Historical documentation throws up ample evidence of teaching or knowledge sharing in ancient India; it was by and large based on oral traditions. Even in Valmiki Ramayana, the children’s volume compiled by Amar Chitra Katha, there is a sizable portion informing young readers about how earlier students in Bharat did not have textbooks or notebooks. Most of the lessons were passed on orally and pupils had to learn everything by heart so that they would never forget it. Early poets, philosophers and scientists, such as Valmiki, Vyas, Patanjali, Panini and Aryabhatta, all put their work in verse form, which could be memorised easily. In this way, the Vedas, epics, Puranic Kathas and other compositions were preserved in their pure form for thousands of years. Considering that this oral tradition of sharing stories dates back to 5,000 years in the Indic civilisation, we clearly have seen the process grow, evolve and be carried forward with much seriousness in story-telling traditions practised in families as well.

Gods and Goddesses On Big Screen

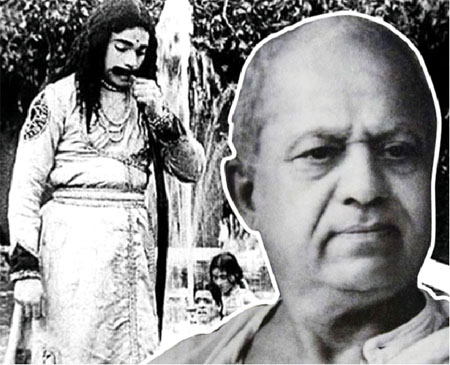

It’s extremely interesting hence how this oral tradition acquired an innovative shape when Dhundiraj Govind Phalke, who is more famously known as Dadasaaheb Phalke in popular culture, launched the motion picture industry in India with the production of the first full-length feature film Raja Harishchandra in 1913. With that milestone finally taking shape because of the visionary’s hard work, determination and dedication to ensure India doesn’t lose out on maximising from this thriving industry concentrated on art and aesthetics, people who till then shared religious and historical sagas, events and incidents they read and heard were able to watch them on screen. The very idea of watching kings, queens, Gods and Goddesses they idolised move like normal people do and not just occupy our imagination or be static was a different experience in itself. What is also noteworthy is Dadasaaheb Phalke’s works (he made over 100 silent feature films) mostly concentrated on stories from the ancient Puranic texts, Ramayana, Mahabharata as well as other famous religious and historical figures. Going by popular demand of the times, these themes were preferred by the masses, which reinforced the fact that people were yet to familiarise themselves with themes outside of this genre in cinema.

Dissemination of Dharma

Considering that art imitates life, cinema before India’s Independence in 1947 largely focused on the importance of inculcating religious and cultural knowledge amongst the viewers. If we were to call cinema an influencing factor in educating people here, the film industry back then primarily delved into the dissemination of dharmic, historical and sanatani knowledge on the whole. Social dramas that harped on the effect the British had on the fabric of society were yet to make their presence felt for reasons galore, one of which could be the censure the makers would face from the imperialist powers. So Phalke and his team had only the option of enthralling the audience with the kind of films they concentrated on. This train of thought was prevalent in theatre as well.

Familiar Territory

The more plausible reason for this particular choice of subjects is depicted beautifully in Paresh Mokashi’s directorial debut, Harishchandrachi Factory, the Marathi biographical film that was selected as India’s official entry to the Academy Awards in the Best Foreign Language category in 2009. Motion pictures back then were an alien concept in Bharat because apart from a few rich and mostly Britishers, no one knew what this medium meant, feels or looks like. A safe option to acclimatise them with moving images would be to offer them a subject they were accustomed to. “As it is, Phalke was making a huge gamble bringing in a new medium. If he would write a story that would be new or experimental, people would find difficulty warming up to the concept as a society, unlike ancient India, had somewhat become a bit closed to new ideas and innovation after years of colonisation. So he decided that Raja Harishchandra and Rani Taramati’s saga would endear them to the concept of a feature film because the characters were popular folklore, too,” explains Mokashi who won the Best Director Award for Harishchandrachi Factory at the Pune International Film Festival that time. He adds, “Art and cinema are also reflective of the time and place they are made in. So, I’d like to believe that when Phalke made his films, society was largely receptive to those themes, when actors dressed up as Ram, Sita, Hanuman, Savitri and such characters from history and mythology, the masses identified with them. If we map the kind of changes eventually film scripts went through over time, filmmakers obviously gauged the pulse of the people and their mindsets before they wrote the stories they did.”

