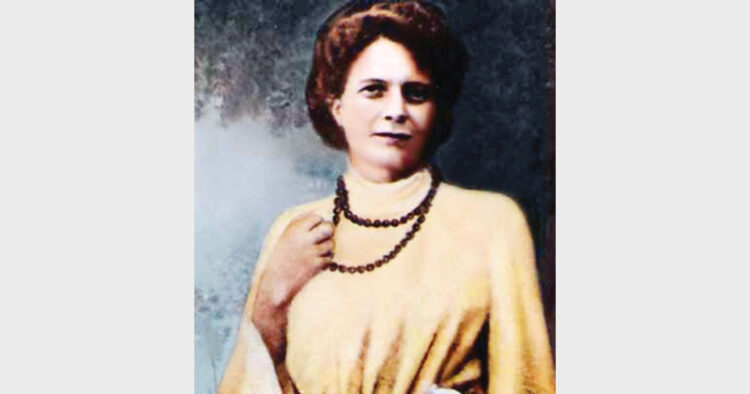

Born in Ireland, Sister Nivedita dedicated her life at the feet of his master in service of Bharat. The writer analyses her contributions to the Indian womanhood and other various spheres

Ranga Hari

Sister Nivedita was the beloved disciple of Swami Vivekananda, who used to call her his

“daughter.” She was just five years younger than Swami Vivekananda. And like her master’s, her life also was very short. Swamiji attained Samadhi even before he completed forty years. And the disciple attained Samadhi when she was just forty-four years old. Swamiji’s public life lasted almost a decade after he got the epithet Vivekananda. And the disciple’s public life lasted almost fourteen years, since she reached Bharat. The disciple’s public life started when she was twenty-five years old and it was during this period that she started her own school in Wimbledon, introducing certain novel concepts. But Swamiji’s public life started when he was thirty years old.

Margret becomes Nivedita

It was in England where Margret Noble met Swami Vivekananda for the first time. And soon after this, she started calling him ‘her Master.’ During those days, once he told her: “I have plans for the women of my country in which you, I think, could be of great help to me.” And that proved to be the turning point that paved the way for her mental

transformation. Months passed by, and the master who had returned to Bharat wrote to her on July 29, 1897: “Let me tell you frankly that you have a great future in the work for India. What was wanted was not a man, but a woman- a real lioness- to work for the Indians, women specially. India cannot yet

produce great women; she must borrow them from other nations. Your

education, sincerity, purity, immense love, determination and, above all, the Celtic blood make you just the woman wanted.”

The disciple reached Bharat at the same age her master had reached America. This was a period in which a Hindu, who opted out of his

mother-faith, never used to return to her fold. A period in which it was believed that if one crossed the sea, Sanatana Dharma would get drowned and be lost forever. And it was in such a situation that the omniscient Lion of Vedanta, “imported” a disciple from the West. “Would the

orthodox Bharat accept her?” was the Guru’s doubt. He presented her before an

ordinary-looking revered Sharadamani Devi. The mother called her “daughter” with utmost affection. Then the Guru felt assured that the whole of Bharat had accepted her. On that auspicious moment, the mother’s small room turned into the labour room of the resurgent Bharat.

On the 57th day of her arrival in Bharat, the Guru gave the disciple Brahmacharya Deeksha (oath of

celibacy). Offering her as libation at the sacred feet of this Dharmabhumi, he

transformed her into Nivedita. And she became the Bhagini (sister) of the entire Bharat. Then, along with the disciple and some other companions of his, the Guru went on a pilgrimage to the Amarnath shrine. In fact, this was in accordance with the tradition of the “Gurukula”

system of yore. It was obligatory for Brahmacharis to undertake a long

journey after the culmination of their study, to acquire worldly knowledge through observation and direct

experience, and it was Vivekananda’s desire that his disciple should acquire this knowledge. During the pilgrimage he made his disciple acquainted with the nationalistic standpoint and viewpoint. To be precise, it was Nivedita’s Indianisation that was taking place. In other words, it was during this journey that Margret Noble truly became Nivedita, to which her own words bear testimony: He said, ‘An educational effort must begin at the standpoint of the learner…If you want to know what a ship is like, the ship has to be specified as it is- its length, breadth, shape and material. And to understand a nation, we must do the same. India is idolatrous. You must help her as she is. Those who have left her do nothing for her.”’ (1: 206)

Swimming against the Tide

After the pilgrimage, they returned to Calcutta. And in the 8th month of her arrival in Bharat, in the august presence of the Divine Mother Sharadamani, Nivedita started a girls’ school. It was really an act of swimming against the tide. The mental attitude of the people at large was far behind that of Swamiji. But, for the Brahmacharini, who was fully immersed in the atmosphere, it was not quite unexpected, and, like the

goddess of patience, she continued to move forward slowly, with all patience. Swamiji had given her full freedom and never used to interfere with the running of the school, knowing well the aptitude of Western women for freedom. At the same time, he used to watch even the minute developments intently. Some times he felt that the founder of the school was indulging in more public contact than was required. But he kept that feeling to himself. The mind of the person requiring correction is equally important as of the one who is out to correct it.

