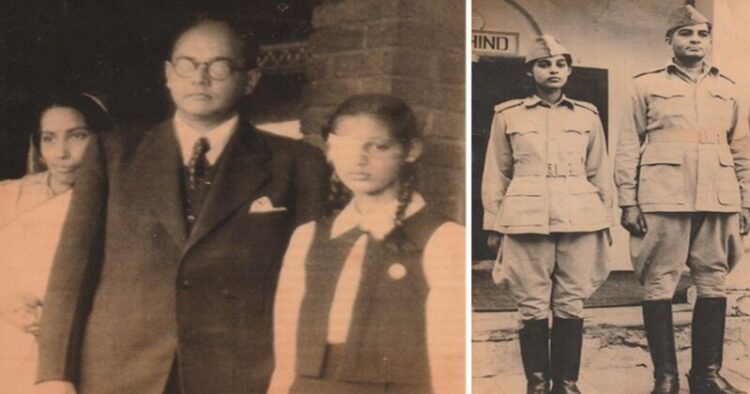

This is an inspiring story about a 95-year-old former INA soldier named Asha-san. She was a lieutenant of the Rani Jhansi Regiment under Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Azad Hind Fauj and is the grandniece of Deshabandhu Chittaranjan Das. Her journey is a testament to her courage and determination, and it is no surprise that she has been hailed as ‘India’s daughter’.

Eager to delve deeper into the inspiring life of Lieutenant Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry and excited to meet one of the few INA veterans alive, my friends and I from St. Michael’s High School, Patna decided to meet her. Our decision was fueled by the compelling narrative painted in her gripping book, The War Diary of Asha-san: From Tokyo to Netaji’s Indian National Army.

As we entered her presence, excitement buzzed in the air. The experience unfolded with a cascade of observations that left an indelible mark on our memories. Our eyes eagerly turned to a graceful figure – none other than Asha-san from the formidable Rani of Jhansi Regiment of Netaji Subhas Bose’s INA.

Lieutenant Bharati ‘Asha’ Sahay Choudhry, her silver tresses impeccably styled, basked in the gentle glow of the late morning sun. With a spirited rendition of “Kadam kadam badhaye ja,” the lieutenant infused life into the air. We were in awe, seeing the 95-year-old still be able to speak three languages and write. Her performance was nothing short of a radiant spectacle, casting a timeless spell on all of us.

Singing seems to come so naturally to her. She appears to possess a natural talent for singing. During a chance encounter, we were able to hear her hum a tune called “Shubh sukh chain ki barkha barse,” which was once used as the national anthem of the Provisional Government of Free India led by Netaji. She sang this particular tune when they arrived in Kolkata in 1946 at the Hindustan Park home of her grandmother Urmila Devi, who was the sister of Chittaranjan Das. She sang on many other occasions as well, such as when her college gave her a send-off as she prepared to join the theatre of war. She sang:

Subhas ji, Subhas ji, woh jane Hind aa gaye

Hain naaz jispe Hind ko, woh shaan Hind aa gaye

Soldiers of the Azad Hind Fauj created this piece to honour Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and welcome him to Singapore on July 3, 1943.

Asha, who was 15 years old, lived in Japan during the Second World War. She was attracted to patriotism more by the thrust of the bayonet than by a song. She was still too young to join the fray. However, when she became 17, she was prepared to join the Rani Jhansi Regiment and fight for India’s freedom.

Our experience with Asha-san turned out to be a fortunate encounter in three ways. Firstly, her son Sanjay Choudhry had done a commendable job of collecting and organising relevant information from archives and memories of people associated with Asha-san’s life in Japan. Secondly, the translator of The War Diary, Tanvi Srivastava, a talented short story writer and Asha-san’s granddaughter-in-law, was very articulate and effective in her communication. And lastly, Asha-san herself, intervened in a gentle yet firm manner, like a cherry blossom tendril, to provide her own recollection of important events.

