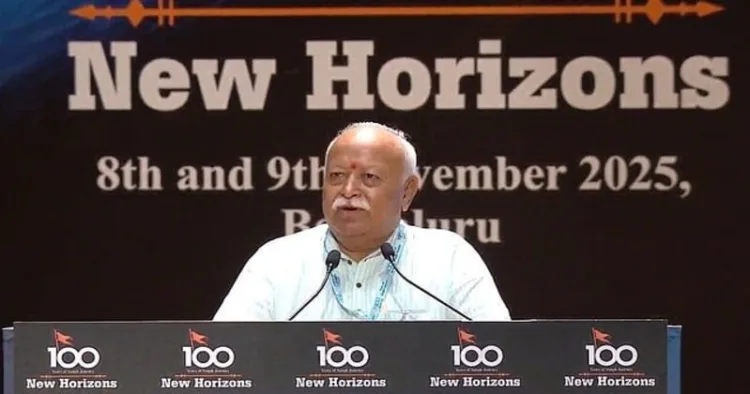

Every great civilisation faces a moment when it must pause and ask what truly holds it together. India, with its ancient plurality and restless modernity, stands precisely at such a crossroads. The recent two-day address of Dr Mohan Bhagwat, Sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), in Bengaluru was not a partisan proclamation but a civilisational reflection, an appeal to restore the moral and emotional glue that keeps this vast nation from unravelling. His theme was social cohesion, his warning was about the “Breaking India” forces that thrive on our divisions, and his message was both ethical and existential: a society that forgets its shared consciousness endangers its freedom.

Bhagwat’s argument was less political than philosophical. He spoke of unity as a living emotion rather than a mechanical arrangement of interests. For him, the strength of Bharat lies not in power or policy but in sanskriti, the culture that teaches coexistence, restraint, and respect. India, he reminded, has never been a nation forged by conquest but by continuity; its bonds are not legal contracts but moral understandings. When these subtle fibres weaken, no constitution or coercion can prevent disintegration. It was a call to remember that cohesion begins in the mind before it manifests in the state.

The term “Breaking India”, often misunderstood, was used by Bhagwat to describe more than overt hostility. It referred to an ecosystem of ideas, attitudes, and influences that exploit India’s internal differences and cultivate self-doubt about its civilisational worth. He cautioned that cultural colonisation, in the age of social media and ideological mimicry, is far more dangerous than physical invasion. The mind, once deracinated, becomes easy prey for narratives that mock the very foundations of Indian selfhood. His remedy was not aggression but awakening, a revival of confidence rooted in moral discipline and cultural empathy.

The strength of Bhagwat’s position lies in its ethical clarity: he sees social disharmony not as a failure of governance but as a failure of character. When families disintegrate, when self-restraint collapses, when the pursuit of comfort replaces the pursuit of meaning, the social organism begins to decay. The RSS ideal of vyakti nirmaan se rashtra nirmaan, nation-building through individual refinement, emerges from this moral logic. Cohesion, therefore, cannot be legislated; it must be cultivated. And in that sense, the Sangh’s century-long experiment in social service and voluntary organisation has attempted to rebuild trust from the ground upward, not from the corridors of power.

Yet, any serious reader must also engage the philosophical tension implicit in this vision. When cultural revival is presented as the remedy for division, it risks sliding into cultural dominance unless constantly balanced by humility. Bhagwat’s invocation of the term “Hindu” as the civilisational identity of India is meant, in his view, as an inclusive expression — a recognition of shared ancestry rather than religious exclusivity. But the challenge lies in perception: if the cultural centre becomes too pronounced, those at the margins may feel unheard. Social cohesion demands not assimilation but reciprocity. India’s unity has always thrived not by dissolving differences but by harmonising them.

Bhagwat’s address, when read generously, also acknowledged this. He called for erasing caste arrogance, nurturing compassion, and cultivating the habit of dialogue. His stress on humility and service suggested that the real obstacle to harmony lies not in external conspiracies but in internal hierarchies — the unspoken barriers that distance one Indian from another. The “Breaking India” forces, he implied, succeed only when these invisible walls remain intact. In urging reform within, he extended the concept of nationalism from the geopolitical to the moral — from protecting borders to purifying conscience.

To view this as a mere ideological sermon would be to miss its resonance with a larger global anxiety. Across the world, societies are fragmenting under the weight of polarisation, misinformation, and rootlessness. Bhagwat’s critique of cultural self-alienation thus mirrors a global concern: the erosion of meaning in an era of abundance. His emphasis on vegetarianism, simplicity, and moral restraint, though often reduced by critics to cultural prescriptions, are, in essence, arguments for ethical minimalism in an age of excess. Whether one agrees or not, the principle he invokes is universal: that inner discipline is the first act of social reform.

The notion of “Breaking India” can, of course, be misused if invoked indiscriminately. Not every disagreement is sedition, not every critic an adversary. A democracy that aspires to moral maturity must learn to separate debate from disruption. Bhagwat’s moral appeal thus needs the complement of institutional openness. Cohesion cannot be achieved through uniformity of opinion but through unity of purpose — the willingness to serve the larger good despite ideological differences. The RSS vision, when stripped of polemic, is an invitation to rediscover that moral fraternity which transcends faith and party alike.

India today stands between two currents, the gravitational pull of its ancient pluralism and the centrifugal drift of modern fragmentation. The task, as Bhagwat implied, is not to choose between them but to reconcile them. To modernise without deracinating, to be plural without being apologetic, to be confident without being coercive, this is the civilisational balance that defines India’s strength. The struggle against “Breaking India” forces, therefore, is not a battle of slogans but of sensibilities; it is the slow, silent work of cultivating respect, responsibility, and restraint in the national temperament.

In the final measure, Dr Bhagwat’s address was less about institutions and more about imagination, the imagination of Bharat as a moral idea rather than a political entity. Whether one stands with or apart from the RSS, one cannot deny the urgency of his question: can a nation endure when its people lose the capacity to trust each other? His answer, drawn from a century of Sangh experience, was both simple and profound, only when the individual heart becomes disciplined in empathy can society rediscover coherence.

To weave India together again, Bhagwat seemed to say, we must first mend the threads within ourselves. And perhaps that, in the end, is the most radical idea of all, that national renewal is not born in power but in conscience, not in uniformity but in understanding. The battle for Bharat’s unity, then, is not on the borders or in parliaments, but in the moral imagination of its citizens.

Comments