Kingshuk Nag’s portrayal of the RSS Supremo Shri Mohan Bhagwat in his book Mohan Bhagwat: Influencer-In-Charge, comes off as a facile attempt at understanding the humongous personality of the leader. An attempt that could have brought him rich dividends is marred by shallow writing based on blatant rumours, hearsay, and partisan news websites. Thanks! No Thanks, Mr. Nag!

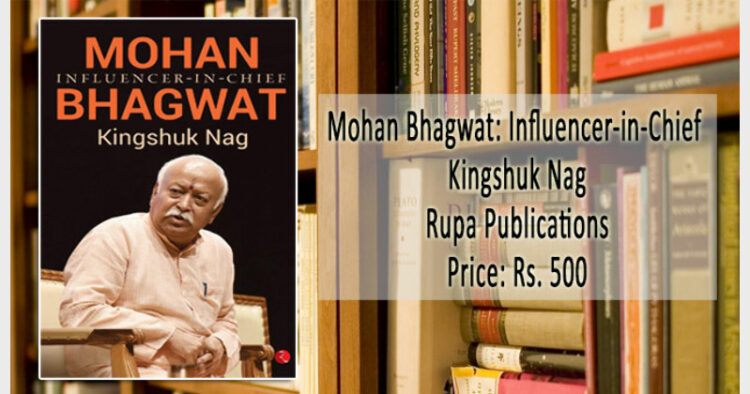

About Book : Kingshuk Nag, Mohan Bhagwat: Influencer-in-Chief (Rupa Publications), pp 240, Price: Rs. 500

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is the flavour of the seasons on both sides of the political and ideological divide. People can’t have enough of it as there is not much else available in public space. What you find is mostly unbridled criticism or rank abuse. This in the face of an alleged atmosphere of perceived ‘intolerance’ thanks to the BJP Government that appears to have a strong stamp of RSS written all over it!

Now a days, many people jump on the RSS bandwagon, hoping for a quicker climb to political power and fame, wrongly believing that it is the right door, while some people attempt to ‘write’ the story about RSS in the hope of attaining instant fame. And Kingshuk Nag has done exactly that. A book about RSS Sarsanghchalak, as people like to call Dr Mohan Bhagwat.

However, we can see from his Preface itself that he is prone to kite-flying which can prove very risky to his credibility, especially in the case of RSS. To cover up his folly, he uses rumours circulating in the media as supporting ‘evidence’. For example, he quotes Zee News to claim, “He (Pranab Mukherjee) may be the most preferred candidate for the position of prime minister after Narendra Modi in case the BJP fails to get a majority on its own!” (Preface, page xvi). He routinely resorts to similar rumour-mongering (many times without reference or from leftist news portals) beginning with the ‘Introduction’ of the book. By the time you manage to wade through the Preface and Introduction with enormous patience, you know you are just wasting your time reading this not so serious writer.

In this book, Nag talks approvingly of “Bhagwat reaching out actively to Muslims and Dalits” overlooking the fact that this conscious outreach began from the times of Shri Sudarshan ji’s and Shri Balasaheb Deoras’s themselves. Dr Mohan Bhagwat has surely taken that momentum forward. The writer hasn’t taken the trouble to find out that much earlier Guruji was the person who brought all the Hindu saints during the thousand years of history on a single platform of Vishwa Hindu Parishad to persuade all the saints and gurus to pronounce that no Hindus fallen (or untouchable) and that all Hindus are children of same mother (Earth). But, he does quote Shri Guruji from ‘We Our Nationhood Defined’ that was written before he took responsibility as head of RSS and had dismissed as ‘outdated and not relevant anymore’ but doesn’t take trouble to project his moves to reform Hindu society.

Lack of research leads him to make outrageous claim that “there was no question of RSS participating in the Quit India Movement.” (page 8) despite sufficient evidence produced by various RSS publications. It is painful to see how he dismissively says, “Mookerjee (founder of Bharatiya Jan Sangh) died under mysterious circumstances… he had been arrested while entering Kashmir ‘illegally’. There is no mention of his historic agitation for complete integration of J&K and protest against “two constitutions, two flags” – Article 370 and the Sheikh Abdullah-Nehru agreement! He then goes on to treat assassination of Deendayal Upadhyay lightly stating, “He (Deendayal Upadhyay) was thrown out of a moving train just 20 days after taking charge.”(page 12).

Nag’s penchant for making rumours sound as if he has ‘inside’ information that makes him claim that Yogi Adityanath is the successor for RSS bosses in 2024! He uses leftist news portals, like scroll.in for many of his conjectures which actually punctures his standing as a serious writer.

I trust that he began with honourable intentions. He may have met with some RSS leaders, including very senior netas in the organisation and did some research. However, his book comes out quite shallow. It lacks the depth that a subject like RSS Chief or RSS itself would require, considering that the title of the book “Mohan Bhagwat – Influencer-In-Chief” sounds quite catchy with a ‘buy me, please’ kind of appeal. The very fact that Dr Bhagwat did not grant an interview to Mr Nag could have been an interesting point of analysis of his reclusive personality, as a leader who shuns publicity. But, he seems to have missed this point.

The redeeming feature of his book are last two chapters that touch upon unknown facets of larger social movement that is the outcome of decades of RSS work – 93 years to be precise. A few personal anecdotes about Dr. Mohan Bhagwat are interesting for outsiders and throw light on his personality. They show the humane, light, easy-going nature of Dr Bhagwat. The ‘Epilogue: Phir Ek Baar Modi Sarkar? is a skimming of political scenario and the entire argument that the author builds in the book ends in a whimper here.

