Geography and history have uncanny ways of amalgamating, being intertwined in shaping each other’s contours. Great statesmen have seldom forgotten this fact, and it behoves us to revisit the words of Lord Curzon, Viceroy of British India, around the turn of the previous century, when he professed “Turkestan, Afghanistan, Transcaspia and Persia, to many these names breathe only a sense of utter remoteness or a memory of strange vicissitudes. To me I confess, they are the pieces of a chessboard upon which is being played out a game for the domination of the world”.

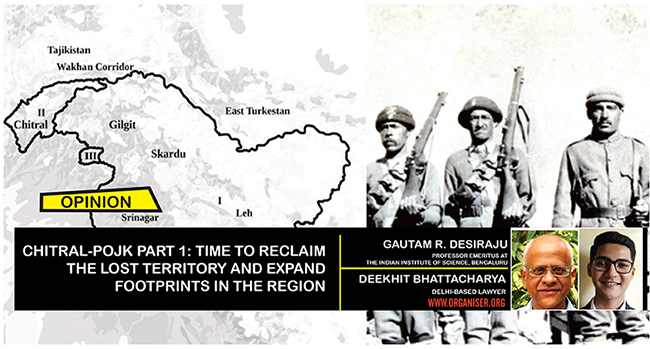

In the remotest part of this remote region lies a 14,850 sq km domain called Chitral, which has a staggering average elevation of 2,500 m. Bounded by some of the highest mountains in the world and yet crisscrossed by ancient trade routes which connected civilisations across millenia, this small tract offers land connections from India to Afghanistan, East Turkestan, Tibet and Central Asia. In a world of fluid political developments, Chitral is at the geographical nerve centre of the Eurasian landmass, and in this sense has the potential to influence tectonic shifts in global history. To quote an actual distance from current maps, Chitral lies a mere 20 km from Tajikistan and is separated from it by a narrow strip of Afghan land called the Wakhan corridor. In terms of natural resources, it is an incomparable source of granite, precious stones and water. As a new great game between global powers pans out in Central Asia, Bharat must not only resume pressing its rightful, legal claim on Chitral as being Bharatiya territory, but also correct its maps to reflect the same. Bharat’s territory, and its perspective on its relationship with broader Central Asia, both remain incomplete unless Chitral is expressly included in Bharat’s official cartography.

Chitral’s inclusion within the erstwhile J&K State

Chitral has historically been at the crossroads of Bharatiya, Sino-Tibetan, and Afghan spheres of influence. Its cultural and political relations with Bharat can be traced back to at least the 3rd Century A.D., when it was a part of Kanishka’s domains. Vis-à-vis our legal claims over Chitral, one can conclusively trace the dots back to at least 1864, when it sent its first documented tribute to the Maharaja of Jammu & Kashmir.

By 1860, the dominant regional power, i.e. Gilgit, was conquered by Jammu & Kashmir, with Gilgit’s erstwhile vassals and tributaries now declaring Jammu & Kashmir as their suzerain. As the Maharaja’s forces marched closer to Chitral, the then Afghan king was also beginning to threaten Chitral’s political existence. Meanwhile, Chitral’s then overlord, Kashgar Khanate centred in today’s East Turkestan, had considerably weakened. Caught between rival expansionists, and with a weakening guarantor of their independence, Chitral formally broke its tributary relations with Kashgar in 1871. It thereafter renewed its annual tribute (Nazrana) to Jammu & Kashmir by 1876. Jammu & Kashmir’s position as Chitral’s suzerain was put into writing in 1877, whereby a formal agreement was drawn up with Jammu & Kashmir; Chitral was thus incorporated as a part of the Maharaja’s domains.

