When an election happens over seven phases spread over two months; it is bound to kill much of the excitement otherwise expected from West Bengal, where the ruling Trinamool is facing strong anti-incumbency. Given the State’s track record in poll related violence and rigging (referred in political theory as “election machinery” or “electioneering”), phased election has become a practice since 2006. That West Bengal has a long and porous border with Bangladesh adds to the vulnerability. The tempo is significantly down this year at least in Kolkata, districts adjoining to it and parts of South Bengal; when compared to the charged environments of 2019 Lok Sabha or 2021 Assembly elections. And, that makes prediction difficult.

There are some good sides of it. Normally, the arrival of elections in West Bengal is marked by a spike in violence. Dead bodies start piling up during poll season. The body count peaks after the election when central forces are withdrawn. From that perspective, this election season is a little ‘dull’ so far. Hopefully, it remains so. However, we have to wait to reach any conclusion about the effectiveness of the law and order machinery. Political heat is down across the country due to literal disintegration of I.N.D.I coalition, lack of issues – except the vague “democracy in danger” slogan – to the Opposition and, a much-predicted easy win for the Narendra Modi Government.

Nationally, the curiosity is limited to BJP’s showing. Will it get 370 seats? Will it emerge as a force to reckon with in Tamil Nadu and Kerala? In 2019, BJP secured 61 out of 80 seats in Uttar Pradesh. How many more can they add? However, the logic does not apply to West Bengal, which is an outlier in national politics and is under a de-facto single-party rule for nearly half a century. From election in cooperatives, panchayats to Lok Sabha; the ruling party tries to grab everything that comes on its way in Bengal. An Opposition supporter is virtually treated as an ‘enemy,’ often deprived of basic rights. This is the source of political tension and violence. This is also the reason why results in Lok Sabha and Assembly polls always move in the same direction in this state, unlike an Odisha. For all practical purposes, therefore, 2024 Lok Sabha should determine the trend of 2026 Assembly election in Bengal. And, yet the tempo is down. This may partly be a result of the factionalism within BJP, that came up from nowhere to be the second largest party in 2021, with 18 MPs and 77 MLAs. While the old party machinery failed to keep up with the pace, the new entrants did not gel. Opening doors to rotten apples of Trinamool, during 2021 Assembly election, impacted the public perception. Thankfully many of them exited after the poll debacle.

On the brighter side, 2021 election helped BJP to find a mass leader in Suvendu Adhikari. He had defeated the Trinamool supremo and the Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee, from her favourite ground at Nandigram. Adhikari will be BJP’s biggest bet to improve the tally in 2024. The party had exercised much caution in distributing tickets as well. However, it surely lacks the united face that was so evident in 2019. The second problem comes with the non-performance and/or failure to keep party machinery oiled in number of existing seats. In Hooghly, Bankura and Burdwan, BJP may be facing tough challenges from within. Non-performance of MPs is also a serious challenge and may impact results in at least three existing seats in South Bengal. BJP fielded new faces in two such constituencies.

