The recent installation of Sengol, an emblem of royalty, justice, and power, in the new Parliament building serves as a poignant reminder of the illustrious Chola dynasty. However, the current state of history textbooks in post-independence India fails to offer a comprehensive understanding of the rich tapestry of our past. Instead, the curriculum focuses on the memorisation of the genealogy of Mughals and a systematic list of British rulers, neglecting the enduring legacies of the Cholas and other Indian dynasties.

Regrettably, the names of these influential rulers and their remarkable achievements are unfamiliar to many students, teachers, and even enlightened individuals in our country.

The Chola dynasty, established around 300 BC, held sway for approximately 2,300 years, leaving an indelible mark from the 9th to the 13th century. The annals of history, including Ashoka’s inscriptions, Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, Katyayana’s Vartika, Sangam literature, texts by Saiva saints, Buddhist texts like Mahavansha, and numerous inscriptions in Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada, along with contemporary foreign accounts, provide authentic insights into the glorious history of the Cholas.

The dynasty experienced a revival during the reign of Vijayalaya (848-871 AD) and saw the rule of approximately 20 kings spanning over four and a half centuries (848-1279 AD). Prominent rulers such as Aditya I, Parantaka I, Parantaka II, Rajaraja I, Rajendra Chola I, Rajadhiraja I, Kulottunga I, Vikram Chola, Kulottunga II, Rajaraja II, Rajadhiraja II, Kulottunga III, Rajaraja III, and Rajendra Chola III made significant contributions.

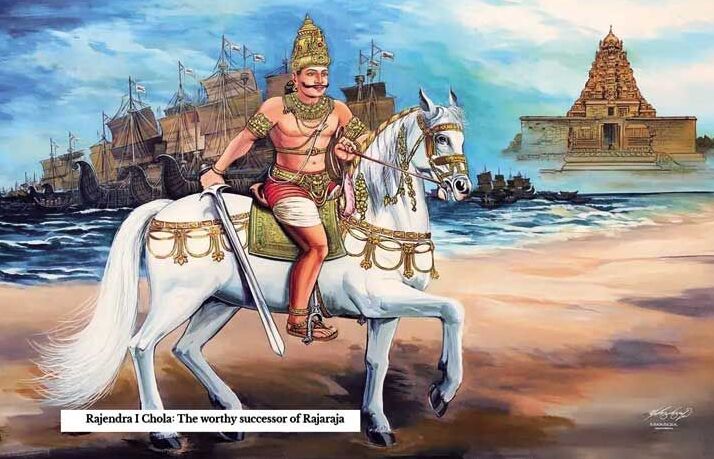

Among them, Rajaraja I (985-1014 AD) and Rajendra I (1014-1044 AD) stood as the most majestic and powerful kings of the Chola dynasty. Under their reign, the Chola Empire expanded its influence from South Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Karnataka to encompass present-day Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Burma, Vietnam, Thailand, Maldives, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Cambodia, and beyond. Recognizing the importance of maritime routes, the Cholas dominated battles at sea, boasting a navy that surpassed those of the English, French, and Portuguese.

With over 1,000 warships and more than a million soldiers, the Chola navy established supremacy over the Bay of Bengal, earning it the ancient moniker ‘Chola Lake.’ Notably, women were also part of their naval forces, actively participating in battles. The Chola navy comprised four primary divisions: Dharani, akin to modern destroyers; Lula, comparable to small warships; Vajra, capable of swift attacks like modern warships; and Thirisdai, formidable warships armed with devastating weapons. The Cholas’ advanced and sophisticated navy nearly a millennium ago is a testament to their strategic foresight and power. The Chola army, known as Chaturangini, consisted of infantry, archers, cavalry, and elephant units.

The Chola dynasty’s administration was renowned for its meticulous organization and efficient governance, as evidenced by various inscriptions. At the apex of the state stood the king, who ruled with the aid of ministers and state officials, forming the supreme authority. The bureaucracy consisted of two classes of officials: the higher class known as “perundanam” and the lower class known as “shirudanam.” To ensure effective oversight, officers called “Kankani” were appointed to supervise and control local officers on behalf of the central department.

From a governance standpoint, the Chola kingdom was divided into several administrative units known as “mandals.” These mandals were further subdivided into smaller units such as Kottam, Valnadu, Nadu, Kurram, and Gramam. The entire land was meticulously surveyed, measured, and categorized into tax-paying and tax-free territories. Nagarams, which were assemblies dominated by the merchant class, played a significant role in the governance of certain areas. Village councils, known as “ur” or “sabha,” held sway over local administration. The executive council of these sabhas, called “aduganam,” was elected from the general public based on merit for fixed terms. According to records from Uttarmerur, village governance was carried out by five sub-committees of the sabha.

The sabhas enjoyed considerable autonomy, with minimal interference from the king in their functioning. To ensure smooth operations, a highly efficient and well-organized committee system known as “Variam” was established, adhering to the rules of the constitution, to oversee the work of sabhas. In addition to village and caste assemblies, the state also established courts for the administration of justice.

These courts relied on evidence from social systems, documents, and witnesses to make decisions. The harmonious combination of highly efficient local self-government and a well-structured bureaucracy was a prominent feature of Chola rule. Various collective organisations catered to different aspects of local life and worked cooperatively with one another. It is not unfair to assert that the administration of the Cholas exhibited traits that can be likened to today’s democratic and locally autonomous governance.

