The world lives on because of its dependence upon certain ideas and belief systems. These may be specific to a particular time and collapse; thereafter they might be region specific and not appeal to foreigners. But what about an idea that lives on in a continuous flow for centuries over regions stretching beyond a sub-continent? Such ideas are rare, and the rarest of them is that of Bharat.

Epitomising Cultural patriotism

Since time immemorial, Bharat is a vessel that has been holding cultural civilisation. Several manifestations of this were seen in concepts like Mahajanapadas, Janapadas, Chakravarti, Samrats, and all the judicial, political, and executive positions that have made the sustenance of this civilisational continuum possible. The political institutions, the educational framework and the social structures all functioned in harmony in an organic manner. All of these systems were in place to ensure that ideally, no strata of the society became too powerful.

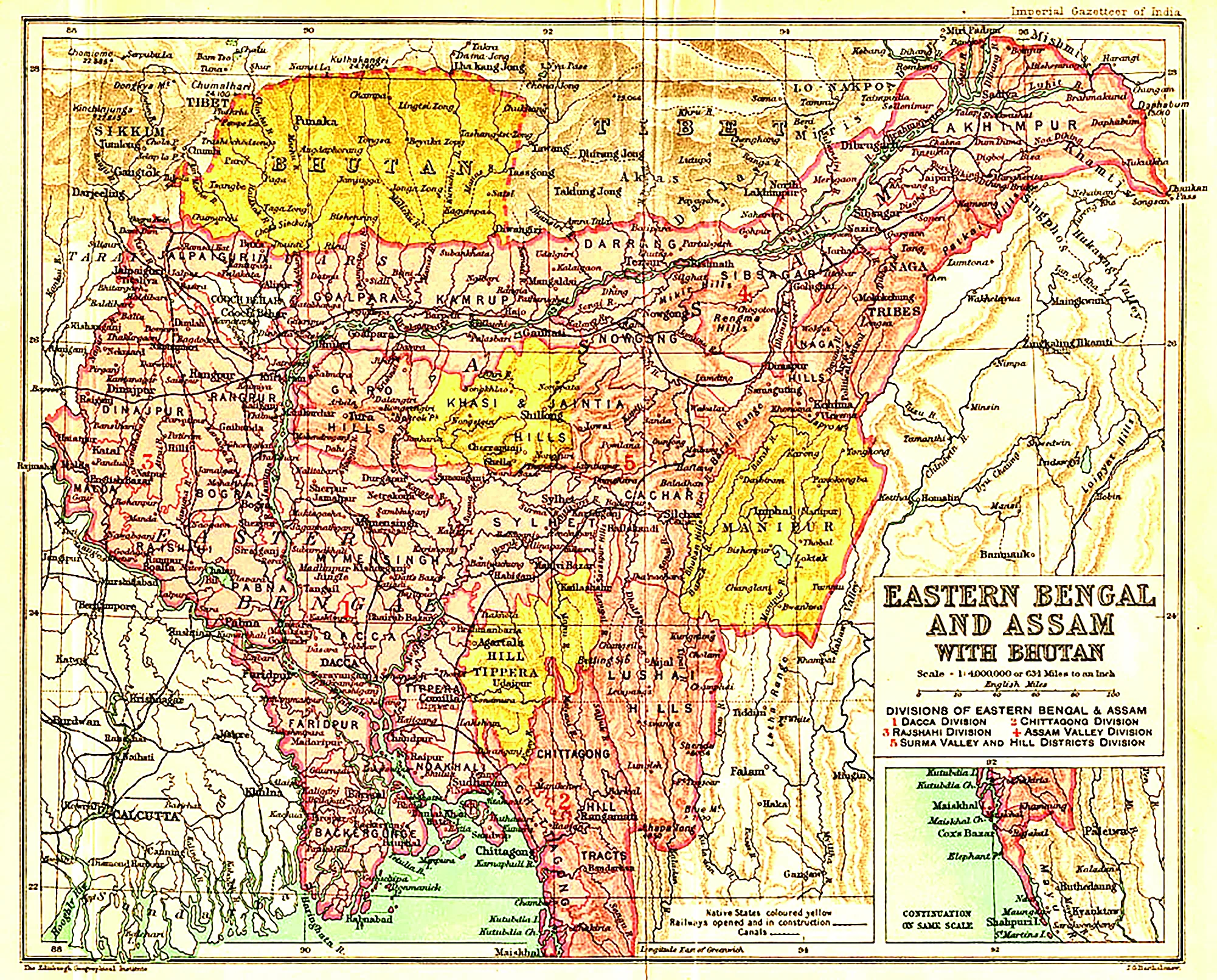

Insight into Pre-Colonial History

It was the norm in Bharat to have decentralised centres of power, trade and revenue that enabled ease of commerce and ensured distributive justice along with social welfare. These centres might have functioned under a political umbrella but customised their own people-centric policies in tune with this Bharatiyata. This was the present-day North Eastern region that could boast of several such decentralised centres of administration that existed since the beginning of recorded history (either written or oral). These seats were wielders of power, nodal points of the trade nexus, while being self-sustained with political acceptance among the people.

Glorious Kingdoms

For centuries several kingdoms like the Vermans, Pals, Kens, Chutias evolved & gained control in the region. Over a period of time, the extent of these administrative centres varied greatly. By the time the British came into contact with these centres in the early 19th Century, these units had morphed into several big and small centres of administration like Ahom kingdom, Jaintia kingdom, Dimasa-Kachari, Manipur, Tripura and Koch Behar or the smaller ones like the chieftainship system of Lushai, Garo and Khasi hills, or those of the communities of present-day Arunachal Pradesh.