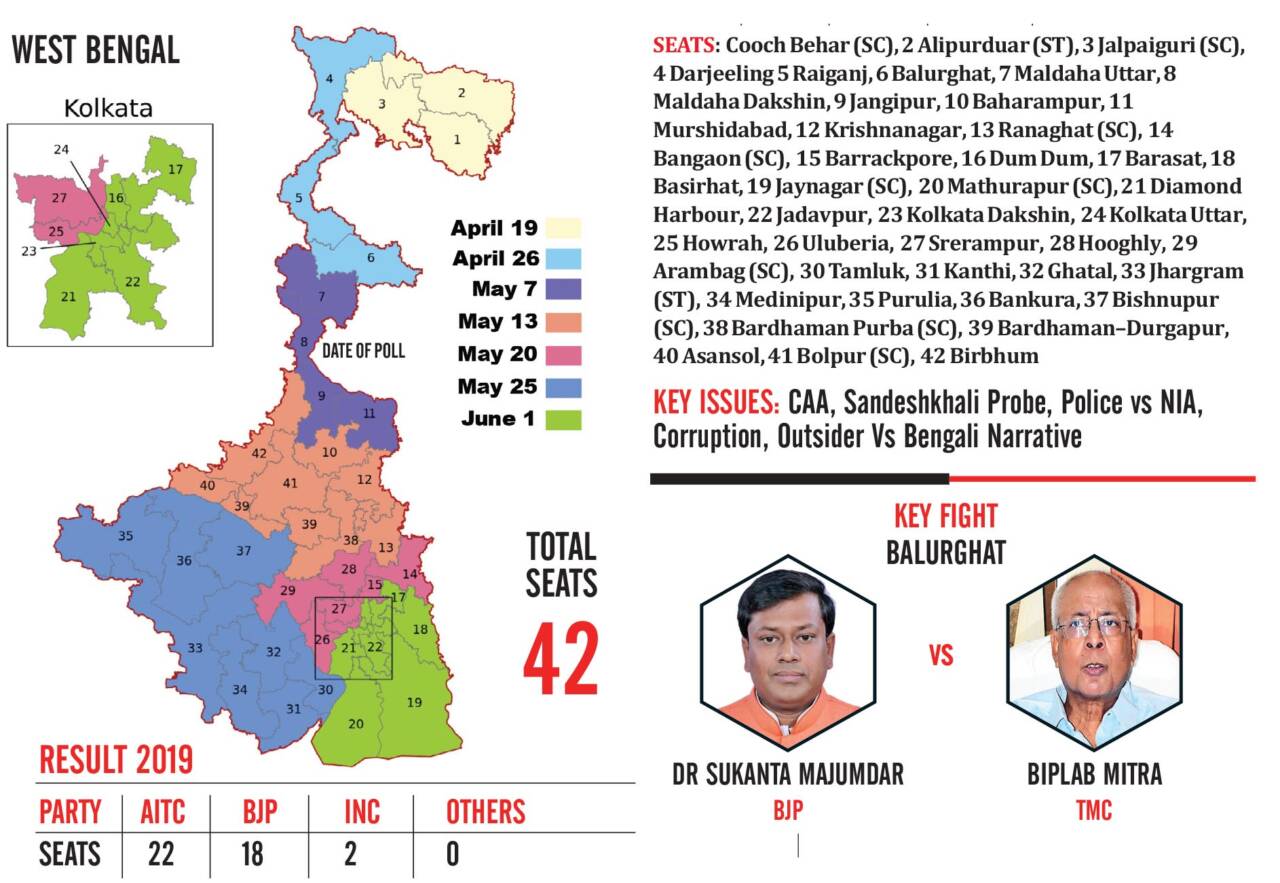

Also, desertion of party supporters and activists to post-poll violence has not gone down well. Many die-hard BJP activists are sitting on the fence this year. All put together the party is not looking as charged up as in 2019. Sustained erosion of Congress and Left has not helped BJP either. Raiganj and Balurghat in North Bengal has 44 and 30 percent Muslim votes respectively. In 2019, Left and Congress together cornered 20 percent vote in Raiganj and 10 percent in Balurgha. BJP won both the seats. Consolidation of Muslim votes from Left and Congress to Trinamool, shifted the balance away from BJP in 2021. In 2019, BJP trailed in three Assembly segments out of seven in Raiganj. In 2021, Trinamool won five Assembly seats with wider margins.

Will these votes return to Congress and Left? There is not much answer to this question. Apparently, both the parties lost the favour of the electorate. Muslims have lots of grievances against Mamata Banerjee Government. Nawsad Siddique’s Indian Secular Front (ISF) fielded candidates in nearly half a dozen seats. But the proof of the pudding will lie in eating. Meanwhile, the usual aggression is missing in Trinamool’s campaign as well. Instead of high voltage public rallies and muscle flexing, the party is more focussed on keeping its faction-ridden organisation together. The party is facing numerous corruption charges. Sandeshkhali episode has made it unpopular even to the Bengali urban elite.

Comments