Gurudev Rabindranath in his essay The religion of the Artist (1924) wrote, “I was born and brought up in an environment of three movements, all of which were radically awakening… there was a second movement… Bankimchandra Chatterjee, who was the first pioneer in the literary awakening which happened in Bengal…” Undoubtedly, it can be construed that Vande Mataram was the epicenter of that literary awakening.

It is a hymn of love for Motherland sublimated into an ecstatic devotion to the divine Mother–Bharat which is amplified as the trinity of Saraswati (the Goddess of knowledge and sanskriti), Lakshmi (the Goddess of wealth and beauty) and Durga (the goddess of strength and energy).

Bhupendranath Dutta, younger brother of Swami Vivekananda, wrote that according to the Maharashtrian priest at the Ramana Kali temple of Dhaka, the popular usage of Vande Mataram began when the Sanyasi rebel fighters used it as their battle cry. Vande Mataram or “Reverence to Mother” was not for the Goddess but the country.

How It All Began

Robert Clive gained the Diwani (right) of Bengal in August 1765 for the East India Company to collect taxes and execute civil justice after defeating Mir Kashim at Buxar in 1764. He used this Dwaita Shasan (Double Governance) to serve the Company’s interest as well as the Nawab of Murshidabad. He appointed Reza Khan as Naib Diwan of Subah Bengal. Reza Khan was the virtual ruler of Bengal with uncontrolled power from 1765 to 1770.

After Clive, Warren Hastings started to restrain Reza Khan by appointing company officers as district supervisors. Despite such obstacles, Reza Khan drastically increased taxes by 10 per cent neglecting economic hardship caused by previous years of drought and crippling the local economy.

Bands of warrior Sanyasis, essentially Dashnami Naga ascetics, mostly used to roam in Northern Bharat. Some of them became active in Bengal during early 1770’s and were even involved in the very complex succession struggle and imbroglio of Cooch Behar, then an independent State. In this process, the Sanyasis eventually found the British as their opponents. These Dashnami Sanyasis were traditionally entitled to collect debts and their share of collection by the Zamindars. Sanyasis as Gurus were entitled to Dakshina.

Due to enhanced taxation by Reza Khan, zamindars appealed to the company to foster their weakening exchequer. Instead of curtailing their own revenue demands, the company cancelled or re-adjusted their debts to the Sanyasis. The Company barred Sanyasis from collecting alms, Dakshina from landlords and farmers and from visiting certain pilgrimage sites, disrupting their traditional way of life. This led the ascetics to resort to armed resistance. David Neal Lorenzen, an eminent British-American historian and scholar of religious studies, concluded, “this led to animosity between the Sanyasis and the British.” The Bengali Hindus were oppressed first by Muslim invaders and subsequently by the British. Therefore, they were neither emotionally nor financially in a position to fight back. The sadhus gave direction and encouragement to the oppressed to fight against the oppressors. Sanyasis of the Naga, Giri, and Puri sects took the lead in the rebellion.