Swamiji waited for the opportune moment, and he got the opportunity

during his second foreign voyage. He had ample time to talk to his disciple during the ship journey and there was absolutely no pressure of any worldly concerns. While talking about her future work for women, he told her with

definitiveness: “You must give up all visiting, and live in strict seclusion. You have to set yourself to Hinduise your thoughts, your needs, your conceptions, and your habits. Your life, internal and external, has to become all that

an orthodox Hindu Brahmin Bramacharini’s ought to be. The method will come to you, if you desire it sufficiently. But you have to forget your own past, and cause it to be forgotten. You have to lose even its memory.” (1: 206)

The disciple assimilated the advice without any reservation, and the lecture she delivered on November 30, 1901, at the London Foreign Press Association, at Adelphi in London, reported on December 1, 1901, read: “Miss Margret Noble alias Sister Nivedita, spent

a-year-and-a-half to study the lives of Indian women. She was not merely in sympathy with what was noblest and best in Hinduism, she was in sympathy with Hinduism as a whole, and took it with its faults and with its virtues. She would, therefore, offer no criticism of Hinduism. She thought that, taken it all in all, it was about the most magnificent system of civilisation and supplied the finest educational instrument the world had ever seen…Everything the Hindu touched became ethical. Of all beautiful things in this world there was probably nothing as beautiful as the life of a Hindu household. The great ideal of Indian womanhood was not romance but renunciation. Without impairing this ideal she was anxious to give the Hindu women modern practicality.” (2: 494).

Nivedita’s this trip abroad was unique in the literal sense. In millennia old Indian history this was the maiden venturing out by a woman missionary. The world acknowledged her as the one who was dedicated to Bharat. And her actions and traits were fully conforming to it. Hers was the authoritative voice that spoke for Bharat. She firmly believed it to be an essential duty, and not an act of charity, of the civilised humanity to support the work aimed at the uplift of Indian women.

A Woman with a Mission

She, who since then, returned to Bharat, enlarged her area of activity. She also could get recognition at the national level. At the same time, she also became a suspect in the eyes of the British rulers. She strongly believed that education or uplift of women would be meaningless without the national feeling. She used to present the views she had imbibed from her

master before the people without mincing her words. And none of the reputed leaders of the time had anything to say against what she said. She said: “When the women see themselves in their true place, as related to soil on which they live, as related to the past out of which they have sprung; when they become aware of the needs of their own people, on the actual colossal scale of those needs; when the mother-heart has once awakened in them to beat for the land and people, instead of family, village and homestead alone, and when the mind is set to explore facts in the service of that heart- then and then alone shall the future of Indian womanhood dawn upon the race in its actual greatness; then shall a worthy education be realised; and then shall the true

national ideal stand revealed.” (2: 76-77)

“…It is clear that the objective of the old education of Indian women lay in character, the new cannot aim lower. The distinctive element, therefore, in their future training cannot be reading and writing- though these will undoubtedly grow more common – but the power to grasp clearly and with enthusiasm the ideas of nationality, national interests, and the responsibility of the individual to race and country…” (2: 76).

When English system of

education was introduced in Bharat, men and women everywhere, although not in large numbers, came forward to work in that field. Christian missionaries, with an aim to proselytise people, were in the forefront. And for Pandit Ramabai, a Christian lady who was under their influence, it was a practice to condemn everything Bharatiya. In her opinion, education was a social service activity that helped others to gather information. And it was precisely this attitude that was criticised by Swami Vivekananda in another context, as the “rucksack of the arrogant.” Nivedita, to whom this

viewpoint came down from her master, strongly believed that culture, Dharma and the nation have an umbilical

connection. And she also introduced this viewpoint before the great educationists of that period, including Rabindranath Tagore, who was highly influenced by her. Now let us take a look at the clarity of her thoughts: “The great end and aim of all educational efforts then lies in

rendering the individual efficient as an atom in his community and that

community efficient as an atom in humanity. To do this, a certain care and forethought are necessary. For it is in his own community that the individual is to inhere. Here we come on the crime of those who educate an Indian girl to be an ornament of English or French society… By a false education, she has been made critical of her own people and their

institutions, without herself fulfilling the ideal of any other. It is not by teaching a Bengali girl French, or the piano, but by enabling her to think about India, that we really educate her, and make her of her own with whom the world’s greatest minds are proud to be associated” (5:25).