In the 19th century, the British East India Company signed over 100 treaties, concerning the North East. These treaties signed between the British and regional chiefs, are testimony to this region’s diverse and illustrious administrative setup. The fact that the British had to indulge separately even with smaller chiefs who governed areas as small as a district today, sheds light not just on the number of chiefs or Kings that were in charge of small and big factions of people and territory, but also on how successful the model of smaller units of governance was.

The ideal behind these administrative centres was that of self-sustenance and self-governance, the claims were of congenial co-existence, symbiotic relations and non-aggressive contact with each other. The harmony and balance between these centres of governance and administration ensured the ease of living even in rough terrains in times when electronic and technological advancement was at a stage before its conception. The development and maintenance of safe trade routes, the ease of finance including circulation of currency, upkeep of local markets, bookkeeping, etc were all managed by these units that worked together as links of a chain. These centres were not just of administrative importance but also flourished as economic and military hotspots.

The pre-colonial history of North East was characterised by sophisticated kingdoms and unique chieftainship systems, representing a rich legacy of economic prosperity and nuanced governance. Unlike exploitative colonial rule, these indigenous centres of power operated on principles of welfare social system.

Inter-Kingdom Synergy

A hallmark of early economic sophistication is seen in Koch Behar Kingdom, which facilitated commerce through the early circulation of a silver-minted currency, known as the Narayani, in the 14th century. This currency streamlined transactions. Coins were minted by Bhutia community from the present-day Indo-Bhutan border and circulated by the Koch Behar Kingdom.

Prosperity Under Ahom

Similarly, focused on commerce and development was Ahom Kingdom, renowned for its successful resistance against Mughal invasions. Beyond its military prowess, the Ahoms championed silk industry, maintained vital trading posts and left behind magnificent architectural and civil engineering wonders, including the Talatal and Ranghar and the enduring Namdang stone bridge. Socially, the Ahoms established one of the region’s most effective models for symbiotic hill-plain relations through the Khat system, which allotted agricultural land in the plains to inhabitants of the present-day Nagaland and adjoining areas. Their administrative policy was linguistically liberal; while Sanskrit was the official language, financial records were diligently maintained in Assamese, Bengali, and Urdu to ensure widespread accessibility. Other kingdoms contributed significantly to the region’s urban and technological evolution. The Kachari Kingdom ruled a vast territory extending along the southern banks of the Brahmaputra, from Dikhow to Kallang Rivers, including Dhansiri valley and present-day Dima Hasao district. They are credited with establishing the brick city of Dimapur.

Connectivity and strategic location were key to the prosperity of the region. The Jaintia Kingdom, with its capital at Jaintiapur (in present-day Bangladesh), held a crucial position spanning both hills and plains terrain. Its location made it primarily responsible for navigating and maintaining the Surma River waterway route, which was so pivotal for transportation and revenue generation that the British attacked the kingdom in 1777 solely to gain control of it. Similarly, the Manipur Kingdom served as a major artery, housing the routes to present-day Myanmar, crossing the Chindwin basin up to Bhamo near the Irrawaddy River, boasting 2,500 years of uninterrupted economic and social contact with the Southeast Asian region, serving as a basin of cultural sustenance alongside military and technological prowess.

Trade and diplomacy also flowed through strategic transit points. The Gobha (Tiwa) Kingdom, though often defined as a vassal state between the Ahom and Jaintia Kings, held strategic importance. Its seat was one of the Nauduars (Nine Gates) on the southern side of the Brahmaputra Valley, making it a critical transit point for diplomacy, politics, and economy between the Jaintia and Ahom kingdoms.

Flourishing Chieftainship structure

Beyond the kingdoms, exceptional models of people-centric governance flourished in the form of Chieftainships. These chiefs were essentially people’s representatives, operating with an advisory council that typically included a blacksmith, a priest, and village elders. The Khasi Hills Chieftainship was an impressive example of this structure, governed collectively by an entente of chiefs from Sohra, Nongstoin, and other regions under a similar administration without a central ruling king. The Khasi hills were rich producers of coal, iron ore, limestone, and slate, and the people were highly skilled in mining, metallurgy, ship building , and transportation. Despite the British policy of coercion adopted in 1826, they were compelled to sign separate treaties with all these chiefs, underscoring the chiefs’ strong sense of self-governance. The Chiefs of the Lushai Hills were particularly remarkable, not only protecting travellers and traders but also acting as exceptional freedom fighters, battling the British for seven decades without signing a treaty. In the Naga Hills, the chieftainship was unique for its social development, highlighted by a Gurukul-like education system, and the people were fierce warriors who defended the region against Islamic invasion.

Even the Chiefs of present-day Arunachal Pradesh, like the Raja of the Chari Duar, while sometimes under the umbrella of Ahom kings for maintaining trade routes and safety in exchange for a monthly stipend, were fundamentally independent, evidenced by the treaties signed with the British by communities like the Abor (Adi), Aka, Khampti, and Singphos, establishing their intent for self-governance.

In essence, the pre-colonial administrative centres of this region were not merely symbols of a transactional relationship where citizens paid taxes and administrators filled coffers, as was largely the case under colonial rule. They represent a nuanced, sophisticated social and economic system that pioneered currency, urban development, architectural marvels, diplomatic models, technological advancements, and people-centric governance. The pre-colonial heritage and legacy stand as an unevaluated asset, providing crucial context for understanding the extent of what was possessed and what was consequently lost or ruined upon the advent

of the colonisers.

Comments