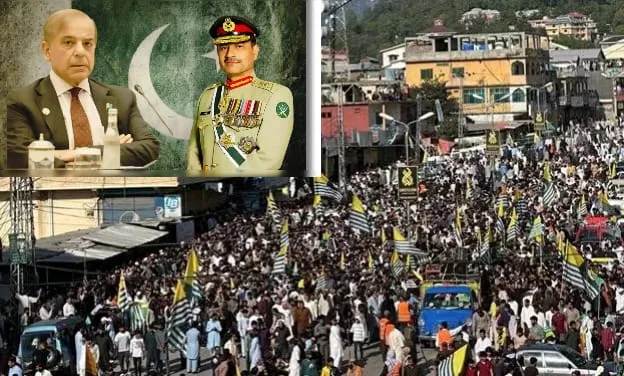

The Gen Z movement that shook Bangladesh and Nepal is now shaking Pakistan-occupied Jammu & Kashmir (PoJK). Students who were earlier quiet spectators have poured onto the streets, continuing a chain reaction of public anger that began weeks ago and shows no sign of subsiding. What started as a campus-level grievance over rising fees and flawed assessments has evolved into a serious political headache for Islamabad. Pakistan’s government now finds itself dealing with a restless, angry, digitally connected generation that refuses to be silenced. The first sparks of discontent had appeared long before the student protests. Weeks earlier, the Awami Action Committee (AAC) led a massive popular uprising in Muzaffarabad, Poonch, Kotli and other parts of PoJK. Slogans of “Azadi”, this time not from India, but from Pakistan, echoed across the region. Protesters openly questioned Pakistan’s occupation, demanding either full independence or, in some cases, accession to India. What Islamabad calls “Azad Kashmir” witnessed violent clashes, blockades and days of street battles. It eventually ended only after the Shahbaz Sharif government was forced to negotiate, agreeing to several major demands relating to electricity, taxation and civic services. But even as the government claimed victory, another confrontation began brewing.

Botched E-Marking, Fee Hikes and Broken Promises Push Students to the Streets

Soon after the AAC protests calmed, students of the University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir in Muzaffarabad launched demonstrations against fee hikes, inadequate facilities and poor quality of education. The administration responded by banning all political activity on campus, a move that only strengthened the agitation. Tensions escalated as students accused the university of charging exorbitant amounts, sometimes lakhs of rupees every few months, without offering facilities even comparable to ordinary Pakistani colleges. A similar protest had erupted in January 2024, during which teachers and other government employees joined students, demanding long-pending salary hikes and financial dues. This time, the anger spread much faster. High school and intermediate students also joined the protests. The turning point came when the government introduced e-marking, a digital evaluation system, for matriculation and intermediate examinations. Students argued that the system was hastily implemented, untested and filled with technical gaps.

1/4 GenZ Protests in #Pakistan Occupied #Kashmir

Students & Gen Z in PoK and Pakistan are protesting fee hikes, unfair policies, #Unemployment & governance failures

From Muzaffarabad to Mirpur, call for PoK to join #India #spoilthevote #GenZProtest #sstvi #POK #BabarAzam pic.twitter.com/inrNtv8tPe

— The Wonk (@thewonkin) November 5, 2025

On October 30, the Intermediate First-Year results were finally declared after a six-month delay. Instead of relief, the result triggered outrage. Thousands of students complained that they had received marks far below expectation. Some who wrote well failed; others who barely attempted the exam were shown as passed in subjects they did not even write. The entire credibility of the education system came under suspicion. Local reports say the Mirpur education board has formed a committee to review the e-marking process, but the government has not issued a clear explanation. Meanwhile, students are demanding that re-evaluation be free of cost and conducted manually. The issue is no longer limited to education alone. Young people are openly speaking about collapsing infrastructure, poor healthcare facilities, failing public transport, unemployment and government apathy. What began inside classrooms has now spilled onto the streets. Unconfirmed reports claim that police opened fire in some towns, injuring several students. Videos of baton-charging and arrests have been widely circulated. Islamabad, however, blames India, a routine response whenever unrest breaks out in PoJK. Instead of addressing grievances, the government has directed security agencies to suppress the movement.

