New Delhi: In these three decades, between 1991 and 2021, India has truly come a long way.

P V Narasimha Rao was also an accidental Prime Minister. He had almost turned into a Sadhu. Sworn in as Prime Minister of India on June 21, 1991, and till December 1992, when the disputed Babri structure was brought down on December 6, Rao got all cooperation from the BJP. And this phase developed the country's economy.

That the BJP has been the country's 'free economy' political party also helped in the overall endeavor.

The post-economic reforms era after 1991 is certainly, and directly related to human development and the nation's development. We have amazing stories of ordinary Indians making extraordinary opportunities provided by the liberalization and open market policies.

It was only during the Vajpayee regime of 1999 and beyond that middle-class Indian boys and girls dreamed about having their own 'houses and flats' in highly demanding and cash-rich cosmopolitan cities of Delhi and Mumbai.

But all of it did not come easily. Some Congress leaders were highly skeptical of dismantling the Nehruvian structure that in effect promoted License Raj.

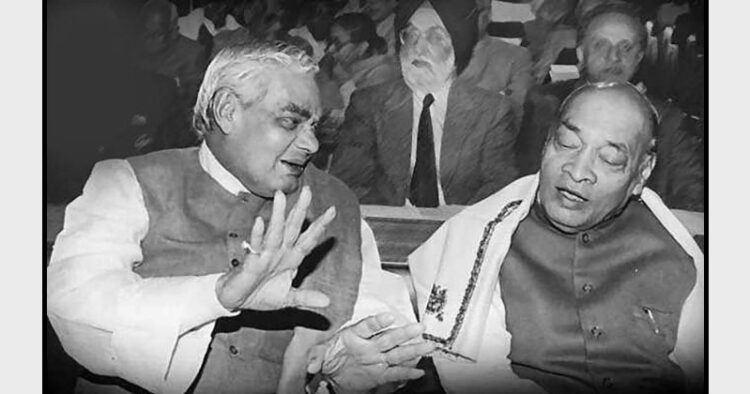

Credit should go to P V Narasimha Rao and also to the then Cabinet Secretary, Naresh Chandra. And also the Opposition leaders of the time – the likes of L K Advani, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Rao's immediate predecessor Chandrashekhar.

Rao took over as the Prime Minister on June 21, 1991, but a day ahead (June 20); as PM-designate, he held a crucial round of meeting with Naresh Chandra and got the briefing of the country's dismal economic condition. Rao then turned to his Finance Minister, Manmohan Singh, as well as other opposition figures, such as LK Advani, for help in 'understanding' the difficult situation. Initially, Rao lacked a majority in the Lok Sabha, and in a show of force, the BJP staged a walkout during voting to aid Congress in achieving the required numbers.

A week after taking charge as PM, Narasimha Rao met the opposition leaders separately and briefed others including Chandrashekhar, Yashwant Sinha (who was outgoing FM), V P Singh, Advani, Harkishan Singh Surjeet, and Madhu Dandavate, also a former Finance Minister. The IMF conditionalities were issues, and some opposition leaders had their reservations. Finally, on July 4, 1992, IMF chief Michel Camdessus expressed 'satisfaction over the Indian government's implementation of the conditionalities.

Looking back, the Indian economy and socio-economic conditions in the 1950s and the 1969s passed through an era of shortages. In the 1970s, one needed a letter from an elected Member of Parliament if one had the desire to buy an HMT watch out of turn. Even in the eighties, as a young man growing in the Assam Rifles camps in Nagaland, I witnessed how our relatives and acquaintances would make a beeline to my father for HMT watches from CSD canteens.

The same phenomenon applied to the gas connection and landline telephones even till the late 1990s. Visits to banks were a nightmare and daylong hassles.

When I shifted to Delhi in 1998, a dear friend and an esteemed colleague of mine H C Vanlalruata helped many senior New Delhi-based journalists (at the PTI headquarters) to get a landline telephone connection at their residences. This was because he knew one Telecom Minister and some of us!

We all knew that the era of a regulated economy would be replaced slowly. And of course one feature of that ‘regulated economy’ was that those who may grow at the discretion and a price for the state (government), also ensured that others in competition would not grow.

By 1991, when the reforms were implemented, India had “unleashed its energy,” as the late Arun Jaitley put it.

The Telecom revolution was truly revolutionary. Youngsters of my daughter's generation would not know the beelines made in front of STD booths for late-night calls after 11 pm because the charges would be minimum.

In retrospect, the system of permit and license raj stifled individual aspirations, ambition, and achievement. It practically tied down India.

The reforms brought by P V Narasimha Rao assisted by his Finance Minister, Manmohan Singh, actually unleashed new entrepreneurs. Many years later, it aptly cited that the 1991 liberalization gave a businessman named Anil Agarwal the courage and platform to transform his business from a metal-scrap dealership into a mining-and-metals conglomerate.

The competition brought prices down, and there was a plurality of choice. There came in better services and qualities and also better pricing.

This was also a path-breaking era wherein the middle class started thinking big. No longer had people thought to be a business honcho and one needed the right heritage.

We may like or dislike someone. But people like N R Narayana Murthy have proved that with the right mix of hard work, planning, and use of talent and skills, one could build an empire from scratch with no ancestral business behind.

This marked the democratization of the Indian business scene. Persons and a small group of individuals arrived, developing a taste for risk and eventually delivering initiatives that boomed.

It also opened opportunities for others who got employment and also 'opportunities' to achieve bigger milestones at their levels.

Thus, in the subsequent period between 1991 and 2001 alone, we found India could produce 2 lakh millionaires and hundreds of billionaires. Notably, it took more than a century in the United States to generate such numbers.

Importantly, young Indians have emerged as "drivers of the nation's destiny," a break from previous tendencies in which there were many reasons and roadblocks to young people undertaking a variety of great things. The 'seniority' counted more, even if there was laziness and non-performance.

Look at India of the late 1980s and early 1990s – when TV serials like 'Chunauti' and 'Udaan' (on Doordarshan) and 'Campus' and 'Banegi Apni Baat' on Zee TV made waves. By the way, TV business tycoon Subhash Chandra is also a creation of that post-liberalization policy era.

Comments