The car bomb that ripped open the evening in Delhi near the Red Fort on November 10, has focused a harsh light that you do not need RDX to make a mass-casualty bomb. Investigators now say the device used ANFO ammonium nitrate fuel oil an improvised but devastating explosive whose destructive power depends on bulk rather than brute chemical force. The seizure of hundreds of kilograms of ammonium nitrate in Faridabad hours before the blast has hardened the central question facing Indian security agencies, how did a terror cell amass industrial quantities of a legally traded fertiliser-grade chemical and convert it into a weapon of mass murder?

Official casualty figures remain in flux reports have varied between nine and a dozen dead and many more injured but the human toll and the symbolic brazenness of an explosion beside one of India’s most sensitive national monuments are indisputable. What began as alarm at rumours of RDX quickly shifted to grim clarity: this was not a surgically compact military-grade charge, but a low-tech, high-volume bomb that kills by sheer scale.

A joint operation by J&K and Haryana police in Faridabad last weekend recovered what authorities now say was approximately 350 kg of ammonium nitrate from two houses linked to a Dr. Mujammil Shakeel (said to be employed at Al-Falah Hospital, Faridabad) and two associates, Dr. Adil Ahmed Rather and Dr. Shahina Shaheed. Intelligence sources quoted by local media also tie the cache to alleged Jaish-e-Mohammed operatives. Law-enforcement officials say more than 2,000 kg of other explosive material was seized in the same operation.

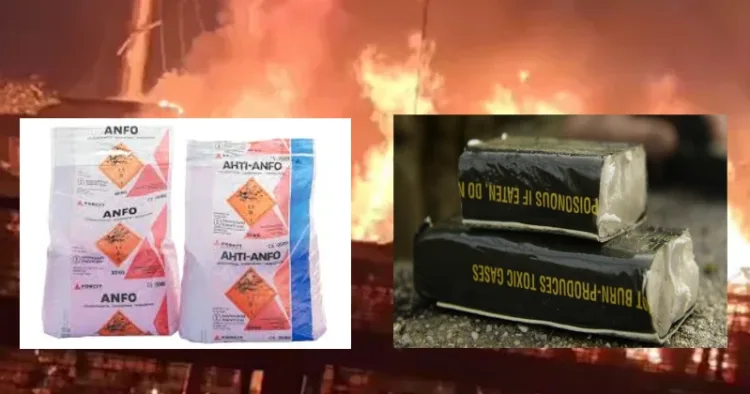

When those raids were confirmed on the morning of 10 November, initial panic stemmed from reports that RDX had been recovered a fear that would be natural, given RDX’s reputation as the explosive of precision, power and terror. But forensic examination indicated ammonium nitrate, not military-grade RDX. The distinction is critical: RDX is a compact, high-brisance explosive whose shattering shockwave is measured in kilometres per second. ANFO, by contrast, is a “non-ideal” explosive whose destructive potential comes from mass, confinement and the right triggering arrangement.

RDX vs ANFO

RDX (cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine) is a military-grade secondary explosive used in plastic explosives such as C-4 and in modern warheads because of its very high detonation velocity and brisance. By weight, RDX far outperforms conventional explosives such as TNT with a relative effectiveness (RE) often cited around 1.5 to 1.6, and obliterates hardened targets with concentrated shock waves. RDX’s production, storage and movement are tightly controlled and generally restricted to defence establishments for a reason: a few kilograms can level structures and fragment steel.

Ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) is chemically very different. It is primarily an agricultural fertiliser and an oxidiser; in its pure form it is not an explosive but, when mixed with a fuel like diesel or kerosene (forming ANFO), it becomes a powerful blasting agent. ANFO’s RE is far lower around 0.75 and its reaction is slower and less concentrated than RDX. That makes ANFO inherently less “brisant” per kilogram: it damages by producing massive volumes of hot gas and sustained pressure, not by the sudden, shattering supersonic shock of RDX. In short: RDX is about quality of energy in a small package; ANFO is about quantity of energy delivered at scale.

Crucially for terrorists, ANFO has two terrible advantages: it is cheap and it is widely available. Fertiliser-grade ammonium nitrate is sold openly for agricultural use; diesel and kerosene are ubiquitous. When combined and confined as in the case of truck or car bombs ANFO can create horrific destruction. The Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, which killed 168 people, used some 2,300 kg of ANFO. The Beirut port catastrophe of 2020, an accidental detonation of stored ammonium nitrate, illustrated how catastrophic even improperly stored fertiliser can be.

Why initial ‘RDX’ reports caused alarm and why ANFO is still devastating

Reports of RDX trigger different alarms. RDX implies access to defence-supply chains or theft from secure facilities, and suggests a professional, perhaps externally aided operation. ANFO, while “amateur” in chemical sophistication, is no less lethal in effect when used in mass and properly concealed. Investigators say the Red Fort device used an external detonator possibly manually triggered and was packed into a Hyundai i20. That profile is consistent with a suicide or manually triggered car bomb using ANFO: a relatively simple assembly, but one that, if made with hundreds of kilograms of material, becomes a weapon that can level vehicles, shred nearby structures and create mass casualties.

This means authorities have two separate but connected problems: one, tracking and preventing diversion of dual-use chemicals like ammonium nitrate; and two, stopping extremist networks from acquiring the organisational capacity to collect, store and move such quantities without detection.

India classifies ammonium nitrate and mixtures containing more than 45 per cent of the compound as explosives under the Explosives Act, 1884. Rules notified in 2012 and amended in 2021 demand licences for manufacture, storage and transport, and bar storage in populated non-industrial areas. In practice, however, ammonium nitrate is widely sold as fertiliser and used across agriculture, mining and construction and supply chains are complex, fragmented, and porous. The Faridabad seizures and the fact that several hundred kilograms could apparently be gathered in domestic properties linked to medical professionals raise a stark question: are licensing and monitoring systems failing, or are networks exploiting legitimate supply chains through small-scale purchases aggregated into dangerous stockpiles?

Security experts say the answer is both. Complete bans would cripple farmers and industry; lax enforcement invites diversion. What appears to have happened in this case is classic “aggregation laundering” legal small purchases funnelled into illicit stockpiles. That pattern mirrors other terror attacks in India and abroad: the 2006 Mumbai train blasts, the 2010 Pune bombing, the 2011 Mumbai attacks and international cases such as Breivik’s Norway bomb and Oklahoma City.

Another alarming pattern is hybridisation: terrorists have repeatedly combined RDX with ammonium nitrate in past attacks to use RDX’s brisance as an initiating booster and ANFO’s volume to amplify destruction. Investigators are therefore meticulously analysing residues from the Red Fort blast to confirm whether pure ANFO alone was used or if traces of RDX or other high explosives are present. The presence of RDX would point to a different level of supply-chain compromise and potentially international connections.

On November 13, forensic analysis of DNA samples collected from the charred remains at the Red Fort blast site confirmed a match with those of Umar Mohammad’s mother, conclusively establishing the identity of Dr. Umar Mohammad alias Dr Umar Un Nabi a medical professional from Pulwama, J&K, as the perpetrator of the attack. The explosion, which occurred at 6:52 p.m., killed nine people and left nearly a dozen others grievously injured, making it one of the deadliest terror strikes to hit the national capital in recent years.

According to investigators, Dr Umar Un Nabi, who was associated with Al-Falah University in Faridabad, was in contact with a Türkiye-based handler codenamed ‘Ukasa’, believed to have coordinated the operation remotely.

Comments