The British had begun to take keen interest in Bharat’s northern frontiers by then. Russia forcefully sent an uninvited diplomatic mission to Afghanistan in 1878, and this ultimately triggered the Second Anglo-Afghan War. Jammu & Kashmir’s constant expansion northwards made the British nervous, and they feared Jammu & Kashmir would enter into untoward understandings with other powers, even perhaps Russia. An Officer on Special Duty (OSD) was rapidly dispatched to Gilgit, and the 1877 agreement was replaced by a British-supervised treaty between Jammu & Kashmir and Chitral in 1878. The very first Article of this treaty reads: “I engage that I will always sincerely endeavour to obey and execute the orders of His Highness the Maharaja, the Wali of Jammu & Kashmir… that I will present the following ‘nuzzerans’ to his Highness annually as an acknowledgement of his paramount power…”. Thus, Chitral securely continued within the fold of the Maharaja’s kingdom.

Britain’s failed schemes to snatch Chitral

As Jammu & Kashmir’s intricate web of subsidiary states within its domains (like Chitral) grew, the British wished to assume direct involvement at the frontiers of Jammu & Kashmir. Chitral had achieved particular salience, as the British feared that it could become a possible route for a Russian invasion of India. The above OSD was upgraded to become a full-fledged political agent stationed at Gilgit, and began to give effect to Britain’s colonial schemes by superintending Jammu & Kashmir’s subsidiary states such as Chitral and Hunza. This political agent, to further distance the Maharaja’s court from the region, made the Maharaja hand over a large part of Gilgit to be administered by the political agent nominally on behalf of Jammu & Kashmir. This land came to be called the Gilgit Agency. Incidentally, Chitral, too, was within the ambit of the Political Agent stationed at Gilgit.

In 1892, Chitral faced a succession crisis, and a tribal Pashtun force rebelled against Jammu & Kashmir. The British could get back control of the situation only in 1895, and were disturbed to learn that the Russians had, in the interim, planned to take over Chitral had Britain failed. Thus, Britain chose to separate Koh, Yasin, Ghizar, and Ishkoman from Chitral’s territory in 1897 and transferred their supervision from the relatively distant Gilgit Agency to the nearby and more approachable Agency of Dir and Swat (informally known as the Malakand Agency) in today’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Yet, despite attempted designs to fabricate the independence of Koh, Yasin, Ghizar, and Ishkoman from Jammu & Kashmir, the British Resident in Kashmir was forced to express his helplessness in the matter in 1930, where he bluntly stated that “On every map of these regions which has ever been issued, officially or otherwise, they are shown as being within the borders of Kashmir”.

“A large part of Jammu and Kashmir is under the occupation of Pakistan. People on other side are seeing that people are living their lives peacefully in J-K. People living in POJK going through a lot of suffering and they will raise demand to go with Bharat ” — Rajnath Singh, Defence Minister

In 1902, Chitral-proper’s supervision was given over to the North West Frontier Province, which also came to encompass the Agency of Dir and Swat. Nonetheless, in 1914, a delimitation exercise was carried out between Chitral and the rest of Jammu & Kashmir, under British stewardship. The original legal position was sustained—the first Article of the corresponding Agreement read “I acknowledge the suzerainty of His Highness the Maharaja of Kashmir and Jammu and in token thereof will resume the token payment of the annual “Nazrana”…”. Thus, the change in administrative oversight from Gilgit to the North West Frontier Province did not change the legal position of Chitral being a constituent of Jammu & Kashmir. However, the British had begun to find it desirable to somehow (even informally) sever Chitral from Jammu & Kashmir and bring it directly under British jurisdiction. Just a year prior, in 1913, the British had arm-twisted the Maharaja to withdraw his own troops from Gilgit, and replaced them with the British-officered Gilgit Scouts.