From military crackdown to terror networks: The dark reality of PoJK

According to multiple Pakistani media discussions, Army Chief Asim Munir and the ISI want to stamp out the protest before it spreads nationwide. Islamabad plans to introduce the 27th Constitutional Amendment, which grants greater powers to the army and intelligence agencies. Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) leader Bilawal Bhutto Zardari revealed that the government had approached his party for support. The amendment is widely viewed as a move to strengthen the military’s grip and formalise Munir’s authority. After India conducted “Operation Sindoor” in May, the Pakistani establishment elevated Asim Munir to the rank of field marshal. Now, he has also been tasked with “managing” the situation in PoJK. Yet, the army’s presence has only deepened resentment among youth, who now see the military as the face of repression.

PoJK’s picturesque landscapes, snow-capped mountains, pine forests, apple orchards and shimmering lakes, are identical to the Kashmir within India. Tourists often assume the region is peaceful. But underneath this scenic beauty lies anger, exploitation and decades of destruction. For locals, PoJK is not “heaven”; it is a prison controlled by Islamabad and the army. Dissidents abroad claim Pakistan has turned PoJK into a global terror factory. In the 1990s, more than a thousand terror training camps were openly run in the region. Lashkar-e-Taiba alone operated hundreds, often linked with local madrasas for religious indoctrination. Young boys were given training, funded by the Pakistani state, and pushed across the LoC into India. The aim was simple that wage a covert war against India through militancy. But the strategy backfired. Today, Pakistan’s economy has collapsed and India has tightened its border security. Cross-border infiltration has dropped sharply and terrorist activity is no longer easy to execute. The “terror factory” has been forced to shrink.

The situation is even more complex. PoJK hosts not only anti-India terror groups but also Taliban factions, Al-Qaeda elements, ISIS-inspired networks, Shia extremist outfits and even Boko Haram operatives. Over the years, these groups have become threats to Pakistan itself. Muzaffarabad, PoJK’s capital, has long been infamous as a hub for printing and smuggling counterfeit Indian currency. There was a time when locals joked, “Give a Gandhi, get a Jinnah.” Notes printed in PoJK were smuggled into India via Nepal in massive quantities, destabilising India’s economy.

The generational revolt that could break Pakistan’s hold on PoJK

The situation in PoJK highlights the contrasting paths of India and Pakistan. India has spent years trying to remove terrorism from J&K and push the region towards development. Today, even critics acknowledge that New Delhi is investing crores of rupees in roads, schools, tourism, electricity and digital services. While problems remain, Kashmir is no longer the valley of militancy that it was in the 1990s. Pakistan, in contrast, has ignored PoJK entirely. Islamabad used the region as a launching pad for terror groups. Dictators like Zia-ul-Haq openly encouraged radicalisation. Foreign journalists have repeatedly reported that PoJK was handed over to the ISI and military generals, not civilian administrators. In the 1990s, PoJK hosted vast training camps for Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed fighters. Ajmal Kasab, the gunman involved in the 26/11 Mumbai attack, was trained in Muzaffarabad. He was recruited from poverty, promised money and glory, indoctrinated and turned into a suicide fighter. Thousands of boys met the same fate, used, radicalised and thrown away.

Now, Pakistan is paying the price. Taliban fighters have returned with power. Al-Qaeda-linked groups have regrouped. ISIS cells have emerged. Shia-Sunni militant clashes are increasing. The monsters created to fight India are now turning against Pakistan. For decades, many in PoJK believed Pakistani propaganda. But today, internet access, smartphones and global exposure have changed everything. Educated youth are realising that Islamabad treated them as expendable pawns. There is no development, no healthcare, no jobs, no democracy, no freedom. Students now say openly: “Pakistan used us for terrorism, not for nation-building.” Activists abroad are even harsher, “Pakistan turned our homeland into a terror factory.” This is why the Gen Z movement is not just about marksheets or fees. It is a rebellion against decades of exploitation and lies.

Pakistan’s deepest fear is not riots or protests, it is the possibility that India might see this as an opportunity. Islamabad knows that if unrest grows, if slogans for freedom intensify, and if the public openly demands integration with India, Pakistan will lose its grip over PoJK forever. For the first time in decades, anti-Pakistan sentiment in PoJK is not driven by militants, it is driven by students, educated, connected, aware of global politics, unafraid of police and army intimidation. If this movement grows, the demand for liberation will not remain symbolic. And the world will finally see what PoK has been suffering for years. Whether the Shahbaz-Munir establishment controls this fire or is consumed by it will define the future of PoJK.

Comments