The Shakti Peeths, integral to Shaktism in Hinduism, are sacred pilgrimage sites associated with the Mata Adi Shakti. Legends link their origins to the self-immolation of Mata Sati and the subsequent division of her body into 51 parts by Vishnu, forming sacred worship sites. While the exact number and locations remain debated, these sites, documented in ancient texts like the Tantra Churamani, the most revered book of the Hindu Shakto sampradaya and Shakti Peetha Stotram, extend beyond India to countries like Bangladesh. This article delves into several Shakti Peeths in Bangladesh, shedding light on their historical significance, the resistance against invaders by Sanatani men and women, heroes who were devotees of these sacred Peeths, and the current state of these revered sites. The revival of these Shakti Peeths is seen as vital for nurturing the roots of Hinduism, echoing the sentiments of Adi Shankaracharya.

Bhabanipur Shakti Peeth

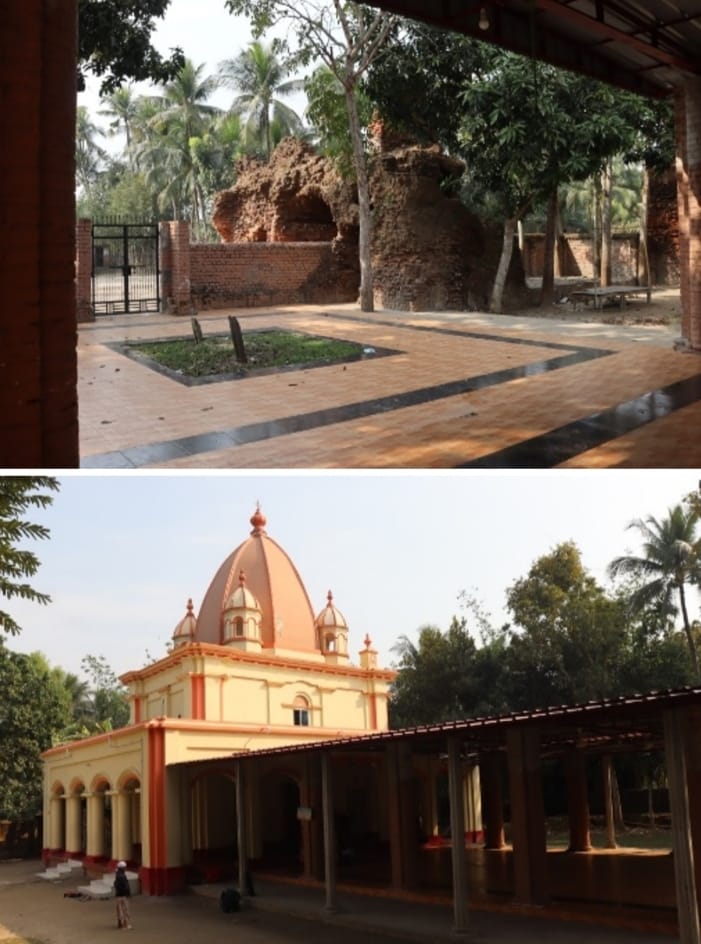

The Bhabanipur Shakti Peeth, nestled in Karatoya, Bangladesh, holds a sacred connection to the Mata Aparna and the Bhairav known as Vaman, symbolising the spot where the left ear of Sati Devi is believed to have fallen. This revered site, located approximately 28 kilometers from Sherpur Upazila in Bogra District, Rajshahi Division, has weathered challenges, including the destruction of its under-construction Guest House by combined forces in 2007. Despite such adversities, the Bhabanipur Temple Renovation, Development, and Management Committee, which has overseen temple activities since 1991, resisted the Archaeological Department’s attempts to assume control of the Peeth. The Bhabanipur Shakti Peeth finds mention in Tantra Churamani (তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি), an ancient and revered book of the Shaktos.

করতোয়াতটে কর্ণে বামে বামনভৈরবঃ । (Kartovatate Karne Bamanbhairava)

অপর্ণা দেবতা যত্র ব্রহ্মরূপাকরোদ্ভবা।। (Aparna Devata Jatra Brahmarupakarodbhava)

(তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি) (Tantra Churamani)

It means Mata Sati’s left ear has fallen in the Shaktipeeth (also a Satipeeth) at Karatoya (present-day Bhabanipur) in Bangladesh, and Bhagwan Baman is the protector here.