Birth Of the Song

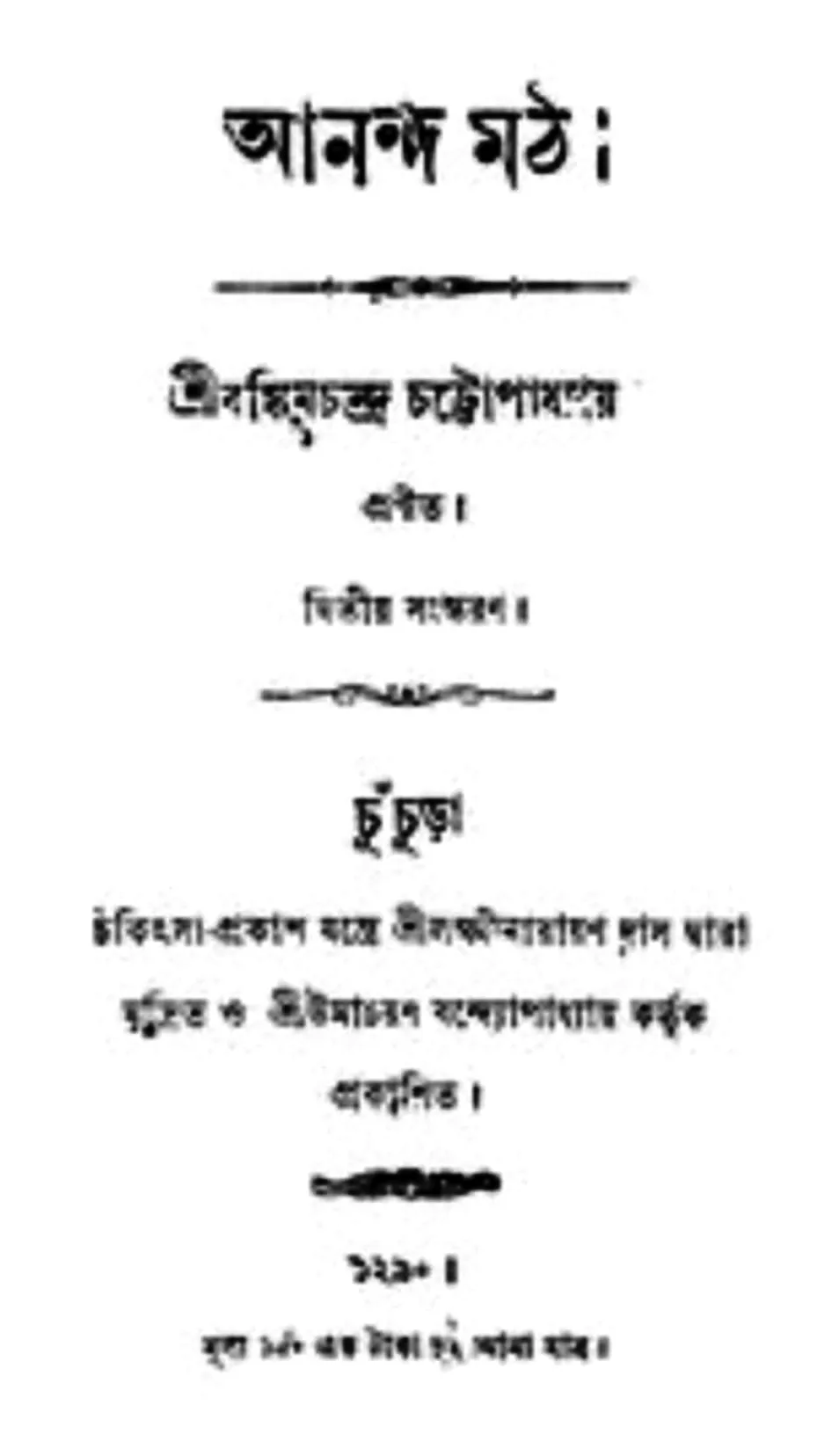

Bankimchandra had first written two stanzas of this song in 1876 as reverence to the Motherland highlighting her beauty and grandeur. The lyrics praise Bharat’s gorgeous landscape, fertile land, rivers and mountains hailing the country as a source of power and inspiration. He composed Vande Mataram at Chinsurah (Chuchura), in a white colour house of Adhya Family near Hooghly river (near Jora Ghat) in West Bengal.

Vande mataram…

Sujalam suphalam malayajashitalam …… Sukhadam varadam mataram…

Translated in prose by Sri Aurobindo, as : “I bow to thee, Mother. Richly-watered, richly-fruited, cool with the winds of the south, dark with the crops of the harvests, the Mother! Her nights rejoicing in the glory of the moonlight, her lands clothed beautifully with her trees in flowering bloom, sweet of laughter and speech, The Mother, giver of boons and bliss.” Bankimchandra added four more in 1881 for incorporating in his history based novel Anandamath which was published in 1882. He clarified that Anandamath was based on Sanyasi rebellion. The novel intensely narrates the Sanyasis’ armed fight against the Company’s troops led by Captain Thomas and Hay, Lieutenant Watson comprising mostly of ‘Tailangi Musalman,’ the foot soldiers from the Madras region who had accompanied Robert Clive on his transfer to Bengal. They were dubbed Nerhe in colloquial speech.

Dialogues in Anandamath precisely clarify that the Mother (Mataram) referred to the country, “As Mahendra said, this refers to the country. It’s not about any mother.” Bhavananda then explains that the land of birth is mother (janmabhoomi ie janani). On Mahendra’s insistence, Bhavananda sings the entire version wherein Goddess Durga and building her idols in temples are mentioned.