‘Art and cinema are also reflective of the time and place they are made in. So, I’d like to believe that when Phalke made his films, society was largely receptive to those themes, when actors dressed up as Ram, Sita, Hanuman, Savitri and such characters from history and mythology, the masses identified with them’ — Paresh Mokashi, Film Director

Over a period of time, society underwent a change and Mokashi feels that the people too started witnessing the good and the bad around them. Scriptwriters brought elements in. For instance, if you have a Deewar and a Sholay doing well, you also have a successful Jai Santoshi Maa proving that there was a market for various kinds of films as the years went by.

Making Things Relatable

Mokashi’s National Award-winning film on the struggles Dadasaaheb Phalke faced before setting up the feature film industry is rendered with a light, jovial grain, despite its historical nature that usually is viewed as a serious subject. While the director, whose films have always banked on the themes of positivity and hope no matter how tough the going gets, cites artistic liberty, perspective and interpretation, he makes a very pertinent point while explaining why his Phalke always carried the proverbial ‘spring in this step’. Even at a time when tenuous work jeopardises his eyesight for a short while. “Research showed that Phalke never got bogged down by worries or debacles. At every difficult juncture, the thought of initiating the movie industry was so strong in his resourceful mind that he fobbed off all roadblocks with a carefree attitude. Haste haste kathinaiyo ko maat detey thhe Phalkeji. This personality trait of his egged us to maintain a lighthearted tenor in our film”, elaborates Mokashi.

At least, past records have shown that many films that derided our culture, Sanatan Dharma and the Hindu religion without an iota of balance have not really done too well. Maybe, they tend to ride on some trend popular during those times but ultimately it’s the balanced films that always stay timeless

This attitude of Dadasaaheb Phalke was also responsible for the subjects he chose for his works. The Hindu society at large always viewed kings, queens, gods and goddesses in a very serious light. The films, which the visionary realised apart from becoming a prolific money-spinning industry for India in the coming years would also be a medium of influence for people. Hence, it was imperative to convey to them that these were characters that fought against difficulties and dangers without getting too affected by them. This attitude must be inculcated by the masses, too. It was a ray of positivity that Phalke wanted to infuse into the societal fabric clouded by the colonial wrap of the British powers. “Our ancient texts are filled with stories that render important messages in a simple, relatable manner even as they are based on figures we tend to put on very high pedestals. We tried to smudge the lines between chalking of Phalke’s characterisation and the subjects Dadasaaheb chose in this manner so that the maker and the made would seem real and relatable,” says Mokashi.

Tonal Change

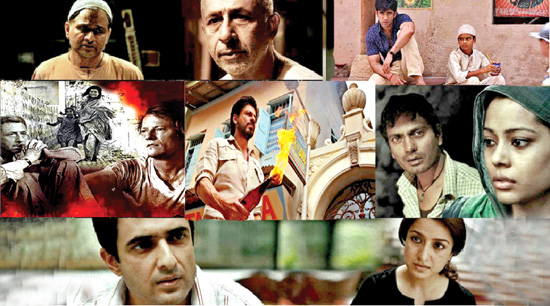

Over a period of time, with the society undergoing several crests and troughs, it cannot be denied that the Hindu society did see the mushrooming of several anti-social elements. Films too reflected that shift in their storylines when social dramas incorporated characters with vices such as malice, greed, selfishness and so on. Humans are prone to have weaknesses, too. This is when filmmakers started including narratives that harped on the bad elements in society as well, moving away from the puranic stories at large. “With growing awareness, the audience too wanted to see movies that would show how the hero battled against the enemy, be it on the battlefield or in his day-to-day life. Social dramas, historical fiction and romances slowly started making their presence felt and people loved them, too. You have to understand that this was a make-believe world that we spent money on so that it gave us a break from daily drudgeries. But, it also depended on the writer and the makers on what mood they would want the film to carry. A spirit of despondence or hope. Highlighting the wrongs was fine I guess till the point they were magnified or normalised because we cannot forget that the roots of India were still good and strong,” avers the director. It is the weaving in of an innate problem-solving ability of the Indian society that Mokashi constantly harps on in the film despite all the problems the characters go through. For instance, in Elizabeth Ekadashi, Mokashi’s second film, a simple but heartwarming tale of siblings trying to save their cycle from being pawned off by their poor mother, the feeling of surviving against all odds and emerging triumphant is the predominant message.

Set against the backdrop of the Ashadhi Ekadashi festival celebrated with much pomp in Pandharpur, the writer, Madhugandha Kulkarni, takes plenty of references from the theories of Newton as she draws a connection between human behaviour and the surroundings around them. The parallels between the temple rituals and the cycle maintenance are apt and sharp, proving how people living in small towns of India nurture a relationship almost with the things they hold dear. This is the primary sentiment that carries the plot forward.