The deep historical roots of the Bhabanipur Shakti Peeth intertwine with remarkable figures, with Rani Bhabani emerging as a prominent heroine. Born in 1716 CE, Rani Bhabani assumed the role of queen after her husband’s demise and expanded the Natore estate, a significant zamindari covering a vast portion of Bengal. Faced with the rising influence of regional satraps like Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah, Rani Bhabani courageously defended her kingdom. She led her forces against Siraj ud-Daulah’s army, securing victory and protecting her daughter Tara from being sent to Siraj’s Harem. The Rani’s contributions extended beyond military prowess; during the Great Bengal famine of 1770, she assisted the poor by employing vaidyas at her own expense. Rani Bhabani further supported the early 18th-century war for independence, contributing to the resistance led by Hindu Sanatani Sanyasis. This period, often labelled as a rebellion by the British, witnessed Rani Bhabani’s significant role in funding the war, showcasing her commitment to resisting foreign rule. Post the war of independence, Rani Bhabani continued her impactful contributions, focusing on social reforms. She promoted widow remarriage, advocated for education, and made substantial donations to various educational institutes. Her philanthropic endeavours extended to the construction of the road from Howrah to Varanasi, the Durga Kund Mandir in Varanasi, and contributions to Tarapith, a Hindu Temple town in West Bengal. Despite the British takeover of her kingdom after her death in 1803 CE, Rani Bhabani’s legacy endures through her contributions to Dharma and social betterment. However, the present condition of the Shakti Peeth, to which she was an ardent devotee and made major efforts to preserve and reconstruct, reflects the challenges faced by this historical site, emphasising the importance of restoring it to honour the resilience and sacrifices of those who defended Dharma over the centuries.

Bodeshwari Shakti Peeth

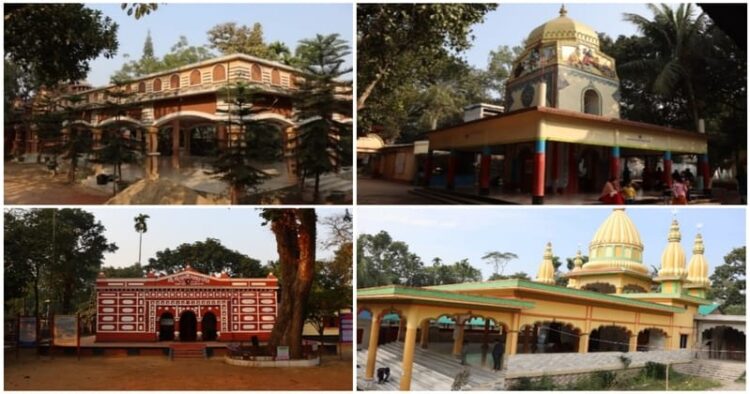

Trisrota Sri Bodeshwari Shaktipeeth, located in Bodeshwari village within Panchagarh district, Bangladesh, stands as a revered spiritual and historical site associated with the Mata Aparna. Re-constructed by King Pran Narayan of Cooch Behar, the temple is situated at the confluence of three rivers: Karatoya, Yamuneshwari, and Buri Teesta. Reports suggest that the temple was built during the Pala period. It is believed this Shaktipeeth marks the sacred spot where Mata Sati’s ankle part fell. Despite its proximity to the international border with India, the site remains a non-restricted zone and hosts significant religious events, including “Pavitra Mahalaya” and “Akshay Tritiya.” With the Karatoya River flowing nearby, the pilgrimage site attracts traditional pilgrims during Mahalaya to perform tarpan/shradham for their ancestors. Unfortunately, the holy Mahalaya day of 2022 witnessed a tragic incident when a boat capsised on the way to the temple, resulting in the loss of 71 lives, commemorated by the “Mahalaya Akshay Smriti Smarnik” shrine.

The Shaktipeeth, supported by the Raj Family of Cooch Behar, holds historical significance dating back to the heroic resistance led by Raja Pran Narayan against the Mughals. In 1661 CE, Pran Narayan captured Dhaka but faced defeat, taking refuge near the Shaktipeeth. Through prayers to the Mata, he launched guerilla warfare against the Mughals and, in just three years, successfully regained his kingdom, renovating the Shaktipeeth as an offering to the Mata.