As we reflect on Japan during the war years, it is the song that resonates with us more than the singer. A brave teenager found the courage to endure hardship and a shortage of food. Regular sirens sent them rushing into the trenches, while education was acquired bit by bit, but a strong sense of patriotism overrode it all.

The War Diary of Asha-san has gone through various versions. During the Second World War, Asha-san wrote it in Japanese. She was born in Kobe in 1928, and when she returned to India, she translated it into Hindi with the help of her parents and her Hindi professor. Writing on scraps of paper and frayed notebooks was a challenging task, but she persevered, documenting every emotion, challenge, adversity, meetings with great leaders, and interactions with brave Japanese who were willing to sacrifice their lives from 1943 to 1947. The diary was serialised in the popular Hindi pictorial weekly Dharmyug in 1973 and later compiled into a book called Asha-san ki Subhas Diary. Sanjay republished it in 2011.

“I have been writing in my diary since my early childhood. Bombs may fall, typhoons may swirl, yet I cannot sleep without writing in my diary,” Asha-san says.

Tanvi stumbled upon a hidden gem amidst the dusty shelves of her home library: Asha San’s War Diary. As she delved into its pages, she found herself transported to a world eerily reminiscent of Anne Frank’s Diary, penned during the tumultuous 1940s. Despite the geographical and cultural disparities, both Asha and Anne shared a common thread—they poured their souls into the pages of their diaries, each navigating their own trials and tribulations.

Little did Tanvi know that this chance encounter would ignite a passion project during the unprecedented times of the Covid era. With two mischievous little ones underfoot, she began working on the formidable task of translating Asha San’s words, breathing new life into a story that had long remained silent on her bookshelf. Through the chaos of lockdowns and homeschooling, Tanvi found herself entangled in the words of a fellow young soul grappling with wartime life’s complexities. Her grandmother-in-law’s story, she believes, “seems to transcend time, space and language”.

Asha-san’s love for nature and her Japanese ethos of perfection and etiquette are often mentioned by Tanvi — “an Indian girl growing up in Kobe and Tokyo, living a life steeped in Japanese culture, nationalism and ethos”.

A young woman, aged 17, sets out on a journey of self-discovery, leaving behind her home and family. She has always been vocal about her respect for military officers and often salutes them as her colleagues, proudly exclaiming, “Jai Hind”.

She recalls how 1945 was a turning point for her in more ways than one. In February, Netaji agreed to enlist her in the army. She got the opportunity she had been waiting for the last two years. One can only admire her mother Sati Sahay’s patriotism “. I have already handed over your father and uncle to Mother India. Now you are no longer my daughter, but India’s daughter..: After a perilous journey of three months, Asha-san and her father reached Bangkok, where the Rani Jhansi Regiment was stationed. The diary entries of this period give detailed descriptions of their journey and the travails of the cadets in the camp.

It’s worth mentioning that Asha-san’s parents are Anand Mohan Sahay and Sati Sen Sahay. Anand Mohan Sahay served as a political advisor to Netaji during his arrival in Japan and later joined the cabinet of the Provisional Government of Azad Hind as a secretary, making South East Asia the primary centre of his political activities. He embraced nationalism at a young age and worked closely with Dr Rajendra Prasad, Mahatma Gandhi, and later Rashbehari Bose in Japan. He played a vital role in setting up several branches of the Indian Independence League across Asia.

In 1903, Sati Sen Sahay was born as the niece of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das. She actively participated in the Non-Cooperation Movement. During her time at Santiniketan, where she studied under Rabindranath Tagore, she imbibed a deep sense of nature, the arts, and nationalism. Possessing an independent mindset, she played a pivotal role in instilling a sense of patriotism in Asha from a young age.