The Chola dynasty’s administration stands as a testament to their commitment to effective governance, decentralized decision-making, and inclusive participation. By studying and appreciating their administrative systems, we can draw valuable lessons for contemporary governance and emphasize the enduring relevance of the Cholas’ governance model.

Despite claims made by some southern cine stars, the historical evidence overwhelmingly supports the fact that the Chola rulers were devout followers of Hinduism, particularly Lord Shiva. They exhibited qualities of generosity, tolerance, and kindness towards their subjects like other Hindu kings. Jains, Buddhists, Parsis and Christians also had equal rights in his kingdom. It is important to dispel any misconceptions or prejudices that suggest otherwise.

The Cholas left an indelible mark on history through their architectural achievements, particularly in temple construction. The Brihadisvara Temple in Tanjore, the Airavatesvara Temple in Darasuram, and the Gangaikonda Cholapuram Temple are exceptional examples of intricate carvings and awe-inspiring architecture.

The Brihadisvara Temple was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, followed by the Airavatesvara Temple in 2004. Notably, the Brihadisvara Temple is the only temple in the world entirely made of granite, attracting countless visitors with its grandeur, architectural splendour, and central dome. Standing at a height of approximately 66 meters and spanning thirteen storeys, the temple is dedicated to the worship of Bhagwan Shiva. It houses a rich treasury of sculptures, iconography, paintings, dance, music, jewellery, and engravings, showcasing excellence in various artistic disciplines such as architecture, stone and copper craftsmanship. The temple also boasts exquisite Sanskrit and Tamil epigraphs and calligraphy. One unique feature of the Brihadisvara Temple is that the shadow of its dome never touches the ground.

At the summit, a gold urn rests upon a stone estimated to weigh 2200 manas (88 tonnes), crafted from a single stone. The temple’s name, Brihadeeswarar, aptly captures the magnificence of the colossal Shivalinga installed within it. Upon entering the temple, visitors encounter a square pavilion within the gopuram, where a 6-meter-long, 2.6-meter-wide, and 3.7-meter-high statue of Nandi, the sacred bull, sits on a platform. This Nandi statue is the second-largest monolithic Nandi sculpture in India.

The Airavatesvara Temple, dedicated to Lord Shiva, derives its name from the white elephant Airavata, Indra’s celestial mount, who worshipped Lord Shiva at this very site. This temple, too, showcases remarkable artistic and architectural craftsmanship, featuring magnificent stone carvings. Located in the Ariyalur district of Tamil Nadu, Gangaikonda Cholapuram was constructed in 1035 AD by Rajendra Chola I. After successfully conquering territories along the Ganges River in northern India, Rajendra Chola I earned the title “Gangaikonda Chola” as the conqueror of the Ganges.

The idols within this temple are of exceptional quality, with the Shivalinga crafted from a single rock. The Chola dynasty’s bronze sculptures are considered among the finest in the world. Masterpieces such as the Chola bronze icons of Bhogashakti and Subrahmanya showcase their remarkable artistic skill.

The Nataraja sculpture, depicting Lord Shiva in the cosmic dance pose of Tandava, exemplifies the excellence achieved in Chola sculpture. Additionally, the Chola artists produced notable representations of Lord Shiva in various forms, Lord Vishnu with Brahma, Saptamatrika, Lakshmi and Bhudevi, Shri Ram and Mata Sita with their retinues, as well as depictions of Shaivite saints and Shri Krishna’s divine dance of Kaliyadaman. These remarkable cultural and artistic achievements of the Chola dynasty serve as a testament to their deep-rooted Hindu beliefs, their patronage of the arts.

The Chola kings displayed exceptional foresight in the realm of irrigation, recognizing its vital importance for agricultural prosperity. They undertook extensive initiatives to enhance irrigation systems, such as digging wells, ponds, and reservoirs, and constructing stone dams to control the flow of rivers. Karikal Chola, for instance, constructed a dam on the Kaveri River, while Rajendra Chola I excavated a massive lake near Gangaikonda Cholapuram, with a 16-mile-long dam.

Elaborate arrangements were made to channel water into these reservoirs from multiple sources, including rivers, employing stone systems and canals to ensure efficient utilization of water resources for irrigation purposes. Moreover, the Chola kings also recognised the significance of smooth transportation networks for the convenience of trade and communication.

They constructed wide highways and river ghats, facilitating the movement of goods and people across their kingdom. In summary, the Chola kings made unparalleled contributions to various domains, including governance, arts, architecture, literature, and culture, as well as the construction of buildings and roads. Their endeavours in irrigation and infrastructure development continue to be admired for their foresight and impact on the region’s prosperity.

But the limited coverage of the contributions made by the Cholas and other Indian dynasties in history textbooks is a cause for concern. The focus of our schools, colleges and universities on Delhi-centric history and the achievements of foreign invaders is unfortunate. To truly understand the holistic and complete history of India, there is an urgent need for a radical change in the content of history textbooks and courses.

It is important that all the glorious chapters of the past, including the Cholas, Chalukyas, Palas, Pratiharas, Pallavas, Paramaras, Maitraka, Rashtrakuta, Vakataka, Karkota, Kalinga, Kakatiya, Satavahana, Vijayanagara, Odair, Ahom, Naga, Sikh dynasties, and other influential states, are studied in detail. These studies should encompass various aspects, such as the methods of governance, diplomatic relations with other states and countries, trade partnerships, business policies and conditions, commercial routes, military structures, strategic strategies, victory travels, and their contributions to art, dharma, society, literature, and culture. By delving into these areas, we can gain a comprehensive understanding of the rich and glorious history of India.

Comments