Vande Mataram and Swadeshi Movement

To the British imperialist the very utterance of that simple expression Vande Mataram became the proverbial red rag to the bull. The Lt. Governor of East Bengal had ordained that no one should utter that word; it was a ‘crime’. Thousands of young men had mocked that order and braved the British lathis and boots in the streets of Barisal by their thunderous roar of Vande Mataram. They had shed their blood and sanctfied that word into a potent and holy Rashtra-Mantra. It soon became the joyful and inspiring chant playing on the lips of the literate as well as the illiterate, the rich and the poor, the urban and the rural, the old and the young-in fact of one and all-men, women and children. Hundreds of revolutionary heroes ascended the gallows with that final obeisance to the Mother. Such an order was sent to the head-master of Kishoreganj High School on 18 January, 1906 – ‘ ….. to call upon boys of the first and second classes to copy out five hundred times: “It is foolish and rude to waste time in shouting Bande Mataram” and forward the manuscripts, all of which be nearly written with a certificate that each in the unaided work of the boy whose writing it purports to be” to the Inspector.

Even Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh founder and a patriot by birth Keshav Baliram Hedgewar in his student life couldn’t stay away from the fervour and propagation of Vande Mataram. In 1907, Keshav invited the wrath of his school management for making both section of his matric class singing Vande Mataram in front of a Government inspector in his school and was expelled from the school as a punishment for the same. This was against the tyrannical order called the Risley Circular which banned the public from chanting of Vande Mataram. However, no matter how diligent and careful the Government was to stop the propagation of Vande Mataram, in reality, its influence and propagation increased day by day. Police repression increased the popularity of Vande Mataram.

Vande Mataram was essential in Bharat’s quest for freedom. It was set to tune by Rabindranath in Raga Desh. He even sang it for the first time at the Congress session at Calcutta’s Beadon Square in 1896, thereby introducing it into the national consciousness. The song immediately acquired popularity and became an essential component of patriotic gatherings, marches, and rallies. Dakshina Charan Sen sang it five years later in 1901 at another session of the Congress at Calcutta. Poet Sarala Devi Chaudhurani sang the song in the Benares Congress Session in 1905. Lala Lajpat Rai started a journal called Vande Mataram from Lahore. Bipin Chandra Pal also started Bande Mataram, an influential English-language nationalist journal in 1906, that was subsequently edited by Sri Aurobindo, taking over the role from its founder. Hiralal Sen made Bharat’s first political film in 1905 which ended with the chant. Matangini Hazra’s last words as she was shot to death by the Crown police were Vande Mataram.

A book titled Kranti Geetanjali published by Arya Printing Press (Lahore) and Bharatiya Press (Dehradun) in 1929 contains first two stanzas of this lyrics on page 11 as Matra Vandana, and a ghazal (Vande Mataram) composed by Bismil was also given on its back on page 12.

When Bengal was partitioned, Vande Mataram became the battle song of the entire nation. On August 7, 1905 at the public meeting held at Town Hall in Kolkata, along with the call of boycotting foreign goods and announcement of Swadeshi Mantra, thousands of voices uttered the slogan Vande Mataram. The youth, inspired by patriotism, formed a group called Vande Mataram in October 1905. During the Swadeshi Movement, Vande Mataram became a significant symbol of resistance to British economic policy.

Rabindranath wrote, ‘When the rulers divided our country, and we struggled to establish the people’s will, it actually became popular as a national anthem during that struggle. Later, when Vande Mataram became a national slogan, we cannot forget the sacrifices made by many of our distinguished friends for it.’

Not only that, one of his songs written in the context of the Partition of Bengal reads,

Ek sutrey bandhiachhi sahasrati mon, Ek karje sonpiachhi sahasra jiban – Vande Mataram.

