In the heart of Varanasi lies a historical treasure – the Gyanvapi complex, comprising the Kashi Vishwanath temple. The ongoing legal battle surrounding this sacred site has taken an intriguing turn as James Prinsep’s 200-year-old lithographic map has emerged as a key piece of evidence.

James Prinsep, a British numismatist and archaeologist, left an indelible mark on India’s historiography. His contributions include deciphering the Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts, shedding light on Emperor Ashoka’s reign, and making significant strides in the understanding of ancient Indian history. Prinsep’s legacy is commemorated at the Prinsep Ghat in Kolkata, named after him in recognition of his groundbreaking work.

Prinsep’s connection with Varanasi becomes pivotal in the context of the Gyanvapi case. During his 10-year tenure in Varanasi from 1820 to 1830, he not only built the city’s underground sewage system, still operational today, but also restored the Alamgir Mosque, commissioned by Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1669. His most noteworthy contribution, however, lies in the detailed map and book titled ‘Benares Illustrated: A Series of Drawings,’ published in 1831.

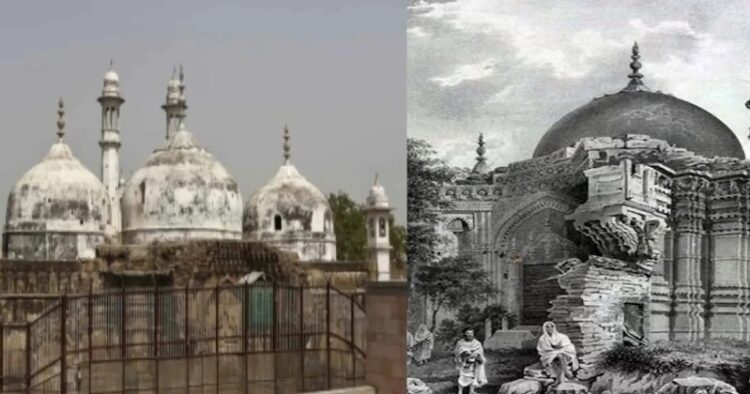

This book, enriched with lithographs depicting various facets of Varanasi, will play a crucial role in the legal proceedings concerning the Gyanvapi complex. Prinsep meticulously illustrated the Manikarnika Ghat, Brahma Ghat, porocession of the Tazeeas, and Hindu Nach Girls, offering a comprehensive visual record of the city. Importantly, he delved into the architecture of the original Vishweshwar temple, now the Gyanvapi mosque, in his exploration of Varanasi’s cultural and religious landscape.

In ‘Benares Illustrated,’ Prinsep provides a historical account of how Aurangzeb’s religious zeal led to the conversion of the Kashi Vishweshwar temple into the Gyanvapi mosque. His observations expose Aurangzeb’s bigotry, narrating how the materials from the demolished temple were repurposed for the construction of the mosque.

Prinsep writes, “The bigotry of Aurungzeb did not allow many vestiges of this more ancient style to remain. In 1660, for some trifling resistance to the imposition of a capitation tax, he took occasion to demolish the principal Shiwalas and constructed mosques with the same materials and upon the same foundations, leaving portions of the ancient walls exposed here and there as evidence of the indignity to which the Hindu religion had been subjected.”

The detailed account provided by Prinsep in 1831 has now become a crucial element in the ongoing legal battle over the Gyanvapi complex. The Hindu side aims to utilize the historical evidence presented by Prinsep to establish the origin and transformation of the sacred site, emphasising the religious and cultural significance of the original Vishweshwar temple.

As the legal proceedings unfold, Prinsep’s 200-year-old map serves not only as a historical artefact but as a key witness, shedding light on the complex history of the Gyanvapi site. The juxtaposition of past and present through Prinsep’s meticulous documentation adds a new layer to the ongoing discourse surrounding religious and cultural heritage in India.

Comments