During the Christmas weekend of 2004, Anil Sharma, popular as the director of the extremely successful Sunny Deol starring Gadar and its sequel, released a film called Ab Tumharein Hawaalein Watan Saathiyo, featuring Amitabh Bachchan, Akshay Kumar, Danny Denzongpa and Bobby Deol. While it is largely forgotten now, let me run you through how craftily the pro-Pakistan narrative was weaved into the script. The story carefully separated terrorism from the Pakistani state, repeatedly showing terror groups as “independent elements” with no connection to the Pakistani govt or army.

Sharma, in the Gadar franchise, also does the same actually, if you carefully analyse how things are played out in the so-called nationalistic action romances. Interestingly, this engineered framing in Hindi celluloid largely mirrored Pakistan’s official global narrative. More importantly, in the aforementioned movie, the Pakistani Army was portrayed not just as neutral but as morally upright and heroic. It cooperated with the Indian Army to protect the Amarnath Yatra, positioned itself as equally invested in Indian civilian safety, and was shown disciplining terrorists internally. A Pakistani officer, played by Denzongpa, beats up terrorists trying to attack Amarnath Yatris, and even takes a bullet to save Indian officer Akshay Kumar while “Allah-hu-Akbar” plays in the background. The systemic reality of cross-border terrorism birthing from Pakistan was diluted into a ‘bad apples’ theory. The conflict was reduced to misunderstandings between two well-meaning armies, resolved through sher-o-shayari and personal friendships.

Instances of pseudo-nationalistic works are rife in bollywood. Main Hoon Na, Raazi, Pathaan, Ek Tha Tiger and so on and so forth. I am not even mentioning My Name is Khan, Haider or Shaurya, which were vicious propaganda served in the name of cinema, albeit pretty subtly and with dollops of monkey balancing

Instances of such pseudo-nationalistic works are rife in the Hindi film industry. Main Hoon Na, Raazi, Pathaan, Ek Tha Tiger and so on and so forth. I am not even mentioning My Name is Khan, Haider or Shaurya, which were vicious propaganda served in the name of cinema, albeit pretty subtly and with dollops of monkey balancing. The operative word here is subtle. A technique used for dishing out lies about the Indian army and the state for visual consumption gradually through cinema that perpetrated inaccuracies in order to pander to the largely pro-Pakistan mentality prevalent in the Hindi film industry. We didn’t even realise when that tinsel town became Urduwood (dominated by writers invested in sketching Hindu characters as evil with alacrity and ensuring the sympathetic lens is always drawn on Muslims, Hindi dialogues getting crowded by Urdu usage, Qawwalis and Pakistani singers influencing music made here and of course the glorification of 786 post an angry man sporting the ‘famous’ billa in Yash Chopra’s Deewar), after being parodied as Bollywood, honestly.

Aditya Dhar, easily one of the best Indian directors right now, deserves to be celebrated not only because his work is acutely authentic, but also because he dared to expose how Pakistan is a breeding ground of radicalism and terror, the rationale of which lies in its motto of Hindu hatred

Yes, we have had a plethora of movies cheering for ‘aman ka tamaasha‘, I mean ‘asha’. Even in the Vicky Kaushal and Alia Bhatt starrer Raazi, director Meghana Gulzar changed the ending and showed that Sehmat is deeply saddened by what she did. But as per Harinder Sikka, the author of ‘Sehmat calling Sehmat’, from where Raazi was adapted, the protagonist had no regrets. For, this is how Indian spies are trained to be. Fiercely dutiful, extremely tough mentally and faithful to India, an emotion channeled by the innate love towards their motherland. In Sikka’s book, Sehmat returns to India with a VIP welcome, is showered with rose petals, and kneels to salute the Indian flag. In the movie, Sehmat returns in a depressed, haunted state, focusing on the psychological toll of her mission, with no grand patriotic welcome or flag-saluting scene. The author, in several interviews recorded later, revealed that Gulzar “intentionally” made these changes. Sikka went on to explain, “The film’s ending was ‘pro-Pakistani” and erased a crucial line from the book where Sehmat says, ‘I’m sorry Abdul, but I love my country more’.”