The enduring legacy of Pran Narayan continued through his son and the Ahom rulers, contributing to the victory of Lachit Burphukan in the Battle of Saraighat in 1671 CE. Despite changes brought by Mughal rule, including the induction of Animists into the Hindu fold, the heroic efforts of Pran Narayan ensured the survival of Hindus in the region. The Shaktipeeth, lacking clear boundaries, parking facilities, and proper amenities, remains a cultural capital for local Hindus. The potential for a Kartarpur-type corridor near the international border holds strategic importance, fostering connections among Hindus and ensuring the safety of the chicken corridor. Renovating the Shaktipeeth aligns with the rich and heroic history, connecting Barendra Hindus, Rajbogshis, and Hindus beyond Cooch Behar and Jalpaiguri, who connect with this glorious history of resistance against the invaders.

Jeshoreshwari Shakti Peeth

Jeshoreshwari Shakti Peeth, also known as Jeshoreshwari Kali Temple, is situated in Ishwaripur, a village in the Shyamnagar upazila of Satkhira district, Bangladesh. Despite its present location, which is closer to the Khulna district, it was originally associated with the Jessore district before the region’s reorganisation. To reach the Kali temple, one must travel to Satkhira Sadar, then proceed to Tollygounge in Shyamnagar and finally reach Bongshipur Gram. The Jeshoreshwari Shakti Peeth finds mention in Tantra Churamani (তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি) too.

যশোরে পাণিপদ্মঞ্চ দেবতা যশোরেশ্বরী । (Panipadmancha deity Jashoreshwari in Jessore)

চণ্ডশ্চ ভৈরবো যত্র তত্র সিদ্ধির্ন সংশয় ॥ (Chandashcha Bhairbo Jatra Tatra Siddhirn Samshayo)

(তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি) (Tantra Churamani)

Tantra Churamani mentions that Mata Sati’s palm fell at Jessore Satipeeth (also a Shaktipeeth) in Bangladesh and that Mata here is Jeshoreshwari and Rakshak Bhairava is Chanda Bhairava.

The temple gained attention in 2021 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited, donating a golden crown to Mata Kali. Legend has it that a luminant ray of light led the General of Maharaja Pratapaditya to discover a stone carved in the form of a human palm. Pratapaditya, becoming a patron of the Shakti Peeth, constructed the Jeshoreshwari Kali Temple. His courageous resistance against invaders, notably during the Mughal era, exemplifies the essence of the Shakti Peeth. Pratapaditya’s rule during Akbar’s time saw him as a vassal of the Mughals, but his reluctance to assist them resulted in the seizure of his capital. His defence, however, succumbed to a sudden attack, leading to his capture and eventual death in Varanasi while being taken to Delhi in a cage as a captive. Despite controversies surrounding Pratapaditya’s rule, including encounters with the Portuguese, his legacy reflects the Hindu renaissance and resistance against imperialist forces. He was responsible for building a united Hindu army consisting of Hindus of all castes, including the Bagdis (Barga Kshatriyas), today a Scheduled Caste sub-group, as defenders of his kingdom and of Hindu values against the invaders.

The Shakti Peeth faces encroachment challenges today, with individuals claiming to be Hindus asserting control over the temple property. The temple’s debottar property has been encroached upon by land mafias and Islamists, and the premises require urgent renovation to preserve its authenticity. The strategic and geopolitical importance of this Shakti Peeth, near the international border, suggests the potential for a corridor to connect devotees, commemorating Raja Pratapaditya and fostering a renewed sense of pride and patriotism.

Sugandha Shakti Peeth (Barishal)

Barishal, situated in the southern part of Bangladesh, holds historical importance due to its association with the Sugandha River, next to which lies a Shakti Peeth. It is believed to be the sacred site where the nose of Mata Sati fell. The district has strong connections to Hindu zamindars, influential landowners and patrons of the Shakti Peeth. Across the river stands the revered Bhairav, considered by some as the actual Shakti Peeth, despite lacking a formal structure. Our team learned that the Ugra Tara and Kosti Pathor in the Shakti Peeth faced looting before 1971, with unfortunate events recurring during the turmoil in 1971, leading to subsequent reconstruction and installation of the present murti.

Encroachments are noted, and land leasing is common, with the Mondir committee receiving nominal rent. The construction of the Padma Bridge has made the Shakti Peeth easily accessible. Despite challenges, Barishal continues to preserve its cultural and religious heritage, featuring notable landmarks like the Sitala Mandir and Kali Mandir. The Mool Mandir, lacking amenities like a parking lot, stands within defined boundaries. The ongoing construction of the Athithishala adds to the evolving landscape, and the Langar Khana symbolises the enduring nature of the place. Tara Bari, dedicated to Ugra Tara, boasts a marble floor, reflecting the community’s commitment to preserving cultural heritage. The Barishal Shakti Peeth, one of the 51 Shakti Peeths, signifies the cultural unity of Hindus worldwide, emphasising the importance of preserving this sacred site.

