KOLKATA: Fourteen years after the Trinamool Congress (TMC) swept to power with promises of “Paribartan,” West Bengal finds itself at a crossroads where economic stagnation, social unrest, and investor flight converge into a full-scale governance crisis. Numbers stark, unforgiving, and unprecedented tell a story of a state steadily losing its economic backbone and civic confidence.

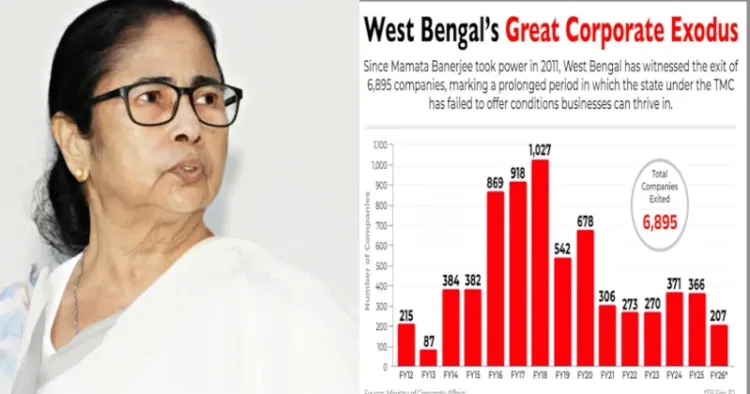

Between 2011 and 2025, 6,895 companies moved their operations out of West Bengal a trend economists describe as structural outmigration, not a cyclical fluctuation. What began as a trickle in the early years of Mamata Banerjee’s rule accelerated into a steady corporate evacuation.

𝐖𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐁𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐚𝐥 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫. 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐍𝐔𝐌𝐁𝐄𝐑𝐒 𝐭𝐞𝐥𝐥 𝐲𝐨𝐮 𝐰𝐡𝐲.

From industries shutting shop to women living in fear — the state’s decline under TMC has only grown deeper and more alarming.

🔴 6,895 companies have exited Bengal since 2011.… pic.twitter.com/pcXrucyd3l

— BJP (@BJP4India) December 4, 2025

The year 2017–18 stands out as the high-water mark of industrial distress, with over 1,000 companies closing or exiting in a single year. But this was not an anomaly the preceding and following years show the same pattern of flight, each reinforcing the perception that Bengal’s business environment was deteriorating, not recovering.

Even in the last six months alone, 207 companies have left, confirming that the trend is not slowing it is deepening.

Industry observers warn that an exodus at this scale typically reflects issues beyond market cycles, “Companies don’t leave states. They leave uncertainty,” said one senior industrial analyst who requested anonymity.

If decades of union trouble, infrastructure stagnation, and bureaucratic hurdles pushed businesses away, the government’s move on April 2, 2025, may have pulled the last remaining support beams out from beneath West Bengal’s economy.

The Revocation of West Bengal Incentive Schemes and Obligations in the Nature of Grants and Incentives Bill, 2025 abruptly scrapped all industrial incentives dating back to 1993 and did so retrospectively.

For nearly thirty years, successive governments had offered:

- tax holidays

- capital subsidies

- interest reimbursement

- electricity duty waivers

- SGST reimbursements

- land subsidies

- employment incentives

Companies invested based on these promises many with long-term financing arranged on the assumption of government-backed support.

Major industrial groups estimate hundreds of crores in losses. The Birla Group and Dalmia Bharat have pegged their combined exposure at over Rs 430 crore, and dozens of firms are preparing legal challenges. For smaller companies, the losses may be existential.

Legal experts argue that revoking long-standing incentives undermines:

- the doctrine of legitimate expectation

- the principle of non-retroactivity

- the sanctity of contracts between the state and private parties

A former judge described the law as “administrative dynamite” detonating investor confidence not just in Bengal, but potentially across states observing the fallout.

The state’s distrust toward capital did not begin with the TMC. During the 35-year Communist era, industry was often cast as an adversary. Strikes, militant unionism, political intimidation, and instances of arson drove away major business houses most infamously the Tata Nano project in Singur, which cemented Bengal’s reputation as a difficult state for investors.

When Mamata Banerjee took power in 2011, many hoped for a reset. But industry leaders say the pattern did not improve. Singur, once a symbol of resistance, became an omen.

Economists often warn that capital avoids not just bad policy, but bad environments. The high-profile incidents of the last few years from Sandeshkhali to recurring cases of harassment, trafficking, and politically shielded violence have contributed to a perception that law and order is deteriorating.

Women’s groups in Kolkata say fear has become part of daily life, “We are not safe on the streets, we are not safe at night, and we are not safe when we go to the police,” said a social worker from North 24 Parganas. For many households, these issues are no longer isolated events they shape decisions about employment, migration, and long-term plans.

As industries shut down and jobs evaporate, Bengal’s youth especially in districts like Murshidabad, Malda, Howrah, and Birbhum have increasingly left the state for work in:

- Kerala

- Karnataka

- Maharashtra

- Gujarat

- Delhi

- Tamil Nadu

Unemployment, particularly among educated youth, remains one of the state’s deepest and most unaddressed wounds. Professors in Kolkata call it “the silent demographic hemorrhage.”

Modern development theory is clear:

- Incentives help offset market failures.

- Policy certainty attracts long-term capital.

- Law and order strengthens investor confidence.

- Social stability sustains economic ecosystems.

- But Bengal is moving counter to these principles.

Global contrast

- The US spends $30 billion annually on business incentives.

- India’s PLI scheme has triggered nearly Rs 1.76 lakh crore in new investments.

At a time when countries and states are aggressively competing for capital, West Bengal has chosen to pull the rug out from under investors.

Economic downturns do not happen in isolation. They spill into daily life from the markets to the schools to the very sense of security people once took for granted. With multiple industrial houses challenging the 2025 Act in the Calcutta High Court, the judiciary may become the arena where Bengal’s economic future is decided.

Comments