The controversy over Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is nothing but political and vote bank politics has certainly marred the social welfare legislation for decades now in independent India. There is, of course, vested interest in a particular community also.

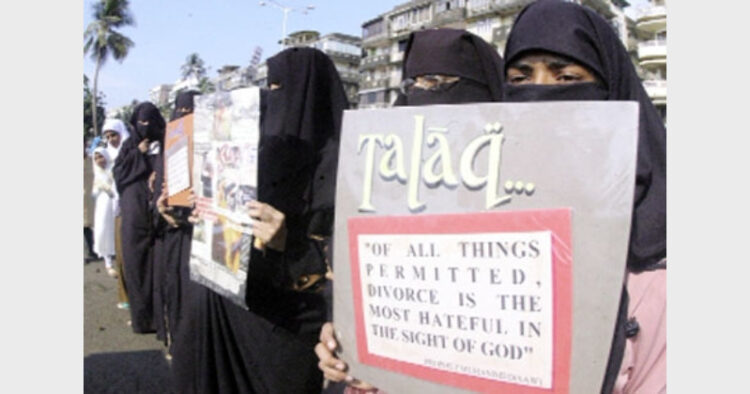

UCC does not mean a person should perform, during marriage, saptapadi (the sacred seven steps) or nikah or any other ritual. Nor a person would be compelled to marry in a certain manner. But after marriage nobody can just say talaq and abandon a woman. So, UCC is not just about marriage where personal laws or customs can play a role. Say for example, a Janjati person can marry according to a particular Janjati customs and practices, but, when that person divorces, can he just abandon his wife?

UCC does not certainly say marry in a particular manner. It is only about divorce, maintenance, inheritance, custody of children, adoption and remarriage. The UCC, as enshrined in the Article 44 of the Constitution of India, is nothing but empowerment of Indian women, irrespective of religion, language, place of birth, race, colour, etc. For, the “State”, under Article 15 of the Constitution “shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them”.

If one carefully reads the above, on the basis of “sex” too the State cannot discriminate any citizen. But willy-nilly, Article 44, somehow, may be in the wisdom of the founding Fathers of our Constitution, went to find a place in the “Directive Principles of State Policy” chapter of the Constitution, where as Article 15 remains in the Fundamental Rights Chapter of the Constitution.

Now what is Uniform Civil Code (UCC)? Matters like marriage may not come under it as it depends on the customs and rites of an individual’s religion. But divorce, maintenance, adoption, custody of children and even dignity of the gender and gender justice is UCC, which is nothing but empowerment of women.

I was a law student in the year 1985 when the decision of the Supreme Court in Shah Bano case came. “A Common Civil Code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to law which having conflicting ideologies”, the SC then had observed. Hell broke loose. I was travelling to my native village in Tamil Nadu from Delhi (I was a law student of Delhi University’s Campus Law Centre) and travel by train took (still takes) about three nights, two days and a morning. It was a ‘mini Bharat Darshan’ as the train used to travel through about seven states. I could see protest meetings, especially by Muslims, at every State and on reaching my native village, the same night, there was a protest meeting by the Muslim community with copies of the judgment torn off and burnt. My village is a Muslim majority village. I thought for a while, only as a rational law student: “what is wrong with the judgement?” After all, Shah Bano who was given the irrevocable triple talaq was not given any maintenance and left to fend for herself. Under Section 125 Criminal Procedure Code (Cr.P.C.) petition, known as the maintenance case in common man’s language, she was ordered to be given Rs. 500 as alimony. Even that amount, in 1985, was not enough for a woman to keep herself up and live with dignity, for, Article 21 which guarantees Right to Life, by interpretation in various judgments of the various High Courts and the Supreme Court, the final court of the country, is held to be Right to Life includes Right to Life with Dignity.

Then 10 years later, in 1995, as an accredited Supreme Court correspondent of The Telegraph I reported Justice Kuldeep Singh’s judgment in what came to be known as the Sarala Mudgal case. “It appears that…the rulers of the day are not in a mood to retrieve Article 44 from the cold storage where it is lying since 1949,” Justice Singh wrote in that judgment “requesting” the Government of the day to consider implementing Article 44 of the Constitution of India. Later, Justice KT Thomas of the Supreme Court, now retired, called for Uniform Civil Code for gender equality and gender justice. In July last year the Supreme Court again favoured UCC in a case of an unwed Christian mother who challenged the Delhi High Court order to reveal the name of the father of her child when she sought guardianship of the child. In a passport case it was held that Mother’s name was enough to get a passport issued for her child.

The Law Commission has in the past in several reports recommended for the same in different words. However, it has been argued that Article 44 of the Constitution is “Directive Principles” and hence un-enforceable. But look at the language “The State ‘Shall’” which is mandatory. So the ruling party now need not even “look for a debate”. It need not go for vote bank politics. Although the issue has been politicised since the Constituent Assembly. Dr Ambedkar wanted this provision though he had scant respect for Hindu law as in his opinion upper caste Hindus would dominate Independent India. The provision was thus put to cold storage under a “deceptively” worded “directive principles of State Policy”. When a government wants to implement a non-enforceable it becomes like right to education, right to know, etc. all are directive principles.

(The writer is a senior journalist and writes on legal issues)

Comments