The Sugandha Shakti Peeth too finds mention in Tantra Churamani

সুগন্ধায়াং নাসিকা মে দেবস্ত্র্যম্বকভৈরবঃ ॥ (Sugandayang nasika me Devastryambaka Bhairava)

সুন্দরী সা মহাদেবী সুনন্দা তত্র দেবতা । (Sundari Sa Mahadevi Sunanda Tatra Deity)

(তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি) (Tantra Churamani)

The Tantra Churamani, the main text of Shaktism, says that Mata Sati’s nose fell on the Satipeeth in Sugandha (present-day Barishal) in Bangladesh, and here the Rakshak Bhairava is Tryambaka and the Mata is Sunandasundari Devi.

Sita Kund Shakti Peeth (Chittagong)

Chittagong Zila, nestled in the southeastern part of Bangladesh, is characterised by its rich cultural and religious diversity, with notable sites like Kumira and Chandranath. Sita Kunda Upazilla within this district houses Sita Kundu, acknowledged as both a Shakti Peeth and a sacred pilgrimage site, sparking debates about its status as a Sati Peeth. Regardless, for Hindus, it holds profound religious significance. Chandranath Parbat, revered as a self-manifested form of Shiva, stands as a picturesque hill with spiritual importance for Hindus. Our team’s ascent to its summit revealed its enchanting allure. Ancient texts link Sita Kund to Darbhanga Maharaj, comparing it to the spiritual strength of Kailash.

The Shakti Peeth at Chittagong, derived from Chattal / Chattala, also finds mention in Tantra Churamani (তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি).

চট্টলে দক্ষবাহুর্মে ভৈরবঞ্চন্দ্রশেখরঃ ॥ (Bhairavanchandrasekhar in Chattle Dakshbahurme)

ব্যক্তরূপা ভগবতী ভবানী যত্র দেবতা । (Personification of Bhagwati Bhavani Jatro Deity.)

বিশেষতঃ কলিয়ুগে বসামি চন্দ্রশেখরে ॥ (Especially in Kali Yuga Basami Chandrashekhar)

(তন্ত্র চূড়ামণি) (Tantra Churamani)

It means Devi Bhavani’s Satipeeth is located in Chittagong (Chattal). Here the right arm of the Mata fell, and the protector of this place is Chandrasekhara. In this place Bhagwan Shiva resides in direct (visible) form in Kali Yuga.

The divine stone statue of Bhagavan Shiv in his Bhairav manifestation, made of costly coral, adds to the spiritual ambience. However, challenges like open defecation, plastic pollution, and limited accessibility detract from the pilgrim experience. Despite its spiritual history, the Peeth is gradually transforming into a tourist spot, losing its religious essence. The temple’s old structure has been demolished, the guest house is absent, toilets are in poor condition, and the missing boundary wall raises concerns. The absence of recognisable Debosthan signs and difficult accessibility further diminish its sanctity. Sita Kundu’s history, intertwined with legends of Bhagwan Ram’s visit during Sita’s abduction and its association with the Tripura royal family, underscores its significance. However, threats such as encroachments, non-Dharmic businesses, and an encroaching ecopark jeopardise its sanctity. Around 3000 acres of Peeth property are lost, raising concerns about toll payments. The involvement of a Shrine Board acknowledges Sita Kundu’s importance among Hindus, despite challenges like corruption and land encroachment. Despite these challenges, the shrine remains a revered destination, emphasising its enduring spiritual significance for followers of various Hindu sects, necessitating immediate renovation to strengthen the beliefs of many Hindus.

Kala Gul Shakti Peeth (Sylhet)

Sylhet, historically known as Srihotto, encompasses a profound cultural and religious heritage, with Jainpur Briva Desh hosting Sri Saila Parvat in Kalagul. The Shri Mahalakshmi Bhairabi Griba Maha Peetha on the Sri Saila Parvat stands as one of the Shakti Peeths, situated in Jainpur village, Dakshin Surma, near Gotatikar, approximately 3 km South East of Sylhet town in Bangladesh. It is the sacred site where the neck of the Hindu Mata Sati is believed to have fallen.

