India’s diversity has been a matter of matter pride for the country. However, while diversity may be a quintessential aspect of the cultural and spiritual fabric of a country, the same cannot be the expectation when it comes to the legal and policy framework.

With a disparate legal framework, the expectations and aspirations of the people also begin to vary from one individual to another. Over time, these varying expectations lead to an isolationist mindset that eventually mutates into sentiments against national unity.

Examples from around the world showcase that in line with democratic principles, the laws governing citizens of any country should be uniform. Uniform Civil Code (UCC) aims to achieve in India a regime of equal application of laws to all the citizens of the country, thereby ending any discrimination that may exist due to peculiarities of personal laws.

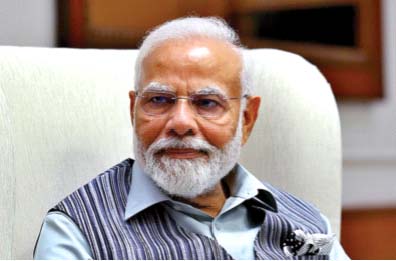

“These days, we are seeing that people are being instigated in the name of UCC. You tell me, if in the same family there is one law for one member and another law for a second member, will that household be able to function? Can one run the country with such dual system?” – Narendra Modi, Prime Minister

However, over the last few months, people and political leaders who wish to benefit from chaos and disharmony in India have propagated the idea that the Uniform Civil Code is a Majoritarian government’s expressionist agenda.

These baseless arguments have pushed popular discourse towards a more religious outlook – where the UCC is being viewed not as legal reform, but as a measure to curtail religious freedoms. This document attempts to decode and put to rest this manufactured propaganda and present UCC as the legal reform it is intended as.

The Premise

A common thread amongst these opposing views is that UCC is a means to suppress religious freedoms and apply a state-sponsored majoritarian rule on the nation’s minorities. Ironically, this cannot be further from the truth as the very idea of a UCC is to end discriminatory practices and bring in uniformity before the law – as is clearly instructed by the Indian Constitution. No other reform can be considered more democratic and secular than the UCC. The UCC will not only ensure that every citizen has equal rights, but it will also lay the foundation of a nation that is unified– in geography and law.

The idea that “I am considered differently” begins to form as individual aspirations are curtailed with respect to the separate personal law that applies to the individual in question. Over time, these separate exceptions give rise to a demand for a separate legal system and, eventually, a separate constitution; or, worse, a separate state.

If the rights that are guaranteed and enshrined in the Indian Constitution are fundamental to every individual as long as they are an Indian citizen – the legal remedies and resolutions available to every citizen must also be fundamentally the same for everyone. The colonial doctrine of divide and rule propagated to weaken the Indian revolutionary movement and laid the seed of a system that benefits by bringing in the idea of inequality and disharmony.

Today, India is poised at a historic moment in time – a moment where our decisions may either set us on the right track or hurl us into the abyss of disharmony and isolated mindset that may irreversibly harm the nation’s unity. India, today, has a chance to reorient the direction we move in collectively – the decision, therefore, lies with India and her people.

Ensuring Equality

Today, India’s women, for example, are leading the nation towards the goal of development and progress – as mothers, teachers, entrepreneurs, scientists, and sentinels of the borders. Then, why must women not be provided with equal rights and judicial remedies as are enjoyed by men in society? Or worse, why must women from one community be subjected to fundamentally patriarchal laws while women from another community – living side by side – have access to legal remedies and guidance governed by progressive principles?

The present personal laws, differing vastly for each religious community, are largely discriminatory towards women. For example, women do not have equal rights to inheritance, and in some cases, no right to inheritance. Post-Independence, attempts to protect women’s rights have been made through piecemeal legislation like the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act, 2005.

However, even despite such amendments, the property of a Hindu widow is directly transferred to her husband’s family, unlike what occurs with male members. Additionally, Muslim laws permit polygamy, thus often putting women in disadvantageous and unfair positions.

Who stands where?

There have been mixed responses to the uniform civil code (UCC) from various political parties. There have been expressions of support and rejection as well. Here we list which shows who stands where on UCC:

Congress

The Congress party has led the charge in the rejection of the UCC, calling it unnecessary and undesirable.

