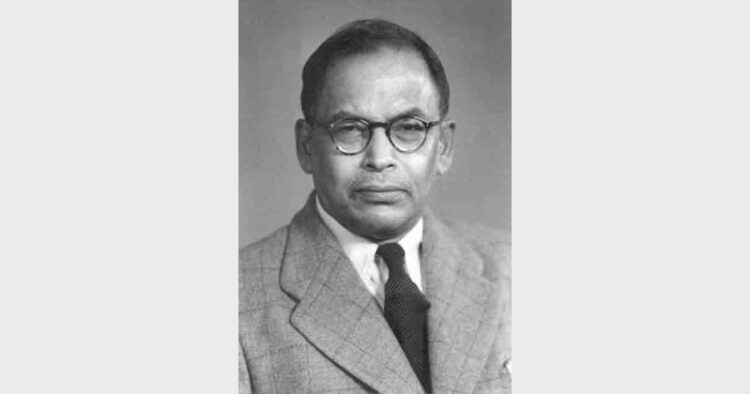

-Agrah Pandit

Indian polymath Meghnad Saha (1893-1956) was the first to propose that a star’s spectrum indicated its temperature and chemical-physical composition. Thanks to Saha, man could finally understand what stars really were—fiery balls of hydrogen—for the very first time. Much of the modern astrophysics and astrochemistry has been termed as a mere footnote to Meghnad Saha’s works. He advocated progress in science and technology as an instrument to facilitating the process of decolonization. He was instrumental in the founding of Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics and journal Science and Culture, besides many more such initiatives. He was responsible for creating India’s national calendar, Saka calendar, which is arguably the most scientifically accurate calendar in the world. An outspoken critique of Nehruvian policies and a supporter of large-scale industrialization, he would find himself cornered by the establishment, prompting him to contest Loksabha elections of 1952 in order to set right nation’s priorities. Organiser remembers this karmayogi on his 127th birth anniversary on 6th October.

A Pioneer of Astrophysics and Astrochemistry

All stars produce a characteristic spectrum—a barcode-like pattern of thin, black lines that appear when starlight filters through a prism. Before Saha’s discovery, stars were classified into Linnaeus-like taxonomies based on similar spectra. However, it had not yet been understood what caused a star’s characteristic spectrum.

Meghnad Saha explained it with his thermal ionization equilibrium. Thermal ionization is the stripping away of electrons as atoms heat up. When electrons within atoms absorb light of specific frequencies, it creates the dark bands in stellar spectra. Saha determined that as temperatures rise, more and more electrons strip out of atoms, and the location and number of the dark bands change. In simpler words, different temperatures lead to different patterns of bands. So, when astronomers were sorting stars into different groups by spectrum, they were actually sorting them by temperature. Saha thus combined chemistry with physics in answering the old riddle by equations of thermal ionization (aka Saha Equation).

Meghnad Saha’s equations would further help answer other riddle of astrophysics like the precise temperatures of stars, chemical and physical conditions of stars. By observing spectrum of a star, one can deduce, using Saha Equation, its temperature and ionisation state of various elements making the star. Owing to Saha’s towering contributions, astronomy became a genuine, predictive science. Norwegian astrophysicist Svein Rosseland, in his well-known Theoretical Astrophysics remarks thus:

“Although Bohr must thus be considered the pioneer in the field [of atomic theory], it was the Indian physicist Meghnad Saha who (1920) first attempted to develop a consistent theory of the spectral sequence of the stars from the point of view of atomic theory…The impetus given to astrophysics by Saha’s work can scarcely be overestimated, as nearly all later progress in this field has been influenced by it and much of the subsequent work has the character of refinements of Saha’s ideas.”

Saha also invented an instrument to measure the weight and pressure of solar rays. Later, he would discover phenomena of Selective Radiation Pressure though he was deprived of its credit. He has been called Darwin of Astronomy.

Education and Industry

Meghnad Saha was of opinion that the rich men must come forward to patronize science and research in India. “If poverty is to be successfully combated it can be done only by the greater diffusion of scientific knowledge, and by the adoption of scientific methods to agriculture and industry. And this cannot be done solely by the government. India’s rich men must scale the moral height of Andrew Carnegie who held that “To die rich is to die dishonored”, and we may add that to leave millions for your children or successors, which they have not earned themselves is not only to spoil their future but is in most cases, actually to push them along the road to perdition!”

