Since 2018, the United States has steadily tightened its investment screening laws to stop strategic rivals, especially China, from infiltrating sensitive sectors such as semiconductors, telecommunications and defence-linked services. But it was not always this vigilant. In 2016, veteran US intelligence reporter Jeff Stein received information that an obscure insurance company selling liability cover to FBI and CIA officers had been unexpectedly taken over by a Chinese-linked entity. According to Stein’s account, the revelation left national security observers stunned. The insurer in question, Wright USA, had been quietly acquired in 2015 by the Fosun Group, a private corporation widely believed to operate in close alignment with China’s political leadership. The implications became immediately apparent. Wright USA possessed sensitive personal and professional data belonging to some of America’s most secretive intelligence personnel. With its acquisition by Fosun and its parent firm Ironshore, Washington found itself unsure of who now controlled this trove of classified-adjacent information. Wright USA, it turned out, was only one case among many.

Reports now reveal exclusive access to new datasets showing how China’s state-directed capital has been flowing aggressively into wealthy countries for years, purchasing an array of assets across the US, Europe, Australia, and the Middle East. Far from being restricted to developing economies, China has become the world’s most expansive overseas investor, giving Beijing the ability to influence, leverage, and in some cases dominate sensitive industries and cutting-edge technologies. The details of China’s spending abroad remain classified within Beijing’s system, deliberately hidden from public scrutiny. According to information in the Wright USA case, the acquisition was not merely a private deal. Fresh data shows that four major Chinese state banks financed a $1.2 billion loan routed through the Cayman Islands to facilitate Fosun’s purchase. Stein eventually published the story, triggering an immediate response in Washington. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) launched an inquiry, and soon after, Wright USA was sold back to American owners under circumstances that remain unclear.

High-ranking US intelligence officials confirm that the Wright USA episode was among the catalysts that pushed the Trump administration to overhaul and tighten America’s foreign investment laws in 2018. What few realised then was that this acquisition was part of a far broader, systematic effort by Beijing to buy its way into strategic sectors worldwide. Researchers at AidData, a Virginia-based analytical lab focused on tracking cross-border governmental spending, have spent four years mapping China’s global financial activity. Their newly compiled dataset, prepared by 120 researchers, represents the first known attempt to account for the full scale of China’s state-backed overseas investments. Reports indicate that China has funnelled approximately $2.1 trillion abroad since 2000, split almost evenly between developed and developing nations.

Experts describe China’s financial system as unprecedented in scale and centrally orchestrated. With the world’s largest banking network, surpassing the combined systems of the US, Europe, and Japan—Beijing exercises extraordinary control over interest rates, credit flows, and the strategic direction of its state banks. Analysts note that such tight state control enables China to channel vast resources into geopolitical priorities that no other major economy could sustain. Some of China’s acquisitions in advanced economies appear to have been motivated by profit. Others closely align with Beijing’s strategic industrial ambitions, particularly those articulated in the 2015 “Made in China 2025” programme, a sweeping initiative designed to secure dominance in ten high-technology sectors, including robotics, electric vehicles, and semiconductors. Although public references to the programme were toned down following global backlash, analysts confirm that it continues to guide Beijing’s ambitions, reinforced by successive plans on artificial intelligence, smart manufacturing, and China’s 15th Five-Year Plan. Only last month, Chinese leaders reaffirmed their drive toward accelerating technological self-reliance and reducing dependence on foreign innovation.

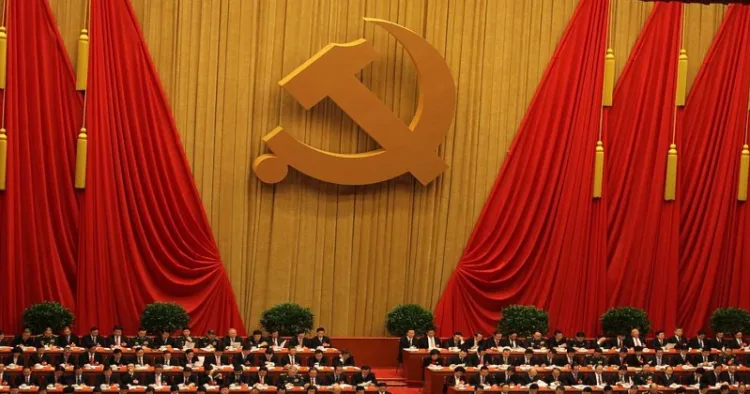

AidData’s findings show that a significant share of China’s state-directed overseas funding is concentrated precisely in the sectors highlighted in these strategic blueprints. Earlier investigations revealed that Chinese state banks financed the acquisition of a British semiconductor firm, a pattern consistent with Beijing’s global hunt for critical technologies. Governments across the US, UK, Europe, and other advanced economies have scrambled in recent years to strengthen their investment screening frameworks. According to AidData’s Brad Parks, many Western governments had initially misread Chinese acquisitions as isolated commercial activities by independent firms. Over time, however, they realised these moves reflected a coordinated effort by the Chinese Communist Party to expand influence and extract sensitive technology under the guise of normal business transactions. China’s strategies often relied on opaque structures, offshore intermediaries, and shell entities, meaning the investments were technically legal, yet strategically designed to obscure Beijing’s hand.

Chinese diplomatic officials continue to assert that Chinese companies operating overseas follow local laws and contribute to global development. However, analysts argue that these statements mask a broader strategy of covert global expansion that threatens national security interests worldwide. AidData’s database also shows a shift in China’s global investment geography. Beijing increasingly directs funds toward wealthy countries that are willing, or in some cases unprepared to scrutinise Chinese capital. A notable example is Nexperia, a semiconductor firm in the Netherlands that became embroiled in controversy after its takeover by Chinese interests. The database confirms that in 2017, Chinese state banks arranged an $800 million loan to back a Chinese consortium’s purchase of Nexperia. By 2019, the company’s ownership was transferred to Wingtech, another Chinese firm. Dutch authorities later intervened, citing concerns that Nexperia’s strategic technologies could be siphoned off into China’s broader semiconductor ecosystem.

As a result, the Dutch government effectively split Nexperia’s operations, severing its Dutch arm from its Chinese manufacturing links. The company subsequently informed the world that its Chinese branch was no longer following governance protocols nor adhering to standard oversight mechanisms, an illustration of the governance risks that European policymakers fear. In the Netherlands, the Nexperia case fuelled an intense debate. Traditionally a champion of open markets and free trade, the country has now begun reassessing its engagement with China, recognising the geopolitical vulnerabilities inherent in uncontrolled investment flows. Analysts caution, however, against assuming that all Chinese firms operate as uniform extensions of the state; many private companies simply seek profit and are caught in the geopolitical crossfire. Yet the overarching concern remains: China’s system blurs the line between state and enterprise, enabling Beijing to leverage private firms for strategic ends.

The critical question is whether China’s head start in securing access to sensitive technologies and strategic industries means that the global contest is already decided. Experts argue that the race is far from over. Chinese companies continue to target acquisitions worldwide, but they now face far more scrutiny and resistance. Advanced economies, once complacent, are shifting from reactive to preventive strategies, moving from defence to offence in safeguarding their industries. Major G7 countries are rapidly adjusting, adopting more aggressive screening, building alliances to protect sensitive technologies, and structuring mechanisms to counter China’s covert influence.

The world is entering a new phase of economic and technological rivalry, one defined not by open trade but by strategic vigilance. And while Beijing’s covert investment strategy once unfolded unnoticed, governments today recognise the stakes and are preparing for the next round of a long, high-stakes contest.

Comments