roles as creators and nurturers, echoing the reverence for Ma and her cyclic nature. Traditional games, cultural performances, and community feasts mark the joyous atmosphere of the Raja festival, highlighting the unity and solidarity among women as embodiments of the Goddess.

27. Thriputharattu Festival: Celebrating Ma Parvati’s Menstruation at Chengannur Mahadeva Kshetram

In conclusion, remember that Sanatan, meaning eternal or timeless, represents the eternal light that guides us. Dharma, the path of righteousness and duty, illuminates our journey through life. It is a heritage to be cherished and shared with pride. By embracing and spreading the teachings of Sanatan, we enrich our lives and contribute to humanity’s collective enlightenment.

In the southern state of Kerala, Chengannur Mahadeva Kshetram is renowned for its unique tradition where Ma Parvati (Bhagavati) is believed to undergo menstruation, an event celebrated as the ‘Thriputharattu’ festival. Periodically, the murti (sacred idol) of Ma Parvati at the temple is inspected for any signs of menstrual blood stains by the wife of the Supreme priest of Sabarimala. Upon confirmation of menstruation, the temple announces the commencement of the festival.

During the first three days of the festival, the murti of Ma Parvati is secluded from her husband, Bhagwan Shiva, and given rest in a separate room. This period mirrors the seclusion and rest observed by women during menstruation. Temple women stay outside their rooms at night to provide companionship and support.

On the fourth day, the Ma is taken in a grand procession on a female elephant to the Pamba River for a ritual bath. Following this purificatory bath, she is adorned with elaborate clothes and jewellery, and various ceremonies and rituals are performed to honour her divine presence.

The ‘Thriputharattu’ festival attracts thousands of devotees from across Kerala who gather at Chengannur Mahadeva Kshetram to participate in these sacred rituals and seek blessings from Ma Parvati.

Remember that Sanatan, meaning eternal or timeless, represents the eternal light that guides us. Dharma, the path of righteousness and duty, illuminates our journey through life.

In conclusion, the journey through the narratives of Devi Lajja Gauri and similar goddesses in Hindu mythology reveals a profound tale of cultural appropriation and the imperative to reclaim authenticity. These deities, revered for their association with fertility, creation, and the divine feminine, have endured misinterpretation and misrepresentation. Western lenses, often clouded by colonial biases, have distorted their sacred meanings, reducing them to simplistic and derogatory labels.

Yet, amidst these challenges, there is a growing movement to restore these goddesses to their rightful place in the pantheon of Hindu spirituality. Scholars and devotees advocate for a nuanced understanding rooted in the cultural, historical, and spiritual contexts that birthed these deities. By embracing this approach, we honour the richness of Hindu mythology and recognise the universal themes of fertility, creation, and the eternal feminine that these goddesses embody.

(The story is based on thread on ‘X’ by The Story Teller)

![A Representative image [ANI Photo]](https://organiser.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/representative-image-e1765612818961-120x70.webp)

Comments