This kind of whitewashing to suit a certain agenda wasn’t new. But yes, the cup of lies seems to have brimmeth over! Even if the Leftist and Islamist ecosystem that fanned such warped and illogical falsifications and handed out the rose-tinted glasses through which Pakistan would be depicted in mainstream Hindi cinema tries to deny it! Hence, the meltdown of this human hub of hypocrisy infected by the disease of denial is profoundly amusing. The hornet’s nest has been triggered by the latest sensation to have hit the theatres. Dhurandhar, Aditya Dhar’s bold spy thriller that is unapologetically nationalistic and dares to show how Pakistan sponsors and nurtures terrorism. And in doing so pretty effectively, it depicts how India reeled as a soft state under the Congress leadership and how defense policies and hitback strategies (aided by Indian RAW agents infiltrating terror depos of Pakistan) underwent change and amplification when the government changed.

With the tremendous adulation that the director, the entire cast and crew has received for their efforts, there isn’t even a doubt whether the movie is worth watching or not. Dhar is building things up bit by bit. It is called mastering the craft!

While the main hero in Dhurandhar is the impeccable writing, bolstered by indepth research and accuracy, the casting worked wonders as well. Ranveer Singh doesn’t need validation when it comes to histrionics. No matter how lopsided his offscreen persona is, this man knows how to make love with the medium he is engaged in. I have always enjoyed his performances (barring a few films) and here too, Ranveer is in top form. But that’s not the point. The narrative is so balanced that Dhar doesn’t let the protagonist take away all the honours. His pen sketches every character attentively to make the ensemble wholesome. For instance, not many are talking about the work Rakesh Bedi invested here but his years of experience has engineered an effortlessly delightful character. Kudos to Dhar for assigning him the role of Jameel Jamali, drafted based on the real life Nabil Gabol.