Congress leader Jairam Ramesh said that UCC was “neither necessary nor desirable at this stage”. Congress leader Meem Afzal dubbed UCC as “DCC” that stands for “dividing civil code”. He said, “This is not UCC, this is DCC-Dividing Civil Code. UCC is not the agenda, rather the agenda is to divide the people of the country.”

However, there have been supportive and moderate voices too within Congress. Himachal Pradesh minister and Congress leader Vikramaditya Singh extended “full support” for UCC but urged against “politicisation” and questioned its timing.

Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)

Rajya Sabha MP Manoj Kumar Jha of RJD said that UCC was “actually neither desirable nor necessary” and added that it was being used “as an instrument for your dog-whistle politics”.

Janata Dal (United)

The Janata Dal-United (JD-U) referred to previous statements on UCC, pointing out that JD (U) leader and Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar in 2017 said that “UCC must be seen as a measure of reform for people’s welfare, not as a ‘political instrumentality’ to be hurriedly imposed against their wishes and without consultations.

The Left parties

CPI General Secretary D Raja said that the UCC targets one particular community and added that the Parliament should lead this exercise, not the law panel.

The CPM has opposed UCC from the last round of consultations in 2017, calling it politically motivated.

Aam Aadmi Party (AAP)

The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) has come out as the main Opposition party that has supported UCC. The party gave “in-principle” support to UCC. The AAP said that consultations should be held with all the stakeholders on the issue of UCC.

Shiv Sena (UBT)

The Uddhav Thackeray’s faction of Shiv Sena has also supported UCC. Senior faction leader Sanjay Raut said, “Let there be a debate. We have always supported the Uniform Civil Code. If a debate is happening on it…in the country… let there be a debate…we will see what the opinion of the people is.”

What is also relevant to consider is that the UCC will not only create a uniform code for Muslims, Christians and Hindus, but also for other smaller religious communities that exist in India, such as, for instance, the Parsi community. Therefore, even the differential treatment meted out to women under the laws of such communities will be weeded out. For instance, Parsi laws as they stand today state that Parsi women who marry outside of the Parsi community lose their right to inheritance and even their right to enter their place of worship, i.e., fire temples.

The Only Way Forward

The only way to ensure a universal and timely change in the manner in which laws protect women’s rights is to implement a UCC that will simultaneously create equal laws that will apply to all religions across the board and thus get rid of orthodox dogmas that exist under the guise of religion.

67 per cent of Muslim women support UCC: Survey

A recent survey conducted among Muslim women showed that at least 67.2 per cent of Muslim women support uniform laws for marriage, divorce, adoption and inheritance. The survey took the opinion of over 8000 Muslim women from different parts of the country of varying ages from 18 to 65. The surveyed women were further divided based on their level of education, ranging from illiterate to postgraduate. As per the survey, 76.5 per cent of Muslim women were against polygamy and do not want Muslim men to have the right to have four wives. 68 per cent of graduate Muslim women supported the idea of a uniform law over personal law. In the age group of 45 and above, 59 per cent of women were in favour of a uniform law while 69 per cent were in favour, in the age group of 18-44, as per the survey conducted by News18.

In India, Family laws are mostly based on religious affiliations and are thus governed by personal status laws. Some of these laws are state-enacted statutes, while others are based on customary practices or religious precepts. As these diverse laws are confusing and contradictory, and rooted in outdated precepts, when India adopted its Constitution in 1950, a provision regarding the enactment of a Uniform Civil Code to govern family relationships was included in the Directive Principle of State Policy.

MR Masani, Hansa Mehta and Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, who were part of the sub-committee who were tasked with the responsibility of including Fundamental Rights had noted the following: “One of the factors that has kept India back from advancing into nationhood has been the existence of personal laws based on religion which keep the nation divided into watertight compartments in many aspects of life. We are of the view that a uniform civil code should be guaranteed to the Indian people within a period of five to ten years..’

Ideologues have deliberately used UCC as an instrument with which to beat minorities, and especially Muslims, through the fabricated threat of a majoritarian homogenising principle destructive of the precious identity markers seen in the existing diversity of personal laws. Hence, the UCC must be viewed as a legal system that enshrines parity, equality, equity and liberty within India’s legal framework. Therefore, administrative energies are essentially a trade-off, owing to which the State benefits increasingly if its attention is diverted to more productive and worthwhile aspects rather than futile tasks.

Comments