Aurobindo wrote, “It was thirty-two years ago that Bankim wrote his great song and few listened; but in a sudden moment of awakening from long delusions, the people of Bengal looked around for the truth and in a fated moment somebody sang Bande Mataram. The mantra had been given and in a single day, a whole people had been converted to the religion of patriotism. The Mother had revealed herself……” Leaders such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Aurobindo Ghosh promoted the usage of Vande Mataram as a unifying cry, and it quickly became associated with the spirit of Bharat’s freedom movement. Congress adopted it as National Anthem. To the British imperialist, the very utterance of that simple expression became the proverbial red rag to the bull. The Lt Governor of East Bengal had ordained that no one should utter that word; it was a ‘crime’. Thousands of young men had mocked that order and braved the British lathis and boots in the streets of Barisal by their thunderous roar of Vande Mataram. They had shed their blood and sanctified that word into a potent and holy Rashtra-Mantra. It soon became the joyful and inspiring chant playing on the lips of one and all. Hundreds of revolutionary heroes ascended the gallows with that final obeisance to the Mother. No matter how diligent and careful the government was to stop the propagation of Vande Mataram, its influence increased day by day. The police repression increased its popularity manifold.

Vande Mataram ‘Partitioned’

The British-Muslim axis felt that the formation of a permanent political body with the blessings of the British would yield them higher dividends in future. Accordingly, a conference of prominent Muslims was held at Dhaka under the leadership of Nawab Salimullah Khan – hailing from an Urdu speaking zamindar family with extensive land holdings and All India Muslim league was officially formed on December 30, 1906. Salimullah was the proponent of the British. The Muslim league endorsed Curzon’s partition of Bengal. The Lal Istahar or Red Pamphlet distributed to the delegate on that occasion carried several anti-Hindu appeals. Outrageous statements in the Red Pamphlet provided fuel to the fanatic fire of Muslims. Very soon on March 4, 1907, riots broke out in Comilla (now in Bangladesh) incited by the henchmen of Salimullah resulting into assault, murder, looting, rape, destruction of properties and arsoning in full fury. As a sequel of such events, an alarming incident has been mentioned in Rezaul Karim’s essay Bonfire of Anandamath. It states, “In the capital city of Calcutta at a large congregation Muslim leaguer Mussalmans made a bonfire of Bankimchandra’s Anandamath. The civilised world was appalled by this horrible event that even tarnished the barbaric bigotry of the middle-ages.”

But Abdul Rasul, a barrister, sang Vande Mataram while presiding over the Bengal provincial conference in 1906. Nobody had anticipated the danger of this bonfire as envisaged through Heinrich Heine’s foretelling, “those who burn books will in the end burn people”.

Hindus observed it soon during ‘The genocide in Noakhali’ and ‘ The great Calcutta killings’. Undoubtedly, Anandamath was usually inspirational for Hindus. A religion not a single word was mentioned against Islam. The narrated battles were against the British with mostly ‘Tailangi Musalman’ foot soldiers. In the process certain colloquial slang expression have been used, as is common in any live dialogue. This above view of Rezaul Karim is also endorsed by Dr Ahmed Sharif, Chancellor of Dhaka University when he rightly says in his book, Pratyay O Pratyasha – “The Muslims that Bankim abused were the Turkey Mughal rulers. It is natural and proper to be hostile to the foreigners and infidels who settled in this country and took away the freedom and wealth of the countrymen.”

The Khilafat movement raged in Bharat during 1920-22. Congress actively participated, linking it to Swaraj. During this period, leaders like the Ali brothers – Mohammad and Shaukat, Abul Kalam Azad, Dr Ansari and Hakim Ajmal Khan were accustomed to stand respectfully on the dais during the singing of Vande Mataram. They never opposed it. But the attitude of Ali brothers was radically changed when the Khilafat chapter was over with the removal of Khalifa by Kamal Ataturk, arrest of Mohammad Ali and Gandhiji’s withdrawal of the non-cooperation movement as a sequel to the Chauri Chaura happenings.

It was at the Kakinada session of Congress in 1923, that the first blow was struck at National Anthem. Mohammad Ali, himself a Maulana, objected to the singing of Vande Mataram by Pandit Paluskar at the opening session. Mohammad Ali presided over that session. His specious logic was that Islam forbids singing and music is taboo in Islam. Paluskar, however, stuck to his post. In a voice of righteous indignation, he retorted to the Maulana, “The Indian National Congress is neither the monopoly of any one particular religious sect nor is this place a mosque, where singing could be prohibited. You have therefore no authority to prevent me from singing ‘Vande Mataram’. Moreover, if singing in this place is against your particular religion, how is it that you could tolerate music in your presidential procession?”

