In 1893, when the twenty-one year old Aurobindo Ghosh returned to India, he couldn’t even speak Bengali, his mother tongue. By then, he had spent fourteen of his formative years in England, having distinguished himself academically—first at St. Paul’s school, London, and later at King’s College, Cambridge. However, over the next two decades, Sri Aurobindo came to represent the spirit of Indian patriotism, both in theory and praxis; he was to become the most prominent face of Bharat’s yearnings for freedom. And by the time he left for Pondicherry in 1910, he had set firmly into place not just the ideals and connotations of our nationalism, but also its objectives and methods. Such was the sheer force and efficacy of his strategy that all those who came after him, including Gandhi, could not help resorting to them.

Put plainly, Sri Aurobindo was arguably the greatest and certainly among the earliest thinkers of India’s complete decolonisation. However, his swift rise to astronomical prominence as well as his lasting legacy, when viewed against the backdrop of his life in England, appears rather baffling. This begs a pertinent question, the answer to which will unpack the very essence of Sri Aurobindo’s anti-colonial thoughts: how come a Victorian gentleman, trained on English soil, succeeds in conquering our country’s imagination?

Three Schools of Thought in 19th Century Bengal

In the late 19th century Bengal, to which Aurobindo returned, one comes across three schools of thoughts on Bharat’s intellectual and political awakening. The first school, as represented by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and his ardent follower Rabindranath Tagore, advocates cultural assimilation and empathy between the East and the West. To them, Bharat and England should meet as equals and capitalise on their intertwined political ties to forge deeper sympathies. This tendency triggered politics of reform, petitioning, and eventually, the moderate faction within the Congress. The second school, as typified by the likes of Michael Madhusudan Dutta and Bengal’s English-speaking professionals—like Dr Krishna Dhan Ghosh, the anglicised father of Sri Aurobindo—looked upon English presence in India as fortuitous. To them, conditions of colonisation presented an opportunity to radically restructure Indian society in the light of Western and Christian thoughts. Naturally, they responded in ways that may reek of unqualified surrender. While Dutta converted to Christianity and spent a lifetime singing paeans to Greek and English literature, Dr Ghosh took his three sons—including a seven years old Aurobindo—to England, put them in the care of an English clergyman, and forbade them from making contact with anything Indian.

If Vivekanand described God as the sum total of all humanity, Aurobindo argues that nation itself is the clearest manifestation of that divinity

The third school of thought, championed with aplomb by the likes of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Swami Vivekanand and Sri Aurobindo, believed that India had something profound to offer to the world, particularly to the morally bankrupt West. They had utmost faith in our ancient scriptures and the pan-Bharat religiosity our sacred texts animated. However, in order to provide intellectual and spiritual leadership to the world, at first, Bharat much smash the shackles of political servitude. Further, for unfettering our political destiny, the country must rely on its core resource—faith, religious fervor, and the spirit of sacrifice and renunciation of our sages. In other words, Bharat had to live by its age-old wisdom, enshrined in Vedas and Upanishads, embodied by its monks and mystics.

Nation as Shakti, Patriot as Sanyasi

In this order of things, nation is not just a lifeless geopolitical territory to be won, guarded and defended against enemies; it becomes the summation of the life-forces of all those who live in it. Nation emerges as a source of their nourishment, a benevolent goddess who provides for her inhabitants, just as a mother provides for her children. In other words, nation becomes the one true subject of their devotion. ‘What is a nation?’ asks Aurobindo rhetorically. ‘It is a mighty Shakti, composed of all the Shaktis of all the millions of units that make up the nation,’ he explains.

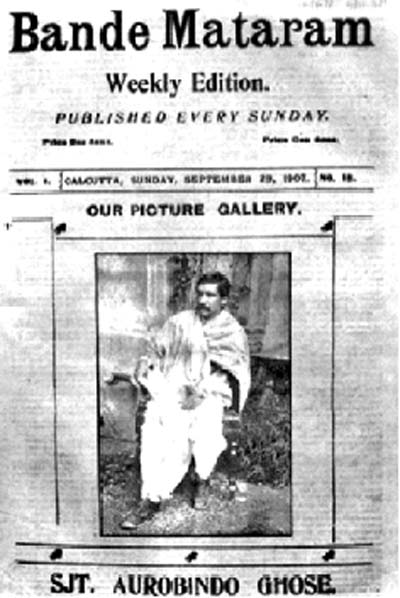

Having equated nation with mother goddess, he goes on to define nationalism as ‘a religion that comes from God—a creed which you [patriot] shall have to live.’ Under the circumstances, the patriot becomes an ‘instrument of God,’ charged with a sacred mission. It is therefore only fair that from Bankim’s Anand Maths to Sri Aurobindo’s conceptualisation of the true patriot, the figure of sanyasi figures prominently in the third school of thought. His method, as Sri Aurobindo outlines in an article in Bande Matram published in 1907, is ‘political Vedantism.’ He developed Swami Vivekanand’s ‘practical Vedanta’ into an elaborate theory better suited for application in the political realm. If Vivekanand described God as the sum total of all humanity, Aurobindo argues that nation itself is the clearest manifestation of that divinity, which he likens to Kali. To serve this nation, he calls upon a new order of sanyasis willing to die for her sake.

It must be underscored that it was this ability to mobilise the profundity of India’s indigenous knowledge resources that endeared him to the masses. This project, as Sri Aurobindo envisioned it, was not only meant to secure political freedom for Bharat; it would have led to the spiritual salvation of the entire world. His identification of mother India with Shakti ignited a social churning whose imprints can be seen all through Bharat’s long attempts at decolonisation—earlier political decolonisation, now cultural decolonisation. It not only served the cause of our freedom struggle, inspiring generations of patriots ready to lay down their lives for the country, but continues to shape new India’s destiny.

(This is the first of the three-part essay on Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy of decolonisation)

Comments