“We could have ended the film on a sad note, with Elizabeth being lost, but then if you look at people in villages and towns of India, there are enough reasons to establish the authenticity of the climax in the film. The ending is not divorced from reality. There are good people around. That is the beauty and bedrock of our country and its centuries-old culture. As a filmmaker, my prerogative is to bring that aspect out. If there are movies where only the dark side is shown, I doubt people would accept that for too long. At least, past records have shown that many films that derided our culture, Sanatan Dharma and the Hindu religion without an iota of balance have not really done too well. Maybe, they tend to ride on some trend popular during those times but ultimately it’s the balanced films that always stay timeless. Cases in point are films made by Hrishikesh Mukherjee and Basu Chatterjee. Because, while pointing out the flaws in society during those times, they also told stories of happiness and hope, feelings that carry us through thick and thin.”

The Double-Edged Sword

Filmmakers, opines Mokashi, have a responsibility towards how to craft narratives in society. However, films also get made as per what gains commercial success so there is a tendency to feed the audience what they are hungry for. Producers, distributors, directors and everyone associated with movies only understand the language of returns as films are a costly proposition. For instance, a film like Harishchandrachi Factory, which had everything running in its favour creatively and intellectually, didn’t do sound business. This hiccup could have deterred Mokashi from making the kind of films he does. But, it’s his perspective of cinema that made him endure the rough tide. “Over a period of time, a host of massy films tend to degrade the taste for art and cinema in the audience. Certain people make films that the audience wants and they would never experiment or try to bring about a shift because of the fear of loss-making ventures. This apprehension also brought about a shift in the mood and subject of films later, from the pre-independence times. Commercial successes determined the types of films made then as the society, more open and aware now, desired to watch them. The snowball effect was that in a way, the flaws in humans and bad things around us got glorified, glamourised and hence, normalised.”

Our religion never forced us to practise it in a certain way yet we all accept it the way we enjoy it. This is the beauty of individuality that Sanatan Dharma allows. If Hindi films fail to understand that it is the most wholesome blend of spirituality and science even as they malign the faith of millions continuously then it is their loss

Maybe, Harishchandrachi Factory, which received immense critical acclaim nationally and internationally, came at a time when the mainstream audience wasn’t prepared for it. Many directors would go on a backfoot after that. But, Mokashi’s intent was always to influence his audience in a positive way. Because of the firm belief that our Sanatan culture, traditions and way of living have the power to do away with the negative and bring forth what’s good in a subtle yet sure fashion. As essentially our Vedic texts are a magical collation of art, science and culture in essence.

The Turning Tide

Fortunately, after seeing the kind of cinema doing well, Mokashi is hopeful that the tide is shifting. Just like the masses warmed up to Phalke’s experiments, the audience now is rejecting the rabid anti-Hindu diatribe of commercial Hindi cinema to welcome and appreciate earnest regional and small-budget works. While not everything is rosy in India, there are films depicting why there is absolutely no reason to crib about life and living in Bharat. Like how Phalke battled difficulties and created history, and his films gave joy as well as direction to his viewers, stories set in the small towns and cities here are bringing us sagas that portray the real India. This thread of relatable content ties today’s new age regional and experimental cinema to the works during Phalke’s time in that way. “I will never say that we make films that do away with the concept of problems that exist in society because that would be unrealistic.”

Like in Elizabeth Ekadashi, what Dnyanesh and Zendu go through is tough, but the film shines because the solution is unique. It reinforces the logic that the Indian brain is capable of solving problems. Good cinema is all about balance and objectivity. Fantasy is all good but the disconnect from life cannot go on for eternity. For instance, if Bollywood’s narrative only focuses on sex, nudity, violence and drugs and their gripe is always against Hindus (the recent being Shamshera’s Shuddh Singh being a Shikha and tilak wearing brutal officer meting out cruelty to the oppressed and the hero shunning Dharma to deliver justice) customs and traditions, there will arrive a moment when that narrative will be rejected. “Our religion never forced us to practise it in a certain way yet we all accept it the way we enjoy it. This is the beauty of individuality that Sanatan Dharma allows. If Hindi films fail to understand that it is the most wholesome blend of spirituality and science even as they malign the faith of millions continuously then it is their loss.” Going by the way big budget films are airing now, it looks like the message is loud and clear. Moreover, from the recent successes of Telugu biggies, as well as works like Panchayat, Jaadugar and Ghar Waapsi, maybe it is a good time for Mokashi’s tales to launch with renewed fervour (apart from the upcoming film releases he is also working on an important docu-series inspired by our Vedic texts). Perhaps, it is his Dadasaaheb Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra moment of 1913.

Sharmi Adhikary is a senior lifestyle journalist and columnist with a yen for exploring interesting concepts in fashion, culture and cinema.

Comments