RSS is not an easy to understand organisation because it doesn’t fit into a your typical social organisational framework to which social scientists are attuned. Hence, his critique, though well intentioned, comes out poorly. One expected lesser errors in this book on basic facts while Chapter 2: Pushing the BJP to Power, seems like an afterthought on insistence of the editors of the publisher as it sounds very superficial, done with quick few, wayward brush strokes. This could have been as interesting as the chapter 10 and 11.

His narrative on the re-election of Shri Bhaiyyaji Joshi as the Sarkaryavaah for the fourth term using ‘news outlets’ and claiming that “news about his ill-health was ‘planted’ news” (page 59) is rather amusing, to say the least. Everyone who is in the know, knew that Bhaiyyaji Joshi had knee problem and that he was going for knee replacement. This kind of surgery is not really treated as ill health. Rumours were all media-generated, not RSS-generated.

Every RSS Sarsanghchalak has travelled continuously since 1925. In fact, Guruji had once said that train compartment was his home (including second or third class compartments). He had travelled in most challenging times. It is a tradition. So, to claim that Dr. Bhagwat is doing something more or different is an avoidable hype. He claims, “Ever since the BJP came to power in 2014, the sarsanghchalak had been working hard and touring the country to unite the Hindu community. (page 66) No doubt the current Sarsanghchalak is travelling even harder than the previous heads of the organisation. Actually, all the prachaaraks are also travelling very frequently. If one were to count their miles, it could have created a world record for RSS’s office bearers.

In one of the major bloomers, Mr Nag talks of a “programme to inculcate nationalism among Arunachalees, the RSS set up a Sarhad-ko-Salaam group.” (page 89) The fact is ‘Sarhad ko Salaam,’ a nationwide path-breaking programme, was organised by an associate organisation of RSS – Forum for Integrated National Security – FINS in 2012 for the youth. Being a patriotic venture, RSS gave its full support. This programme was across length and breadth of India where youth upto age of 25 were chosen to visit borders from North to South, from West to East and to meet the locals and security forces there.

Nag talks of RSS chief Dr Mohan Bhagwat taking up Kashmir issue actively with BJP coming to power in 2014. If he had studied the RSS resolutions, he would have noted that RSS has passed 29 resolutions on Kashmir in its Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha (ABPS) since 1950 and its swayamsevaks worked actively to fight separatist forces since 1947-48. It formed special study groups twice to get a better understanding of Jammu and Kashmir problems in all their dimensions.

Kingshuk Nag makes a very perceptive observation on page 144. He notes, “ABVP is now countered not by Left organisations but bodies which owe allegiance to Ambedkar and the like.” He could have added that these Amebdkarite bodies are actually a cover for Maoist movement to spread foment unrest in the society and exploit its fault-lines, in the garb of ‘Cultural Studies’ promoted by the Neo-Left.

The author makes a surprising observation that earlier RSS did not maintain statistics on the number of swayamsevaks, only on number of shakhas. (page 148). This critic who has been part of RSS from childhood can assert that the attendance formed the basic data point for any RSS shakha mukhya-shikshak and karyavah’s reporting and this information would be compiled right upto state level to be presented in summarised form to the designated authority at the centre.

RSS Sarsanghchalak is the face of the organisation for the outside world. He is guide and philosopher of the organisation setting out broad contours of policies but no policy in RSS is accepted without wide ranging discussions among the seniors, the top most leadership. Consensus is the key. The author has failed to highlight this organisational strength of RSS. In his urge to justify the title of the book, long-held beliefs and strong policy issues for decades are ascribed to Dr. Mohan Bhagwat. For the author RSS, the organisation and Dr. Bhagwat, the Sarsanghchaalak are interchangeable terms when he describes variouspolicy initiatives. No doubt, RSS swayamsevaks look up to the Sarsanghchalak with huge respect as he is the leader of the organisation, but when the founder Dr. Hedgewar chose ‘Bhagwa dhwaj’ or flag (that the author keeps referring to it as Bhagwa jhanda) as the Guru of the organisation, his prime objective was to create an organisation that is ‘vyakti nirapeksha’ that is not dependent on any one individual.

Mr Nag’s urge to equate the RSS chief to the organisation goes against the very ethos of the RSS. That he chose to do this in spite of meeting very senior members of RSS is surprising. Another interesting point is that a Sarsanghchalaks of RSS can be questioned, for his pronouncements in the RSS meetings. This democratic strength of RSS doesn’t come out strongly at all in this book. It comes out fleetingly when the author traces the history of ‘half pant’ to ‘full pant’ but not really underlined by the author.

The book’s title may appear to promise an ‘insider peak’ into the working of the current RSS chief as the influencer in chief for the national politics, but endeavour seems to be a damp squib. The concluding chapter has been written so poorly that even a magazine article would have fared better when speaking of the forthcoming 2019 elections.

Since most people tend to ‘judge a book by its cover’, it may be a commercially successful venture for Mr Nag, due to the controversial nature of the topic it has chosen to deal with, production quality and a powerful cover design. But readers will be disappointed with lack of depth in the book. Kingshuk Nag may have acknowledged some of the key persons in the RSS like Dr Manmohan Vaidya and MG Vaidya in helping him understand RSS, but the actual outcome of his discussions with them is quite disappointing, to say the least. He has missed a good opportunity to analyse RSS vision of India and its impact on Indian politics.

(The writer is author of the book RSS 3600)

Comments