“A woman in whom great

compassion is awakened; a woman who understands the national history, a woman who has made some of the great Tirthas and has a notion of what her country looks like, is much more truly and deeply educated than one who has merely read much… If Sita and Savitri are ever to be born of Indian mothers, we must create new types for them,

suited to the requirement of the modern age. Gandhari must live again, with new names to think of, but all the faith and courage, steadfastness and sacrifice. Damayanti must return, and Draupadi, the fit wife for Yudhishthira, king of

justice. Awake! Awake! The greatness of Indian womanhood must be the cry of Indian men.” (5:222-223)

“Humanity is only complete in the two-fold organ, the feminine mind

united with the masculine, and neither alone. It is difficult to see how the new function of the intellect can arise, without introducing for girls the old ideal of the student-life, which has been so many centuries in force for boys. This is one of the noblest because most austere of the world’s ideals. But it must necessarily postpone the age of marriage. It has been well said that if an uneducated woman can solve problems of nursing and housekeeping, an educated woman should solve them so much the better and more quickly. The new daughter-in-law will come into the house of her husband’s mother, already more mature, already more of a power than she would have been as a child.” (5: 30)

“The interest of the mother is ever with the future. Women will readily understand that a single generation of accomplished is sufficient to divorce a whole race from its patrimony; and she will determine, and effectively determine, that the lot of her own sons shall bevictory, and not surrender.” (2: 85)

‘Nivedita of Sri Ramakrishna-Vivekananda’

In fact, Nivedita could realise the soul of Bharat. She reached not only every nook and cranny of Calcutta city, but also the small townships and villages all over Bharat. Like the air, transgressing all sorts of barriers, she entered every house. Imbued with the spirit of her master’s thought, she interacted with all without any inhibition, and understood the in and out of the Bharatiya life. Then she recorded all her findings, based on her own personal experience, in her book, The Web of Indian Life. It is really surprising to find a foreign lady

acquiring so much of information in so short a time.

Observations made by her about the Bharatiya family, are not only contain minute details, but also very beautiful, that really enhance our pride.

“In joint-families, one can find no maidservants for housekeeping, but all domestic chores are apportioned among the women of the household with

perfect understanding. All domestic work like cleaning, sprucing, cooking, etc. they themselves do. They also take care of small children, bathe them, feed them and administer them medicine, if needed. They all tend children like the real mother. And every relationship is qualified by a specific term, which the children also are familiar with.”

“As far as priest-craft is concerned, women come second to Brahmins. To collect flowers for the pooja, to make garlands, to spruce up the place of

worship and keep it tidy, to light lamps there twice a day, to gather articles

necessary for worship, are all treated as the unfailing devotional services of the growing girls of the household.”

She has also recorded with

appreciation an incident she witnessed, in which a mother substituting her son, laid up with fear, by offering worship on his behalf.

She could establish very close contact with families that she was privy to even very intimate matters. She writes: “Apart from the family income, the housewife will have her own separate income, which she earns by selling milk, yogurt, ghee and vegetables.” “In Bharat, the land of Rishis, multitudes of women go on pilgrimage, at times, alone, and at times, in groups.

One cannot find shyness or fear on their faces. Wearing ornaments, or without wearing them, doing Japa or chitchatting, they move ahead freely, with joyful

expression. They become friends with others without any hesitation. When those who climb up the hill and those who climb down meet, they mutually greet each other with the cry, ‘Jai Jai Kedarnath, Jai Badrinath.’ Who says women do not enjoy any freedom, they do not enjoy any position in Bharat!”

“Bharatiya woman never violates the social-code; she is not even aware how to do it. She is the progeny of the

civilisation steeped in Dharma. Dharma and charity are her destiny. Even her husband may not be aware of her vows and austerities. And even if he is aware, ‘What is so big about it, every woman does it,’ will be his response.”

Nivedita’s book, “The Web of Indian Life,” was clearly intended to present Bharat in the right perspective so as to create a true picture of it in the minds of her native people. However, now the book has turned into a national instrument that helps bring the alienated Bharatiyas once again into the national fold.

From what has been written above, it should not be misconstrued that life and work of Nivedita was confined to the sphere of women. Her area of

activity was far, far broader. In fact, she was neither an organisation nor an

institution, but her’s was a one-woman movement dedicated to the cause of the nation and Dharma. So, in the end of her every writing she termed herself

as “Nivedita of Sri Ramakrishna- Vivekananda.” Also, she was a mendicant in the truest sense. She solidly stood behind everything auspicious and positive. She was like the flame that always blazed upwards in all circumstances. She was like the golden lotus that blossomed at the touch of light. Her master, Vivekananda, once sent a benedictory message that read: “Let you be the mistress, the friend, and the servant of the future son of Bharat,” and the great time has translated his words into a reality.

(The writer is former Akhil Bharatiya Bouddhik Pramukh of RSS)

(All the quotations are from ‘The Complete Works of Sister Nivedita, published by the Advaita Ashrama. This is the English version of an article originally written in Malayalam and translated by U Gopal Maller)

Comments