The Soviets revived Russia’s long standing expansion into Central Asia, and this renewed British involvement in the Gilgit-Baltistan region. Simultaneously, the British were also keen on weakening the Maharaja’s writ, for example by fanning domestic flames such as those which came to the fore in 1931 with Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s movement. The British were actively plotting the separation of entities overseen by the Gilgit Agency from Jammu & Kashmir, only to come up with repeated legal frustrations. When the delicate pen of legality failed to subserve British interests, they resorted to realpolitik: the disturbances spearheaded by Abdullah were feted with words such as “with the spread of disaffection in his (i.e., Maharaja’s) State, it will be necessary for him to depend more upon the British Government than he has in the past. This (i.e., increased autonomy for the Political Agent at Gilgit and loosening control of the Maharaja) will presumably be the more advisable in the outlying areas (i.e., Gilgit Agency) now under consideration where he has not the same direct control as in the internal portion of the State”. Under duress and with his grasp over State affairs deteriorating, the Maharaja was forced to grant the British the remainder of Gilgit under a 60 year lease for administration under the Gilgit Agency in 1932, and give the Political Agent at Gilgit a nigh-free hand.

The inclusion of Chitral in Bharat’s maps, as also extending Gilgit’s boundaries to their full lawful extent, is critical in shaping Bharat’s engagement with adjacent regions

The British had covertly made it a strategic objective to legally detach Chitral from Jammu & Kashmir by at least 1937. The passage of the Government of India Act, 1935, thrust an ex-post facto Westphalian description onto Indian States for whom the concept of the Westphalian Nation-State was quite alien.2 Thus, when the Act defined the political and territorial extent of Indian States, the British were keen to find legal loopholes. In this regard, a 1938 note authored by LCL Griffin, the former political agent at Gilgit, who had by then become a Secretary to the Government of (British) India in the Political Department, is instructive.

The then External Affairs Department had secretly asked the Political Department as to whether Chitral could be discreetly excluded from the State of Jammu & Kashmir upon the State’s accession to the Federation which the Government of India Act, 1935, intended to set up. The Note was a part of a long, convoluted series of to-and-fros between various officials within the Government. LCL Griffin, whose views came to subdue those which diverged from his own, was unequivocal that the legal position was that Chitral squarely fell within the domains of the State of Jammu & Kashmir. He went on to say “that there can be no doubt looking to the definite acknowledgment of suzerainty in the Agreement of 1914 [Aitchison, Vol. XI, page 428], attested by the Assistant Political Agent, Chitral, and to the definition of “ Indian State” in Section 311 (1), that Chitral must be regarded for the purposes of the Government of India, Act, 1935, as included in the Kashmir State… The question put by the Court would presumably be the narrow one of fact: “Is the Chitral State under the suzerainty of the Ruler of Jammu and Kashmir?” The only reply which the Crown Representative could give to this would be an affirmative one and the Court, looking to the definition of “ Indian State” in Section 311 (1), would be bound, in spite of the fact that the population of Chitral is not included in the population figures against Kashmir in the Table of Seats in Schedule I, to find that Kashmir’s accession included Chitral.”. These views were reiterated in another note authored by Griffin a few months later.

The Secretary of State for India in London concurred in response to the note, stating wryly that “As regards the definition of an Indian State in Section 311(1), we agree with your view that as the Act stands at present Kashmir’s accession might well be held to include Chitral and would certainly be held to include Hunza, Nagar, and other areas in the Gilgit Agency which it will be desirable to exclude from Kashmir for the purposes of Federation.” The Secretary of State proposed an amendment to the Act to expressly allow for exclusions of territories from a State upon accession based on royal direction (i.e., the British setup within India).

Such a proposed amendment to the Act went nowhere, in no small part thanks to VP Menon and BN Rau, who included their terse view in the correspondence that such an amendment would cause “nervousness among the Rulers” and “other incidental difficulties”. Likewise, letters drafted in 1940 to fraudulently ‘inform’ Kashmir that Chitral and other constituents in the Gilgit region were somehow not a part of Kashmir, to compel the Maharaja into not enumerating these territories as parts of his domain and thus for the British to usurp the same, were put in cold storage. With World War II erupting, the sheer disturbance surrounding increased militancy from the independence movement, and the resultant increased dependency upon Princely States to act as storm barriers shielding the British from nationalist fervour, an amendment of such nature was rendered unviable.

Comments