In 1949 Saha founded the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta, with the patronage of J. R. D. Tata. He was instrumental in setting up Physics Department in Allahabad University and dozens other institutions of learning. First ever nuclear physics syllabus in M.Sc. was designed by him as well as country’s first cyclotron. He wanted the government to set up a hydraulic research laboratories for the study of problems of river training, flood, irrigation, navigation and hydraulic power development as well as river commission for major river systems.

As a parliamentarian, he advocated implementation of many reforms in higher education, as proposed by UGC: the university education should be on the concurrent list, not a state subject; the President of the Republic should be a visitor to all the universities of India; it should be the concern of the Central Government to provide ample resources for the development of universities; the money so provided should be spent through an autonomous University Grants Commission, which should be properly constituted.

Indian National Calendar

At the time of independence, India had numerous calendars. Although the Gregorian calendar introduced by the British retained its pre-eminence, the majority of the country’s Sanatana Dharmis (Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains) followed a Hindu calendar (panchang) for observing their festivals while Muslims followed Hijri calendar. To bring uniformity and accuracy to time-reckoning, a calendar reform committee was constituted by CSIR under Meghnad Saha in 1952.

Traditional panchangs were based on rules laid out in the Surya Siddhanta, an astronomical treatise written around 500 AD. The length of a year, as measured by the Surya Siddhanta, was 365.258756 days. However, Saha observed that the actual length of a year was 365.242196 days. This had led to an error accumulating to 24 days over last 1450 years, since Surya Siddhanta. Islamic (Hijri) calendar was much more erroneous. Gregorian calendar fared no better than traditional Indian panchangs when it came to accuracy.

Meghnad Saha, who Believed that astronomy is the first of all sciences, and the oldest of astronomical problem was the calendar, was just cut for the job. Saha-led committee developed world’s most scientifically accurate, all-India National Calendar: Saka calendar. The Saka calendar marks its new year on the Vernal Equinox. The months begin with Chaitra and end with Phalguna, each 30 or 31 days long. It uses the Saka era to count years. The Government of India officially started using the Indian National Calendar on 1 Chaitra 1897 (i.e. 22 March 1957), along with scientifically inaccurate yet widespread Gergorian calendar. Saha argued, “National Calendar will prove not only a boon but also a great unifying factor in our country.”

A Nationalist

Meghnad Saha was a nationalist to the core. As a schoolgoer, a young Saha had participated in boycott protests when Bengal was partitioned into Muslim-majority East Bengal (which included his hometown) and Hindu-majority West Bengal. He was also associated with revolutionary groups like Anushilan Samiti. Germany had shipped arms by sea during World War I for India’s revolutionary efforts. Saha and Jadu Gopal Mukherjee were assigned the task of picking up the weapons from the ship carrying it. However, the ship was intercepted by the British and the mission failed.

Later, he realised that progress in science and technology and revival of ancient India’s intellectual past were equally important in a struggle for India’s decolonisation. His mentor at Presidency College, Prafulla Chandra Ray, had authored A History of Hindu Chemistry from the Earliest Times to the Middle of the Sixteenth Century A. D. Another mentor, the celebrated J. C. Bose, in his 1902 book Response in the Living and Non-Living, linked nationalism and science and dedicated the work “to my countrymen, who will claim the intellectual heritage of their ancestors.”

Meghnad Saha founded journal Science and Culture, modelled after the prestigious British science journal Nature. The purpose was to highlight the social function of science and to combat ignorance by disseminating science to the masses in non-technical terms. Saha thus sought to fight colonialism in intellectual sphere.

Meghnad Saha personally organised the Bengal Relief Committee to carry out the relief and rehabilitation of millions of refugees who were forced to flee their homes following partition in 1947 when he felt that government’s rehabilitation and relief work was woefully inadequate.