After their marriage, they immediately departed for Japan. Despite the scarcity of food during those challenging times, Sati Sen was driven by nationalism and supported Anand Sahay’s work by contributing to a journal called Voice of India, which was published in both English and Japanese. With her unique skills that she acquired in Santiniketan, she even designed currency notes for the Azad Hind Government. Sati was always a silent warrior, whether it was in her beliefs or how she managed to make ends meet and provide for her family during tough times. Sati Sahay’s brave patriotism had her telling her daughter Asha, “I have already handed over your father and uncle to Mother India. Now, you are no longer my daughter, but India’s daughter…”

They were to understand hunger and also, in the same breath, stoicism, politeness, and the ability to want to face danger and death, which were so many qualities that the Japanese had and which the Indians were to imbibe and ingest.

Anand Mohan Sahay writes about daughter Asha: “During and before the war we resided in Japan, where we had an uncommon and unique opportunity to work for India’s Independence. Asha was also witness to these experiences. …The war transformed Asha from being a delicate emotional girl to someone who was spirited, a girl who could face any fires, any storms.”

Asha-san writes ruefully: “In 1945, I was a newly commissioned lieutenant in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment of the INA. I was anxious and eager to reach the frontline as soon as possible. But it was not my fate to look the enemy in the eye. My rifle did not fire any bullets; my bayonet did not slash the arteries of any enemies. An entire organisation….built by patriots, fell apart in a matter of weeks. First, with the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then, the Japanese surrendered. Then, the death of Netaji. My war ended before it started. War is silence. War is doubt. War is not knowing.”

Lieutenant Asha, who had received training in Bangkok, had a different experience upon returning to India. She was imprisoned after the Japanese surrender. In 1946, she reunited with her father and they returned to India, along with Asha’s uncle, Satyadev Sahay. Satyadev Sahay was the director of the Intelligence Bureau, INA. Together, they travelled across India to spread the word about the efforts of the INA towards the liberation of India.

The family did not attend the Independence Day celebrations as they believed that the nation was divided. Asha-san shared a story with us that her mother had told her about the Indians in Kobe who had decided to hoist the Tricolour from their homes on January 26, 1935. At that time, it was considered a bold move. On that morning, Sati rushed out of her house with a matchbox in hand to check if every household had hoisted the Tricolour. All but three had done so, and Sati went to those homes and set the Union Jack on fire. When the authorities received complaints, the Japanese surprisingly did not reprimand the patriots. Sati was praised and honoured for her courageous act by both the Japanese and the Indians in Kobe.

Having the courage and compassion to establish oneself in a new country with a fresh perspective requires a great deal of determination. Ironically, Asha-san experienced a cultural shock in the homeland that she so fervently dreamt of freeing. ‘In my dreams, I had tasted the moist earth of India, and now I walk on her soil. But not freely. India was not free, and I gradually realised I, too, was shackled by a new set of customs and superstitions. The deeper we entered India, the more rigid the rules became.” This is what happened when she got married to a doctor and started a new life with their children, getting involved in social work and joining various clubs. The comfort of wearing a kimono was replaced by saris, and the tatami was abandoned. However, nothing could stop her, even years later, when Tanvi saw her husband’s grandmother enter the dining room carrying a heavy saucepan full of rice. This was when she was introduced to the art of sushi-making, and she demonstrated her expertise with precision, using a bowl of salted water, three bamboo mats, several nori sheets, finely sliced vegetables, a sharp knife, and a mound of vinegared rice. They were able to create several rows of maki together.

Asha-san maintained a strong connection with Japan. She worked as an interpreter for a Japanese Mandir in Gaya and visited Japan twice. In 2009, she attended the 90th anniversary celebration of Showa Women’s University, where she held the distinction of being the oldest living alumna.

Her life was guided by Buddhist philosophy and Japanese stoicism, which helped her overcome various challenges. Presently, she resides in Patna with her son Sanjay and daughter-in-law Ratna. Despite her age, Asha-san’s mind remains sharp, and she continues to be a source of support for her family.

As school students, it was truly awe-inspiring for us to witness her presence, considering she is one of the few living INA veterans among us. She says, fear? What is that? I don’t know if something called fear ever existed in my heart!

Comments