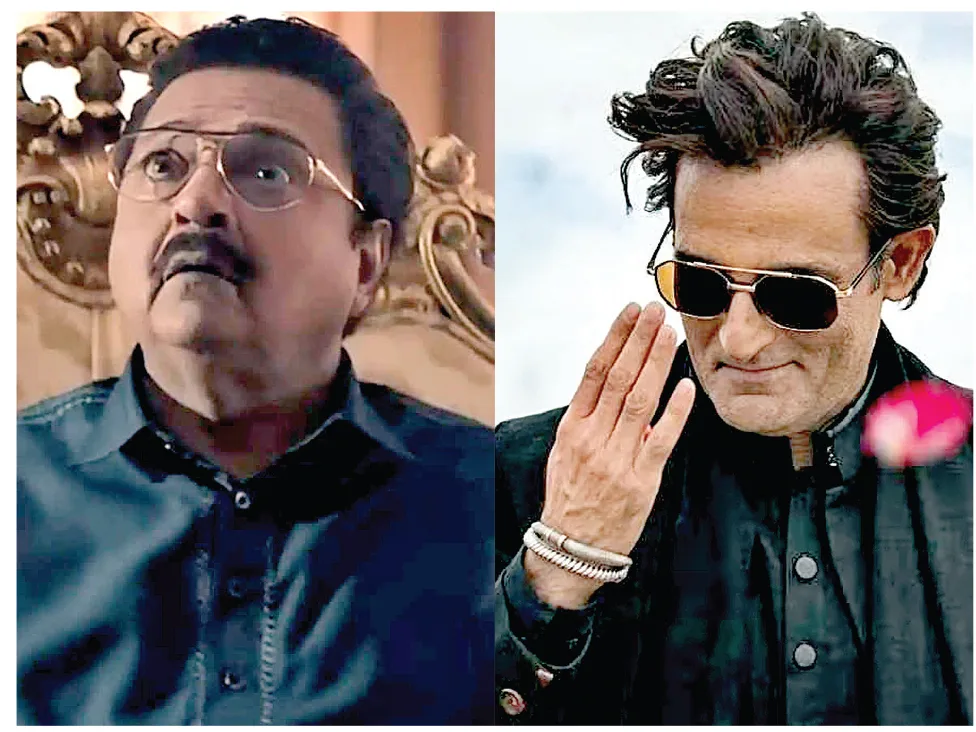

Then there’s Sanjay Dutt, languishing in a space where nothing extraordinary was expected from him. And yet Dhar shows what that man still has left as a performer, his criminal past notwithstanding. Here, applause is due for Shashwat Sachdev, the man behind the music of the movie. If you were floored by the soundtrack, the BGM and the mashups will take your breath away. Dutt’s introductory scene is brought alive by an extremely popular track from our childhood. Watch the movie and hear it yourself!

R Madhavan’s portions crucially take the story forward even as it shows how a true nationalist is rendered helpless when the state doesn’t muster enough courage to battle terror ripping apart his country. Arjun Rampal has been given a part that clearly will be the cynosure of attention in the second part of this espionage spy thriller verse. As for me, the actor who stands out in the motley of passionate performances is Akshaye Khanna. The man is a vibe! And to think that this terribly underrated talent with no social media presence, hardly any media interviews, zero paparazzi interactions would have a screen presence this magnificent and commanding. Khanna started 2025 with a Bang (Chhaava) and ended the year immortalising the menacing Rehman Dakait with a restrained, deadly and mesmerising performance.

A film like Dhurandhar matters. India has thousands of years of civilisational depth, extraordinary real-world heroes, untold military and intelligence stories, and a unique worldview shaped by history, philosophy, and resilience. Yet, our cinema rarely presented these narratives with the same confidence or strategic

intent that Hollywood did

Dhar, easily one of the best Indian directors right now, deserves to be celebrated not only because his work is acutely authentic, but also because he dared to expose how Pakistan is a breeding ground of radicalism and terror, the rationale of which lies in its motto of Hindu hatred. The originality wouldn’t have been possible without the research assistance by Aditya Raj Kaul and this is where Dhurandhar is starkly unique from what the Hindi film industry has been churning out in the name of spy thrillers. More importantly though, it needs to be established where a film like this matters for India in the larger scheme of things.

Let’s cite Hollywood that has mastered something that most countries still underestimate. Its biggest films are not just entertainment. They are soft power. Blockbusters like Top Gun, Argo, Zero Dark Thirty, Black Hawk Down, Saving Private Ryan, and American Sniper made hundreds of millions of dollars, won Oscars, and became cultural icons. But they also did something else. They shaped how the world sees America. Many of these films were produced with Pentagon or CIA involvement. Scripts were polished, scenes were guided, and narratives were shaped to portray the United States as heroic, disciplined, morally righteous, and strategically essential. The messy parts of history were softened or left out entirely.

This storytelling strategy did not just entertain global audiences. It built trust, admiration and influence, thus making Hollywood one of the pillars of American soft power. This raises an important question for us: Where are India’s global storytelling vehicles? Where are the films that present India’s intelligence, strategy, innovation, courage, and leadership to the world? And while looking for the answers you will realise why a film like Dhurandhar matters. India has thousands of years of civilisational depth, extraordinary real-world heroes, untold military and intelligence stories, and a unique worldview shaped by history, philosophy, and resilience. Yet, our cinema rarely presented these narratives with the same confidence or strategic intent that Hollywood did. America understood early that whoever controls the narrative shapes global perception. And whoever shapes perception strengthens their geopolitical influence.

India never lacked talent. But coordinated narrative ambition was conspicuous by its absence. Dhurandhar represents a shift: a project designed to show Bharat as capable, intelligent, and strategic. A film that can build soft power, inspire the youth, and occupy cultural space that has long been dominated by American storytelling. While this is not about competing with Hollywood. It is about telling our own story on our own terms, correctly. Soft power is not built by GDP numbers or military strength alone. It is built by stories. And the time has come to tell more of them with scale, confidence, and purpose.

Comments