A Lone Warrior

Meghnad Saha’s views on river management, refugee crisis, state of higher education, railway reconstruction, India’s need for power development, irrigation research, etc. betrayed a distinct socio-cultural awareness not shared by many of his colleagues. He was a man of and from masses. He found himself cornered among his own scientific fraternity as well as political establishment due to his radical reformist views. His views were often at loggerheads with those of Nehru and Gandhi. Nehru was too elitist while Gandhi too medieval, felt Saha. Saha wrote to Nehru in 1945:

“I believe the time has come when the Congress should formally announce their programme of work in case they get power. Its present programme is too much tied up with old world ideologies—like spinning wheel and homespun, division of power on medieval basis etc. etc. We should give to the country new slogans based on the idea of working up ‘a decent living for India’s masses’ based on the fullest use of science, development of power resources, chemical, mineral and agricultural industries, collective and multipurpose use of land and water, rebuilding of society on the new basis of work.”

Meghnad Saha felt that Nehru was in a hurry to establish a scientific and industrial base, though Saha himself was advocate of large-scale industrialisation and scientific development. The friction in Nehru’s relationship with Saha was in sharp contrast to the congeniality that existed between Nehru and other scientists like Homi Bhabha, Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar, and C.V. Raman. Despite Saha’s opposition to the establishment of an Atomic Energy Commission on the ground that India at that point did not have the necessary industrial base or the required manpower, the Government of India however went along with Homi Bhaba’s proposal.

An alienated and cornered Meghnad Saha entered first Loksabha of 1952 so as to fight for the correction of nation’s priorities in parliament. Like a constructive Opposition, he praised government where he felt policies are in sync with reality, for instance, he wholeheartedly supported the govt. on Damodar valley project. But he let his mind known in case of what he felt as policy distortion. Saha’s questions were oftentimes difficult to face because his arguments were based on solid facts and findings. For this, he was sought to be silenced—often by recourse to rhetoric and casuistry rather than debate and discussion. On multiple occasions, Nehru, the ever-brilliant orator as he was, termed Saha as ‘used to be a great scientist’ or ‘one who drifted from the fields of science and has found no foothold elsewhere yet’, ‘fallen into such evil ways of thinking’, etc. Max Weber described two kinds of politicians: who who lives for it and one who lives off it. He was of third kind. He entered politics out of reluctance because he could not be a mute spectator of what he felt as policy drama.

(From left to right: standing – S. Datta,S. N. Bose, D. M. Bose, N. R. Sen,

J. N. Mukherjee and N. C. Nag. Sitting – M. N. Saha, AcharyaJagdish Chandra Bose and J. C. Ghosh)

J. N. Mukherjee and N. C. Nag. Sitting – M. N. Saha, AcharyaJagdish Chandra Bose and J. C. Ghosh)

Saha and Nobel

Meghnad Saha was nominated for Noble in 1930, 1937, 1939, 1940, 1651 and 1955. While nominating Saha in 1940, A H Compton notes that “Not only has this work been fundamental to much of the recent development in Astrophysics, but it has also formed the basis of recent physical studies of the thermodynamics of high temperature ionization.” However, astrophysics had become synonymous with astronomy by 1930s. Since Alfred Nobel clearly had not intended astronomy to be eligible for his Prizes, astrophysics no longer could be eligible for Nobel in Physics. One more reason is that when he sent his theory of selective radiation pressure to Astrophysical

Journal, the journal asked Saha to bear some of the printing costs. He himself financially strained, he published it instead in low-visibility Journal of the Department of Science at Calcutta University. Predictably, some Westerner later appropriated credit for it.

Meghnad Saha’s is a story of being cornered—beginning with the disabilities associated with being born in a lower caste and poor family, then to Nobel prize committee to politics to scientific fraternity—yet remaining indomitable. He was a lone warrior. And as they say, alone warrior is destroyed but not defeated. While repeatedly being cornered and attacked personally in parliament, he roared back once, “I may add that I have done very little in science, but my name would be remembered for some hundreds of years while some politicians here will go to unregretted oblivion in a few years.” History is a living proof to it: Encyclopaedia Britannica terms his thermal ionization equation as “fundamental in all work on stellar atmospheres”. Writing for Encyclopaedia Britannica, Arthur Stanley Eddington included Saha’s equation amongst Top Ten most outstanding discoveries made in astronomy and astrophysics since the discovery of telescope, in 1608, by Galileo.

Comments