The Maulana, of course, had no answer to this challenging question, and left the dais. Vande Mataram was proving an ‘irritation’ to the Congress in the path of winning over the Muslims. Congress, as we know, had remained unruffled even in the face of banning of Vande Mataram by the British. It had, after passing through that fire, even adopted it as its national anthem. But now in the face of Muslim opposition, it began to be caught in a dilemma. In 1922, it had already adopted Mohammad Iqbal’s Tarana-e-Hind (The Song of Hindustan) “Saare jahan se achha Hindustan hamara… (our Hindustan is the best in the entire world) as the associate national anthem just to satisfy the Muslims. But this was just a passing phase in the poetic outpourings of Iqbal. After his return from Germany, where he had delved deep into Islamic studies, Islam and Pan-Islamism became the dominant note of his thought and poetry. He now wrote the poem Tarana-e-Milli (Anthem of Muslim Ummah) comprising the line, Muslim hain ham watan hai, sara jahan hamara (We are Muslims and the whole world is our land).

The real test for Congress came in 1937, when elections to the Provincial Assemblies were held and the Congress was returned to power in seven provinces. The Congress Governments, in line with the past Congress tradition, began commencing the Assembly proceedings with Vande Mataram. The Muslim League, equally true to its tradition, declared a war against it. The League members in the Assembly raised a storm of protest and staged walk-outs. The Congress Working Committee was scheduled to meet in October 1937 at Calcutta. The Muslim League conducted its session earlier and denounced the Congress-ruled States as ‘Hindu States’. And the most weighty testimony it adduced was the singing of Vande Mataram in the Assemblies.

Jinnah in the meanwhile had repeatedly sought its abandonment. The League termed it as callous, anti-Islamic, idolatrous in the inspiration and ideas, and subversive of the growth of genuine patriotism in Bharat. The League called upon Muslim members of various legislatures and public bodies in the country to not associate themselves in any manner with this highly objectionable song. Congress thought, if Hindu-Muslim unity, without which the British would not part with power was to be achieved, the Muslims should not at any cost be displeased. Accordingly, Congress appointed a committee comprising Nehru, Subhash Bose, Azad and Narendra Dev to study the song and recommended to cut out those portions of Vande Mataram which were likely to offend the Muslim susceptibilities as indicated in the League’s resolution. Only the first two stanzas of the song depicting a physical picture of the motherland were retained and the subsequent stanzas that had the real essence of the spirit of patriotism were dropped.

The committee also recommended that singing Vande Mataram not be made mandatory and Congress further gave its organisers ‘freedom to sing any other song of an unobjectionable character in addition to, or in place of Vande Mataram’. This clearly indicated that Congress had taken away the position of Vande Mataram as National Anthem and placed it on par with other national songs.

Even Gandhiji at Comilla, in 1927, said that the song held up before one’s mind the picture of the whole of Bharat – one and indivisible. In 1939, the same Gandhiji wrote, “If at any mixed gathering, any person objects to the singing of Vande Mataram even with Congress expurgations, the singing should be dropped.” (The Harijan)

Legal Status and Recognition

On January 24, 1950, the Constituent Assembly of Bharat adopted Vande Mataram as the Republic’s national song. Rajendra Prasad, who was presiding the Constituent Assembly, made the following statement which was also adopted as the final decision on the issue: “… The composition consisting of the words and music known as Jana Gana Mana is the National Anthem of India, subject to such alterations in the words as the Government may authorise as occasion arises; and the song Vande Mataram, which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it. (Applause).”

— Constituent Assembly of India, Vol. XII, 24-1-1950.

While the Constitution of India does not make reference to a “national song”, the Government filed an affidavit at the Delhi High Court in November 2022 stating that Jana Gana Mana and Vande Mataram would “stand on the same level”, and that citizens should show equal respect to both. (The Times of India, November 7, 2022. Retrieved November 7, 2022)

An appeal to the Nation

It is regrettable that youth has been accustomed to utter Vande Mataram at par with Maa tujhe Salaam following A R Rahman’s composition. We should not forget that even Gandhiji, in a speech given in Guwahati (Assam), urged that “Jai Hind should not replace Vande-mataram”. He reminded everyone present that Vande Mataram was being sung since the inception of the Congress. (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, January 10, 1946, page 212). Similarly, Maa tujhe Salaam should not replace Vande Mataram. Because it is not merely a greeting or a salutation, it is a Mantra.

Comments