In the Shakti Peeth Strotam, written by Adi Shankaracharya in between 8th to 9th century CE, it is mentioned that the neck of the Mata Sati fell at Sri Saila. This is given in the verses in Sanskrit.

श्रीशैले च मम ग्रीवा महालक्ष्मीस्तु देवता ।

भैरवः सम्बरानन्दो देशो देशो व्यवस्थितः ॥ ३३॥

It means my neck is on the Śrīśaila, and the deity of the Mata of fortune is Mahālakṣmī.

Bhirava, Sambarananda, is situated in every place. 33॥

Devotees revere the Mata under the name Mahalakshmi, and the Bhairav form worshipped here is known as Sambaranand. The main deity is a colossal stone murti, and the temple’s vast property was once under the ownership of Devi Prasad Das Munshi, a prominent Zamindar during the British period. The property, classified as the deity’s endowment, faced challenges like encroachment, leading to legal battles that reached the Supreme Court. Despite being a Gazetted Zamindar, the temple’s land disputes persisted, with a main road even cutting through the sacred grounds. The Shiv Bari, where Bhairav resides atop a tila, has witnessed significant encroachment. During the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, rioters attempted to destroy the temple but failed. Moving deeper into the jungle and tea gardens, the narrative shifts to Maharaja Gour Govinda, the last Hindu king of the region, around 800 years ago, and his connection to Ishan Kunj, believed to be Kala Gul or Griva Peeth. Gour Govinda’s tila houses Hatokeshwar temple, and the Patra community, loyal subjects of the king, still call themselves Gour Govindo projas or subjects. The tila bears traces of temples dedicated to Kangssho Nishudon, Hatokeshwar, Hattonath, Hottokali, Raghuveer, and Mata Mahalaxmi. Our team met the members of the Patra community. The Patra community, once Pujaris, today considers themselves to be Kshatriyas and defenders of the Shakti Peeth. They abandoned Upanayana but continued to maintain cultural practices in reverence to Gour Govinda. Even 800 years after the demise of the last Hindu king, the Patra community’s belief in being spiritual warriors of the Kingdom and the Mata is crucial for the survival of Hindu Sanatan Dharma amid tremendous challenges. The spiritual energy of this remote Shakti Peeth remains palpable despite challenges faced by the temple and its surrounding areas, with the Patras playing a vital role in preserving the historical and spiritual legacy of Sylhet. Being next to Assam, an international corridor like the Kartarpur corridor can be quite helpful.

Kanaighat Shaktipeeth (Bamojonga/Jaintia)

In Sylhet, another place considered to be a Shakti Peeth is Bamojonga in Jaintia (Jayanti). This is very close to Meghalaya. The place was maintained by the Jaintiya Maharaj family, kin of Gour Govindo. They had made it a Debottar (Spiritual) Land. The temple committee here is not fixed. Locals complained that the committee is filled with Hindu haters promoting beef eating. No ancient structure of Bamojonga exists. Many Hindu sects recognise this as Sati Peeth and Shakti Peeth. This is in a remote area with no motorable road. The Guest house and parking lots are missing. The pond is there but encroached. The Jaintiya Raja symbols are there. Important political and religious leaders visited this place, as seen in the visitor’s book. The left thigh of Mata Sati is said to have fallen at Jaintia Shaktipeeth. Hence, it is also known as Bamojonga.

Dakhin Surma

Shri Mahalakshmi Bhairabi Griba Maha Peeth, located in Joinpur village near Gotatikar, Dakshin Surma, about 3 km South East of Sylhet town, is among the sacred sites known as Shakti Peeths. This site is where the neck (Griba) of the Hindu Mata Sati fell, and she is revered as Mahalakshmi, with the Bhairav form known as Sambaranand.

Conclusion

Our team on the ground in Bangladesh took great pains to visit many of the Shakti Peeths, often in remote locations. They did it out of their love for Hindu Sanatana Dharma and on a voluntary basis. They spoke to locals about the place and its associated history of Kings and patrons who have preserved these sites. A most interesting outcome of these discussions is the stories of heroes in history who saw these Shakti Peeths as a spiritual source of unbounded energy to resist the invaders despite personal sacrifices. The Shakti Peeths, therefore, need to be preserved, and international corridors must be created for the pilgrims, wherever possible. It will add to the preservation of the Hindu Sanatan civilisation in Bharat’s neighbourhood.

Comments